The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, commonly referred to as the Refugee Convention, is an international legal document aimed at protecting refugees. It was created by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1951 and signed by Japan in 1982.

The document defined a refugee as, “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” The core principle is non-refoulement, meaning a refugee should not be returned to a country where they would face serious threats to their life or freedom, and to protect the refugees already in one’s country.

Despite being commonly used interchangeably, asylum seeker has a different meaning from refugee. An asylum seeker is a person who is “seeking protection of a state and has not yet been granted refugee status. That is, has not received the aid he/she flees for.”

Global Statistics

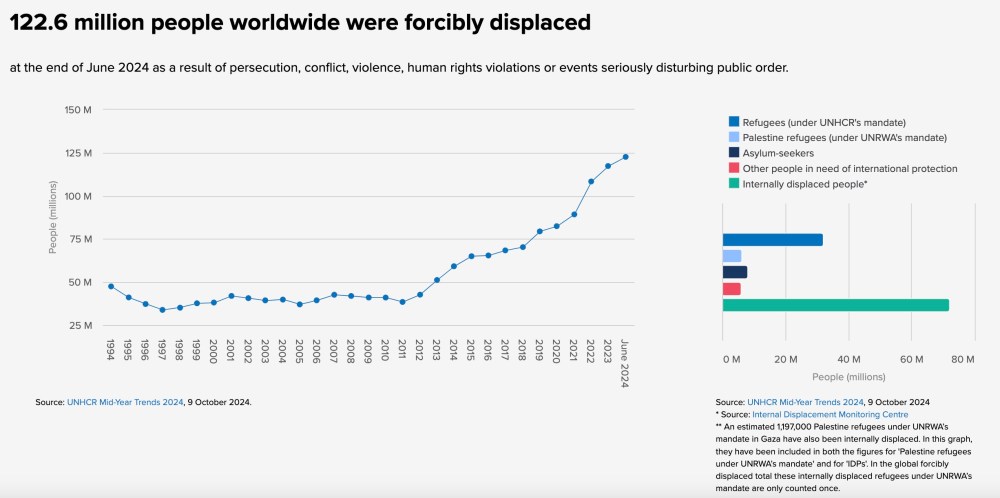

The number of forcibly displaced people has peaked in the past thirty years, with 122.6 million people having been forcibly displaced at the end of June 2024 for various reasons such as persecution, violence, and state conflicts. Out of the 122.6 million, 32 million are recognized as refugees while 8 million are asylum seekers. The majority of the people, 72.1 million, are internally displaced people, or in other words, are dislocated and forced out of their homes within their home country. Of all forcibly displaced people, about 40 percent are children under the age of 18 years old. 71% of the refugees in the world are being hosted in low- and middle-income countries.

Top Refugee Origin Countries and Host Countries

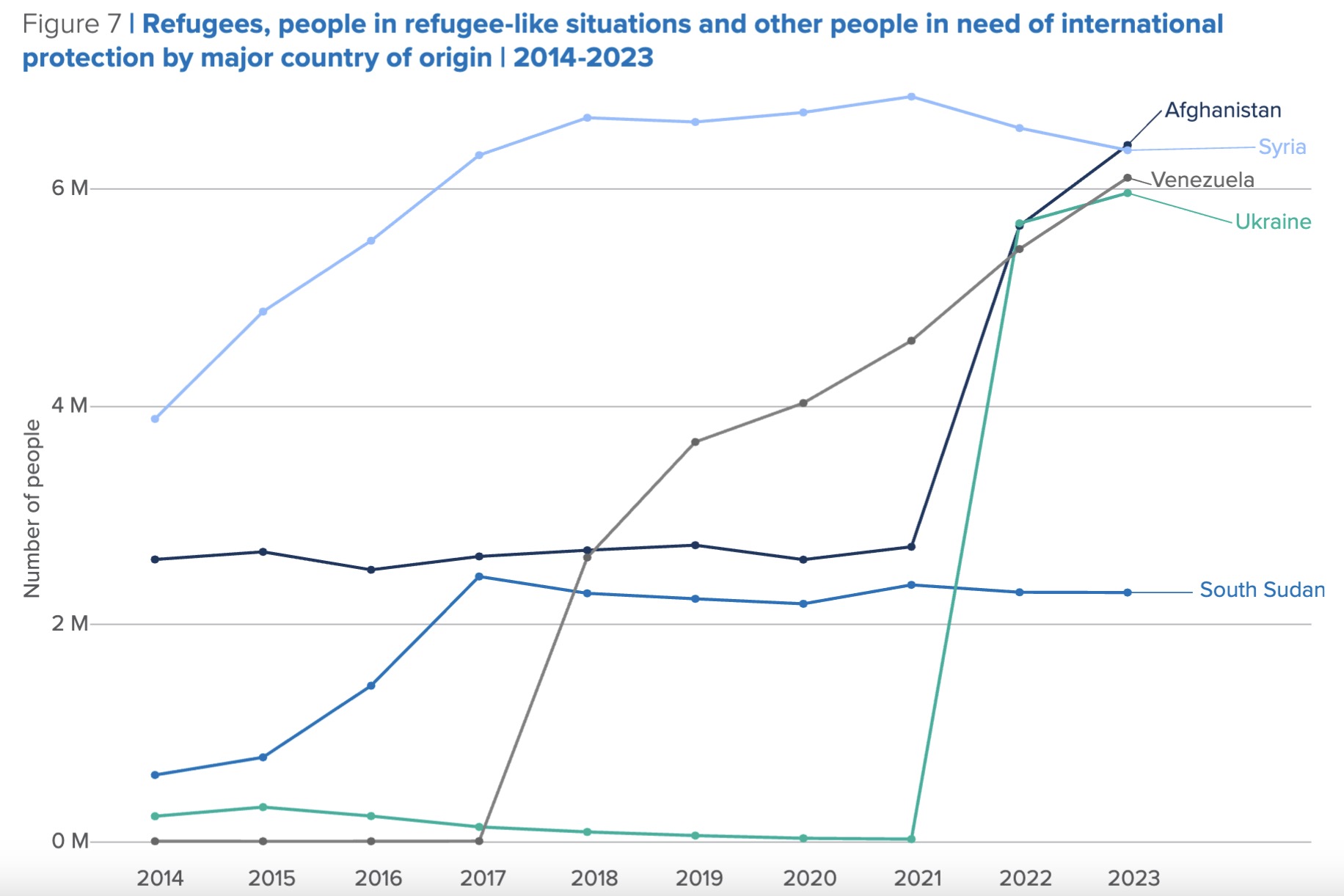

This 2023 graph from UNHCR displays the data for the top five countries where refugees originated or fled from (their home countries): Afghanistan, Syria, Venezuela, Ukraine, and South Sudan. These five countries represent three in four (73%) of the world’s refugee population.

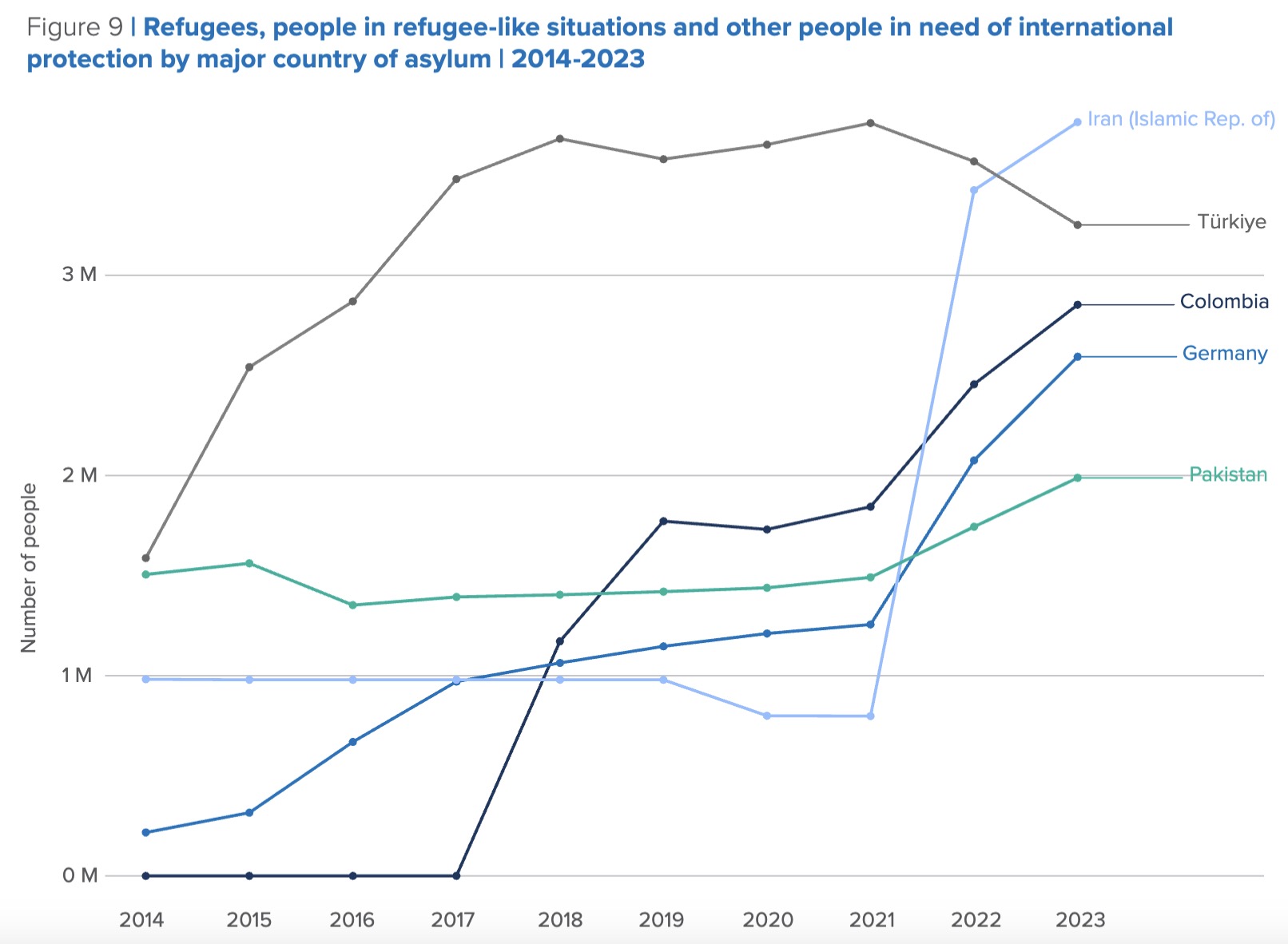

The following graph, also from UNHCR, displays the top five countries that refugees fled to (the host countries) in 2023: Iran, Türkiye, Colombia, Germany, and Pakistan. We can see that the top host countries are low- and middle-income countries.

Japanese National Statistics

Japan has a long history of accepting refugees compared to the current numbers but constantly struggles with accepting refugees when compared to rates of acceptance in other developed countries. Between 1978 and 2005, specifically, post-Vietnam War, Japan accepted over 10,000 Indochinese refugees mainly from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The late 1970s marked a significant shift in Japan’s immigration policies, in light of how Japan had been unwilling to receive foreigners for resettlement previously, but started to do so with refugees. This shift led Japan to join the international agreement regarding refugees in 1981, signing the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention in 1982 and thus agreeing to the protocols of the convention, resulting in the update of the country’s Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act. The Immigration Services Agency under the Ministry of Justice was and still is assigned the duties of refugee recognition. However, initially, this office focused only on illegal immigrants and those who overstayed their visas. Due to this preceding perspective being a strict emphasis on immigration control, the Agency’s ability to properly approach the new duty of recognizing refugees was negatively affected.

In 2008, Japan decided to start a resettlement program and subsequently joined the UN’s resettlement program in 2010. By doing this, the Japanese government pledged to accept 90 refugees from Myanmar over the course of three years. According to the report by the UN Refugee Agency, Japan continues to recognize asylum seekers from Myanmar as refugees at a significantly higher rate than those from other countries, which may be attributable to its deep history of friendship with Myanmar.

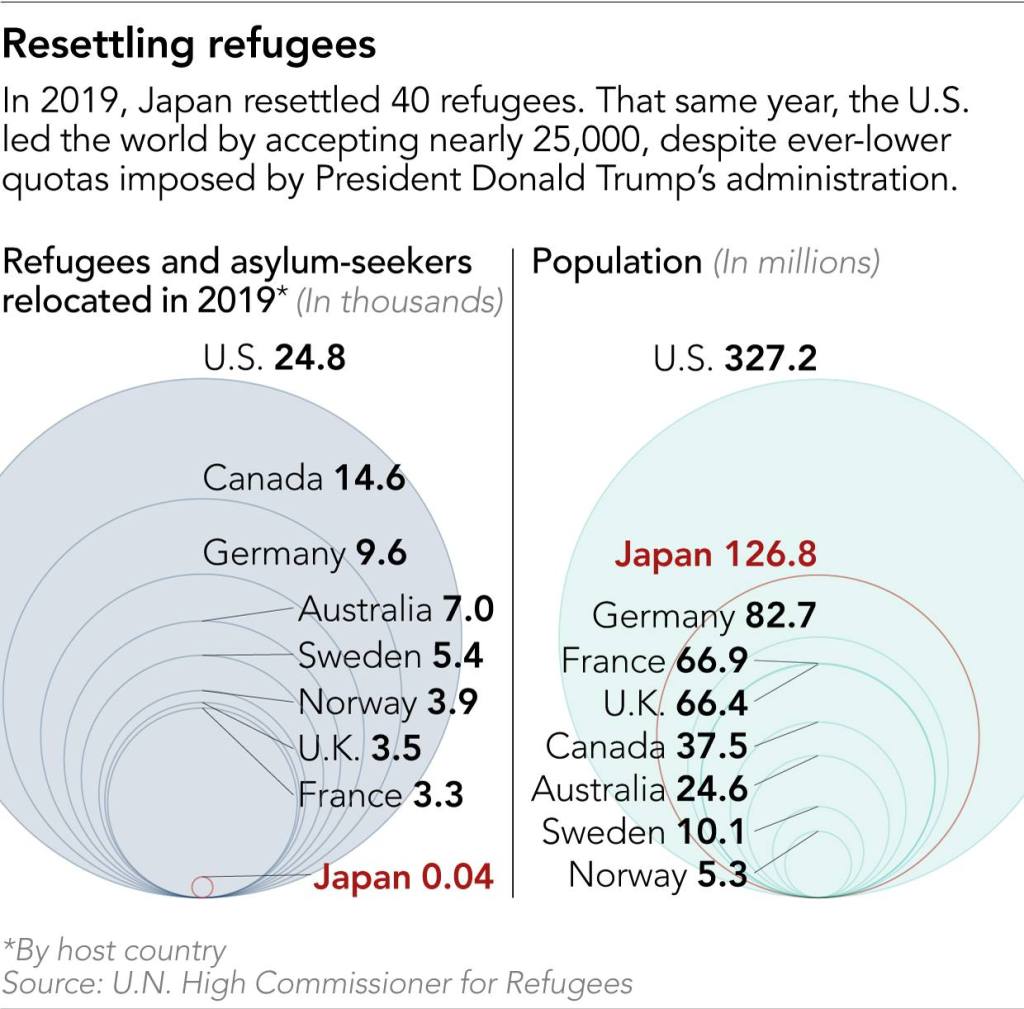

By joining the international agreement, Japan committed to accepting asylum seekers and granting them refugee status. However, from the beginning the country presented strict immigration regulations, causing the number of asylum seekers accepted as refugees to be indisputably low. According to the Immigration Services Agency of Japan, the number of applicants who were granted refugee status in 2024 was 176, or about 3.33% of the 5,293 applications reviewed. The top five countries applicants were coming from were Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey, India, and Pakistan (in order of most applied). About 5.42% had been accepted in 2023, with refugee status granted to 289 out of 5,334 applications reviewed. In 2022, the acceptance rate was 3.34%, only granted to 187 out of 5,605 applications reviewed. The figure below displays a comparison between the number of accepted refugees and the population of Japan and other developed countries in 2019, where we can visually see Japan’s low acceptance rate.

Role of Japan as a Developed Country: Theory vs. Practice

In theory, Japan has a humanitarian obligation due to the signing and ratification of the 1951 Refugee Convention in 1981, which states that each country involved must do its part in “sharing the refugee burden” and protecting them. Japan is not only committed to an international agreement, but the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) also asserts Japan’s position on refugee assistance. MOFA’s homepage states: “From a humanitarian point of view, refugee assistance is a bounden duty of a member of the international community.” Despite these agreements and statements, in practice, Japan accepts an extremely low number of refugees, in recent years below even one percent of the total applicants.

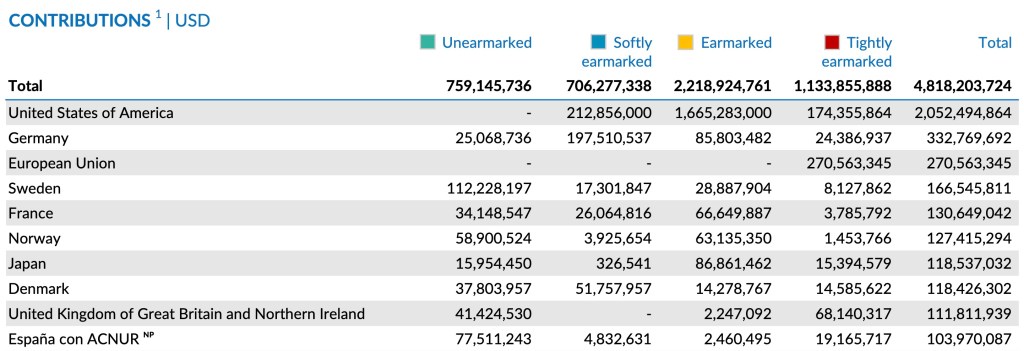

One justification Japan gives for its low acceptance rates is that the UN Refugee Convention does not clearly state a target number for accepting refugees. Each country may create its own laws and targets. Therefore, Japan claims to “share the burden” through its financial contributions to the UNHCR. The Japanese government has been amongst the top donors for the past fifteen years. The image below shows Japan being the seventh-largest donor to the UNHCR in 2024, donating a total of 118,537,032 US dollars. It has gone down from the fourth-largest donor the previous year.

Another common justification is the presence of fake refugee applicants. A fake refugee is defined as an individual who takes advantage of the benefits of the refugee status, mostly the work permit. In other words, these individuals posing as fake refugees are not refugees but pretend to be in order to exploit the system, resulting in Japan tightening their system of screening refugees in order to weed out the ones that can be perceived as ‘fake’. This strict system requires refugees to give evidence through actual materials and documentation of how they came to be refugees.

One example of this commonly held perception of the prevalence of fake refugees is seen in an artist’s modification of the photo below of a refugee child into a critical animation. The photo below shows a six-year-old Syrian girl in a refugee camp located in Lebanon. The photographer, Jonathan Hyams, was a worker for the organization Save the Children.

In September 2015, right-wing Japanese artist Toshiko Hasumi modified this photo into the cartoon shown below with captions that translate to: “I want to live a safe and clean life, eat gourmet food, go out, wear pretty things, and live a luxuriously, all at the expense of someone else. I have an idea. I’ll become a refugee.” This cartoon caused backlash and stirred discussion about xenophobia and racism in the world. In Japan, there is a common perception of refugees, or even foreigners in general, as being dangerous, too different, scary, lazy, or criminal. This fear of foreigners has had a negative effect on refugees and asylum seekers when they resettle in Japan. Additionally, these stereotypes give credence to and strengthen the myth of the fake refugee in Japan.

The artist’s goal was to bring attention to fake refugees and deny the plight of actual refugees, so she did not apologize for her art. The prevalence of this misconception is widely held by the Japanese populace and directly affects the public’s ability to be open to accepting more refugees. So despite already having fled for their lives, searching and hoping for a chance at a fresh start, asylum seekers arriving in Japan are met with new difficulties in both realms of legal acceptance and social integration.

In conclusion, despite Japan having been one of UNHCR’s top financial contributors, the country does not give much attention or financial support to the asylum seekers and refugees within Japan. Many of those who seek asylum are made to suffer through the strict screening process that is built to deny them, providing documents and evidence of their status as refugees when realistically, these people were fleeing for their lives, thinking only of how to get themselves and their families to safety and not of proving their plight through documentation.