Applying for refugee status in Japan is a strenuous and lengthy procedure, requiring asylum seekers to remember and report details of life-threatening experiences they’d had fleeing from their home country.

The Japanese Immigration system is particularly strict and inflexible, denying their personal statements and demanding physical proof of persecution which asylum seekers, prioritizing fleeing for their lives, do not bring with them either for safety reasons (e.g. proof of participating in anti-government groups), for lack of time to prepare, or merely because there is little to no proof. Although the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) is regularly reforming immigration procedures concerning refugees due to international pressure and now the COVID-19 pandemic, this page presents the general statuses asylum seekers are and can be under in Japan, giving special attention to those with Karihoumen status – living under detention conditions, despite being outside of the detention center.

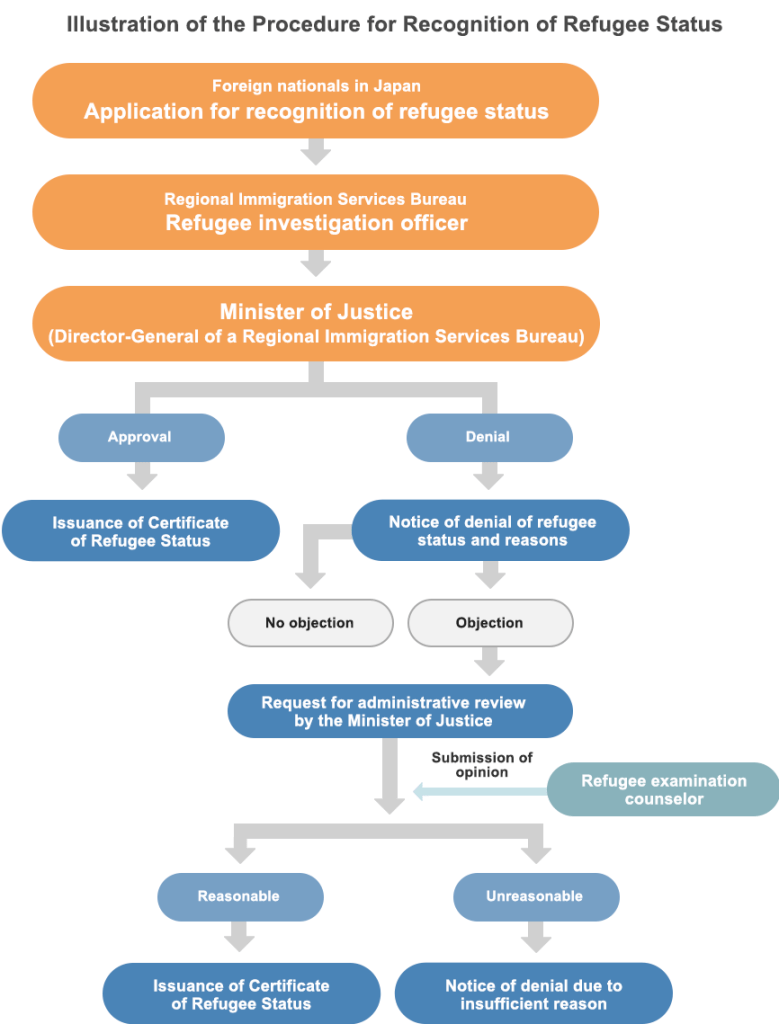

According to the Immigration Services Agency of Japan, the refugee application procedure consists of mainly three parts: the document application, interview(s), and if rejected – which around 99% of the applicants are – a judicial appeal. The documents necessary for applying are the following:

- Application form

- Personal statement in Japanese

- Other proof that one is a refugee in Japanese

- 2 photos

One of the biggest thresholds faced by refugee applicants in Japan is the language barrier. In contrast to what might be expected, immigration officers, interviewers, and application reviewers do not speak English. Applicants have no choice but to find a way to translate all their documents into Japanese, which is most of the time financially inaccessible to them. Additionally, they generally do not have the network to find native speakers capable of official translation in a country where they can only communicate with a handful of people. In theory, the basis of judging an applicant for refugee recognition is the legitimacy of their statement of persecution. The 1951 Refugee Convention, signed by Japan in 1981, stipulates a refugee to be a person who,

“…owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” (Article 1A (2)) (Emphasis added by JAR).

In addition to not speaking a common language with applicants, interviewers who make the decision on whether or not to grant refugee status do not have a background in refugee nor international law. In the Japanese immigration system, employees do not specialize in an area but rotate among various departments. With their lack of specialized knowledge and subsequent inability to properly judge applications, decisions end up being based on the scrupulosity of the application, such as inconsistencies of speech in the personal statement – for instance, stating one was violated on “date A” in one interview and then saying “date B” in the next. During interviews, asylum seekers must remember and recount physical torture, rape, and war, among other painful experiences. They attempt to memorize their personal statements by heart, but details such as dates, names, and times inevitably become blurry. Although these kinds of details do not change their reason for fleeing, Japanese immigration denies many applications with such justifications.

Status Possibilities in Japan

- Refugee Status

This is the ultimate goal. Being able to live like any other citizen in Japan, legally welcomed and feeling safe. The individuals that receive such “luxury” are granted:

- Protection against deportation

- Status of residence

- Right to travel

- Equivalent rights of Japanese citizens living in Japan including healthcare, education services, employment and social welfare.

Note: Consideration of Humanitarian grounds

This status acts as an appeal after being rejected, on humanitarian grounds. This appeal is meant for and used by applicants with family in Japan or applicants who are ill. Immigration reviews past records, family links, and the situation in the country of origin. If accepted, one receives special permission to stay in the country, or permission to change their status of residence.

- Designated Activities

The status held by most asylum seekers in Japan, the Designated Activities visa allows for those to whom it is granted to apply for a work permit after nine months. However, they live without health insurance and cannot sign their own housing contract. Furthermore, this visa must be renewed every six months at one’s closest immigration office once the first nine months have passed. Before that, the visa must be renewed every three months.

- Karihoumen

Different from other nations committed to the UN Refugee Convention, Japanese Immigration has a status called Karihoumen, which translates to Provisional Release. As suggested by the name, this status gives permission to asylum seekers to temporarily stay outside of the detention center. It was introduced to the Law on Refugee Recognition in 2004 and is the status most of the narrators from this research hold. Almost unanimously, these asylum seekers express the injustice and inhumanity of the system – seen as detention outside of the detention center. Despite not being closed within concrete walls, those with Karihoumen status have no work permit, no health insurance, cannot own their own housing, and can only leave the prefecture they live in with special permission from the nearest city hall. Moreover, this status must be renewed every two months and its renewal can be rejected at any time if the immigration officials deem it necessary. According to IMMI, “when granting provisional release, the director of the immigration center or the supervising immigration inspector will collect the guarantee deposits of up to 3 million yen, set conditions on residence and activities, and require the detainee to visit the immigration office if he finds it necessary to do so.”