Introduction

Though the stories presented on this webpage may seem clear-cut and polished, compiling the final product is no small feat. Every semester, the Digital Oral Narratives class taught by Professor David Slater at Sophia University assembles a new group of eager students who will contribute to this project over the next few months. Several teaching assistants (TAs) support the project both in class and editing on the website. On this methodology page, we would like to outline the entire process from top to bottom regarding everything from the preliminary theory readings students complete, to how Professor Slater selects narrators, to how the data is analyzed and written up. With this look into the methodology of the Refugee Voices Japan project, we hope to appreciate the extensive process that students go through in order to best present the life stories of the refugees we talk to.

“When it came to refugees, I didn’t have any cultural familiarity with the narrators…I’m always interested in what’s going on in other countries, but it presented a challenge.”

Ayano, 2021

Background Readings

In order to give students, who are at different levels of knowledge and engagement, a grounded basis in forced migration studies, a selection of readings are analyzed in the first few weeks of the course. The most central document to the Digital Oral Narratives course is the 1951 Refugee Convention. The document is integral to our refugee studies as it lays out the founding legal definitions used by the Japanese government in their migration laws since its ratification in 1981. The 1951 Refugee Convention and the subsequent 1967 Protocol define a refugee as:

“As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

These definitions are important because they narrow the scope of who can be considered who is a refugee, and therefore what rights are granted when entering another country. The host country will give different provisions to those deemed a ‘refugee’ and those deemed something else (e.g. asylum seeker, economic migrant, or illegal immigrant).

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh’s Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies is used as one of the foundational theory readings for the class. It goes over the 1951 Refugee Convention definitions as well as the historical context of World War II which led to its creation. The introduction of this text also walks students through the expanding field of refugee studies and how the socio-political events occurring worldwide shape the patterns seen in migration. In particular, the chapter “The International Law of Refugee Protection” by Goodwin-Gill expands on the policies stipulated in international law that are used to protect refugees.

“Non-refoulement” is a key term that students study, which essentially means that refugees cannot be forced to return to the countries in which they were facing persecution. This non-refoulement policy is a central pillar of international law regarding refugees, one that the 1951 Convention must abide by. Once students have a firm grasp on this basic, foundational information surrounding refugee international law, they can better understand specifically why Japan’s refugee policy is shaped the way it is.

Japan accepted 47 out of 3,936 refugee status applicants in 2020. On average, the country accepts about 0.3% of its annual refugee applications. This becomes especially significant when compared to other countries such as Germany which accepted about 74% of their applicants, about 55,388 in 2020. Japan’s refugee policy is outlined in the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act of 1981. As the Immigration Services Agency of Japan processes these applications, oftentimes control over who is entering the country is prioritized over the protection of those who have already entered. Japan has ensured that the definition of a refugee remains narrow and difficult to attain by enforcing a policy that stipulates that one must be personally targeted by their government in order to get refugee status recognition. This systematically excludes many legitimate refugee applicant claims, as it is extremely difficult to meet the requirements. For more information on the Japanese immigration system, please click here.

Beyond this, we usually gather contemporary newspaper articles on the way that refugees are represented in the Japanese media. This helps us target our presentation of findings on the final website.

As we work with refugees in Japan, students must also thoroughly understand the ethical concerns when interviewing them. Clark-Kazak’s “Ethical Considerations: Research with People in Situations of Forced Migration” outlines the key points that researchers should keep in mind throughout their research process. Refugees find themselves in vulnerable places where they are often at the mercy of those around them. They may be dependent on the money or even the possibility of assistance that researchers may be able to provide. This dependence fosters an unbalanced power relationship which must always be acknowledged and remedied. Giving refugees agency over their personal data and how it is to be used is how this project seeks to address this issue.

Selecting Narrators

The selection process of narrators is carried out through the network cultivated through the support activities of Sophia Refugee Support Group (SRSG). This school club conducts various activities such as social events for refugees, donation drives, and advocacy activities which has resulted in an extensive network of connections in the refugee community. When reaching out to possible narrators, it is important to take into account the types of people who would be best to interview. Not every refugee applicant wants to go public with their story, but many others are very keen to find a platform to let the world know what is going on. Looking for people who have the patience and motivation to work with and teach young people about extremely complex and emotional events is a key part of the process. Part of this is also finding those who are willing and able to reveal their feelings, their experience, and world views in a public way.

Analyzing Existing Transcripts

Many narrators we work with have previously done interviews as part of the project. Once students are introduced to the semester’s narrators they are provided with video footage and transcripts of these old interviews. Since each interview is on average 1.5-2 hours the transcripts tend to be about 60-80 pages in length. This preliminary look at the narrators helps students gain a feel for the person, as well as take note of the data which has already been collected.

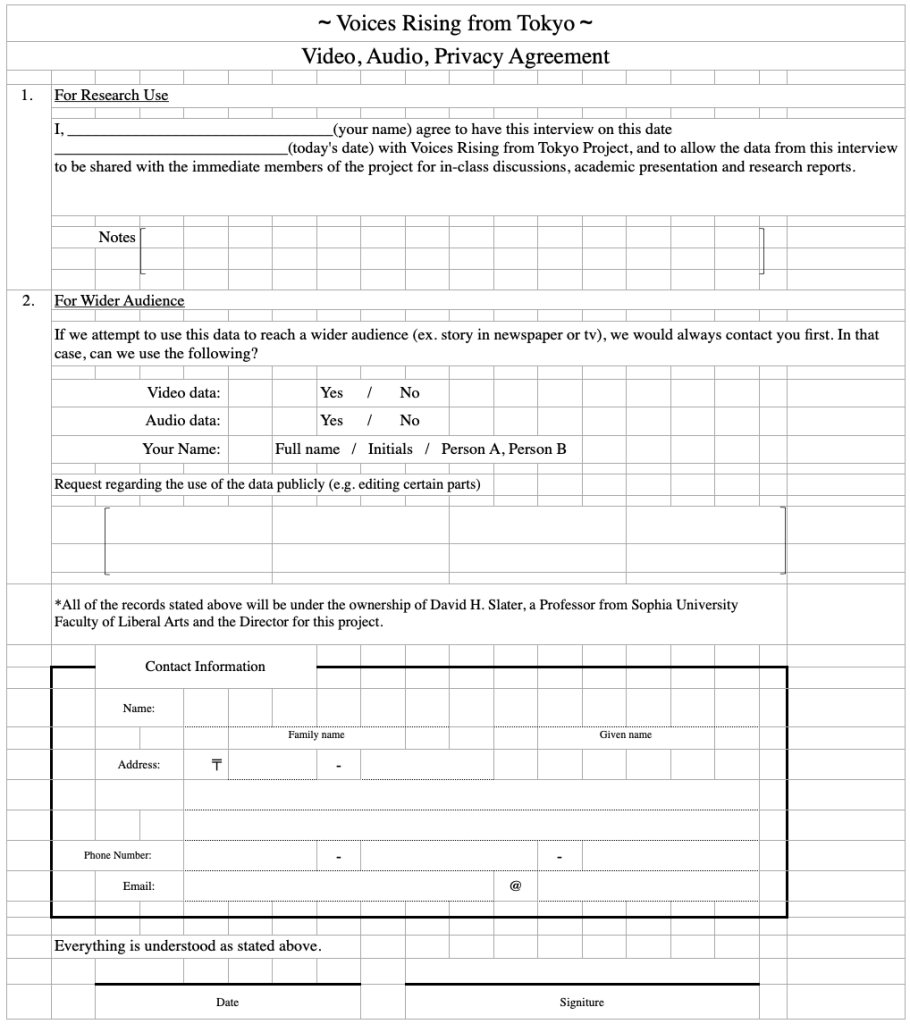

Before students are actually given any archived materials, they must read through and sign an agreement that stipulates the importance of the protection of all narrators’ privacy and rights. This includes that materials used in the class cannot be used outside of the course for other types of personal profit like selling it to the media or using it for other research projects.

The form is shown below:

After signing this document, materials can then be given to the students. An initial analysis of these transcripts allows students to grasp a few key aspects. First, they can get a feel for the narrator, the way they communicate, and the types of questions they respond enthusiastically to. They can also begin to get a feel for the topics which seem to interest or motivate the narrator, the social issues and political events that they deem important enough to highlight in their interviews. From this information, students begin to determine the main themes which could represent their narrators and begin to identify the areas which need further exploration and attention in future interviews. With this knowledge, students will begin their background research, especially on the country of origin, to better understand the complexity of the situation from which they fled, and thus to be prepared to ask informed and sensitive questions in their own interviews that follow.

After this introduction through archived footage, students are given a choice of which narrator to work with. If there is only one narrator during a semester then students are given the choice of which aspects to focus on. These groups usually consist of around 3-4 students who will then continue to work together on their narrator’s story for the remainder of the semester. With this decision in place, the class is ready to move forward with the main project.

Ethical Training

Arguably, the most important part of the process is the privacy and confidentiality forms which are handed to narrators when they agree to participate in this project. This informs narrators that their interview and transcripts will be used for the Refugee Voices Japan project which entails that it will be passed down as class material. However, the data will not leave the Digital Oral Narratives class. Any material that we want to show on the public website must be reviewed and approved by the refugee narrator. They are entitled to redact information or delete entire interviews from the archives at any time. The data is always under the control of the refugee narrator. This system ensures that narrators can feel safe in the knowledge they are in complete control over the data that they provide and hopefully this will act as a way to initially establish rapport.

“For our project, specifically, we are asking them to fill out a consent form. A lot of refugees have experienced negative incidents related to paperwork or legal procedures. We have to be very careful explaining what this paper means, explain that they can withdraw and what it all means”

Naho, 2020

These forms are signed at the start of the first interview, but all subsequent interviews begin with a similar re-statement of the confidentiality policy this project holds. A verbal ‘yes, I understand’ is received by the narrator each time, which though perhaps repetitive, is extremely important for us to ensure that they are fully aware of their rights. At the end of the interview, refugee narrators once again review and sign the form if they feel comfortable with the results of the interview.

The form used is shown below:

You will see that there is a place for the refugee narrator to give instructions. These include particular individual permission for our use of their voice, image and name. There is also a space for notes, which is usually used to give particular instructions to the interviewers in their subsequent use of the data. For example, “Do not put anything about my family in the public website,” or “Cut all mention of my work at XYZ from the master archive” so not even students in the project will see this information.

Methodological Training & Interview Technique

After understanding this key part of the beginning of every interview, students then move on to how to structure their interviews. Though question formulation comes later, elements of the interview technique are discussed at this stage. The importance of introducing main topic content is stressed to students as they create the outlines of the interviews. At the beginning of the interviews as well as at the start of each section of questions interviewees should allocate a sentence or two to explain the main topic they intend to address. This gives narrators a chance to get a feel for what the next hour or two will focus on as well as punctuate the interview to ground both narrators and interviewees in case the interview was beginning to stray off-topic.

In addition to this structure, students also begin to study the ways in which successful interviews are conducted. This means asking questions that address the gaps found previously when they went over past transcripts. They also must ensure that their questions, while academic in nature, are phrased in respectful ways which allow for narrators to express their ideas in an attentive and safe environment. Attentiveness must be expressed through active listening which remains mostly silent but always visible to the narrators through nodding and occasional verbal responses from the interviewers. This is in order to ensure uninterrupted audio when the narrator is speaking.

Another important interview technique is developing the ability to ask relevant and useful follow-up questions on the spot. Inevitably when a narrator is speaking, many intriguing, confusing, or unclear thoughts are expressed. It is the interviewers’ job to be paying attention to these details and asking follow-up questions to those points which should be clarified or further explored. This is a skill that is best developed through practice but it is at this stage that the concept is first talked about with the students of the class.

Coding & Question Formulation

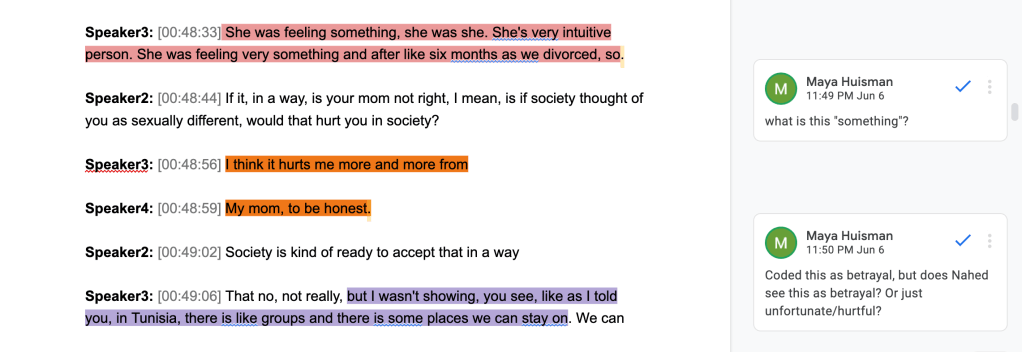

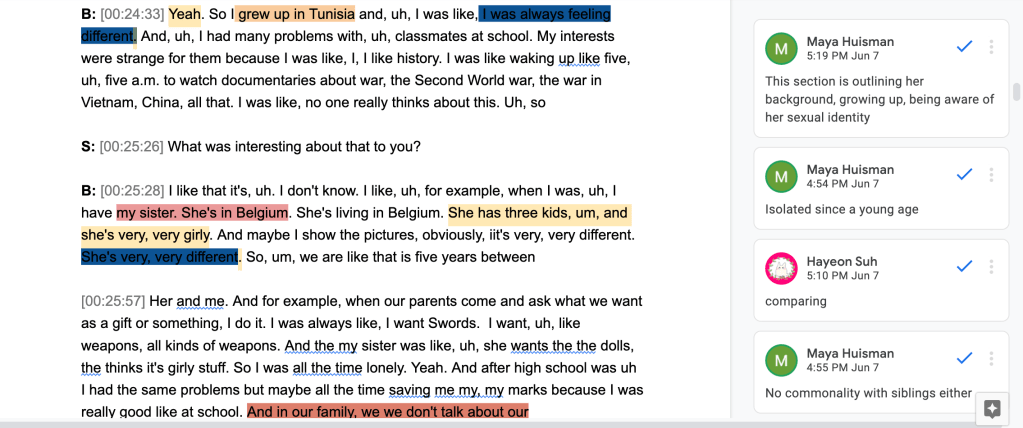

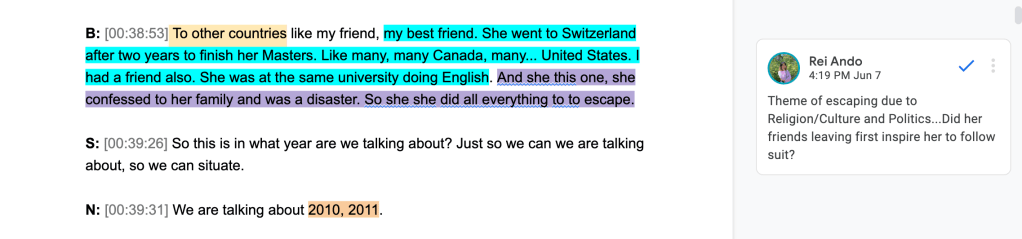

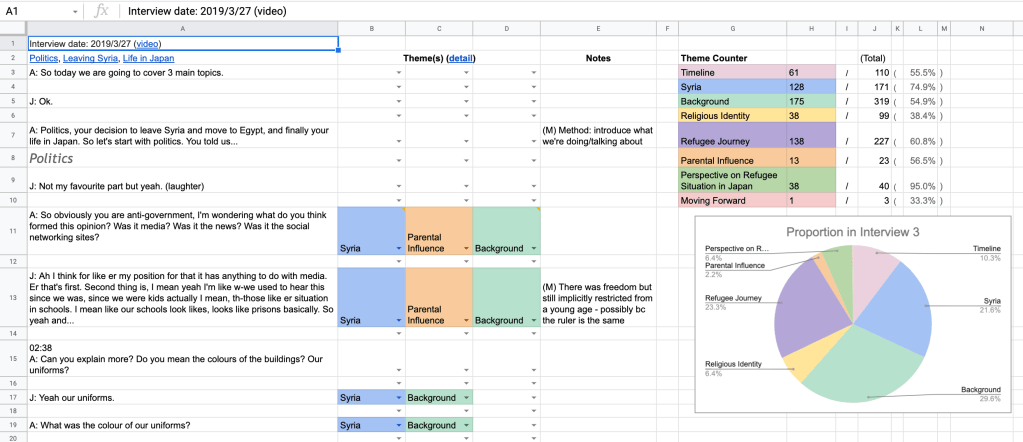

Once preliminary interview techniques are learned, the transcripts of the narrator’s past interviews are revisited. In a more in-depth approach, students begin a process called coding. First, the student groups are asked to consider the interviews and create several themes and sub-themes that encompass the major parts of their narrator’s story. Once these themes (about one to two per person) are decided on, they are allocated a specific highlight color and the team highlights all transcripts according to the theme. Students are also required to take side comments on the document with specific points about interesting statements as well as questions or clarifications they have. This document coding can also be formatted in excel, showing the exact percentage breakdown of the types of data recorded. This process allows students to have a clear vision regarding how much content is already available for each theme, as well as show which themes may need to be addressed more heavily in upcoming interviews. Coding is a collaborative process among all of the interviewers on the team, where communication, adjustment and flexible rethinking are the keys to having good codes. Below are some examples of what this coding looks like:

This Excel document is an in-depth approach to the coding process. The sub-themes and their corresponding colors are inputted into the spreadsheet. The spreadsheet can then be programmed to quantify the number of times a certain sub-theme has been highlighted, the specific quotes that have been highlighted, and the number of times a specific theme has been highlighted in proportion to the other themes. This gives a comprehensive idea of the content of an entire interview in one, neat document.

From this data, students are able to extract which themes they would like to address in the interview. From this point onwards, students begin formulating their questions. In 2021, we used Spradley’s Ethnographic Interview, and the class began formulating explanatory, ethnographic, descriptive, structural, and contrast questions pertaining to their main themes. This variety is important as it helps students to address key events and thoughts of a narrator from different angles, as well as making the interview itself more engaging for all participants. Questions are arranged into groups called ‘buckets’ which as the name entails are grouped according to theme and progress from general to deeper, more nuanced questions. Some of these questions may require some explanation from the interviewer’s side, as they can tap into different memories. Though they may cover interesting topics, it is important for students to understand why they are asking certain things, and be able to explain how it will contribute to the narrator’s page.

“My narrator James talked about things beyond my experience. I want to ask further because I’m curious but I really need to be careful how I phrase it and explain why I’m asking certain things. I want to make sure I’m narrating his story the way he wants it to be narrated and not just to fulfill my own curiosity.”

Naho, 2020

As students get a better sense of a narrator’s communication style, these interview question types may be more tailored to the specific narrator. Up until the interview date, these questions are continuously edited and refined with the help of the TAs and professor.

Background Research

At this stage, the students in the class are beginning to have a grasp on the narrator and the basic facts about their lives. However, what the Digital Oral Narratives class always wants to connect with is the macro-political and cultural context to which these narrators are describing their lives. This broader context provides essential grounding of the personal stories which are highlighted by the project, and therefore a basic understanding of the country and the social mechanisms happening within it must be researched.

“They are trapped in this complicated, multi-layered kind of persecution which can not be explained without understanding all the different factors involved”

Naho, 2020

Students begin by compiling research in order to create a sort of country profile based on the themes they identified during coding. By drawing from sources such as news articles, political party websites, academic journals, and YouTube news clips students begin compiling the external research material necessary to create an accurate picture of the macro sphere of socio-political context. Oftentimes narrators mention political events or cities casually throughout their interviews so this background research is crucial for interviewers to be able to better understand what their narrators are referencing. These sources not only provide important background helping the interviewer with mental notes during the interview but eventually, they will also be used as hyperlinks on the final website pages.

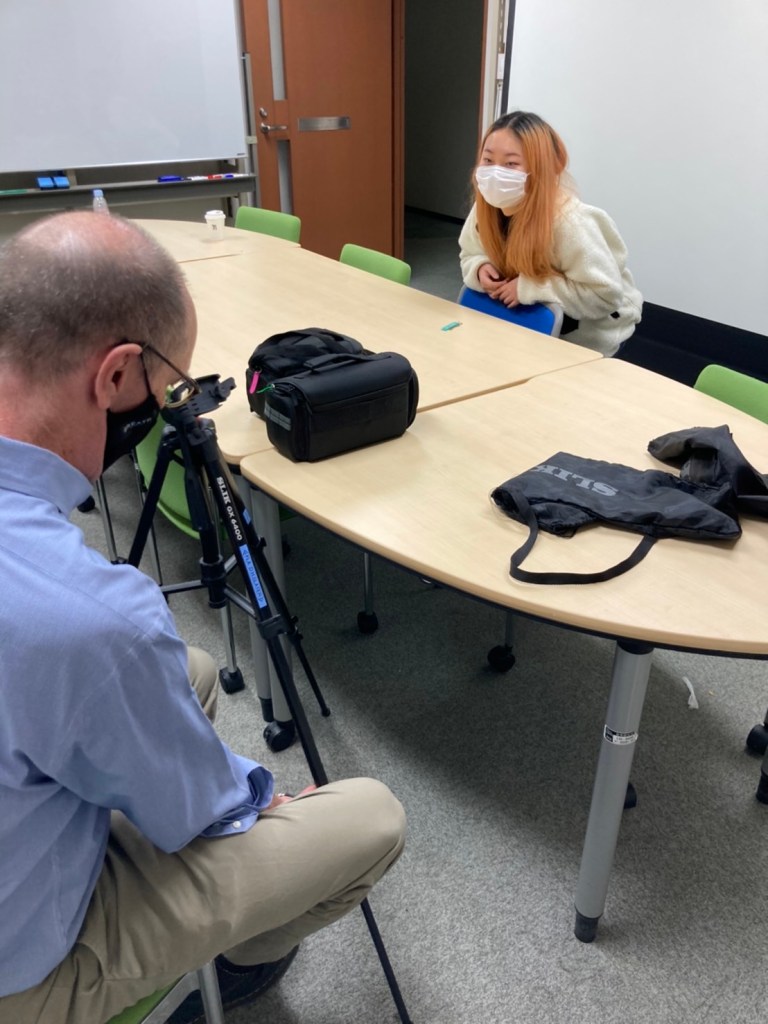

Interviews

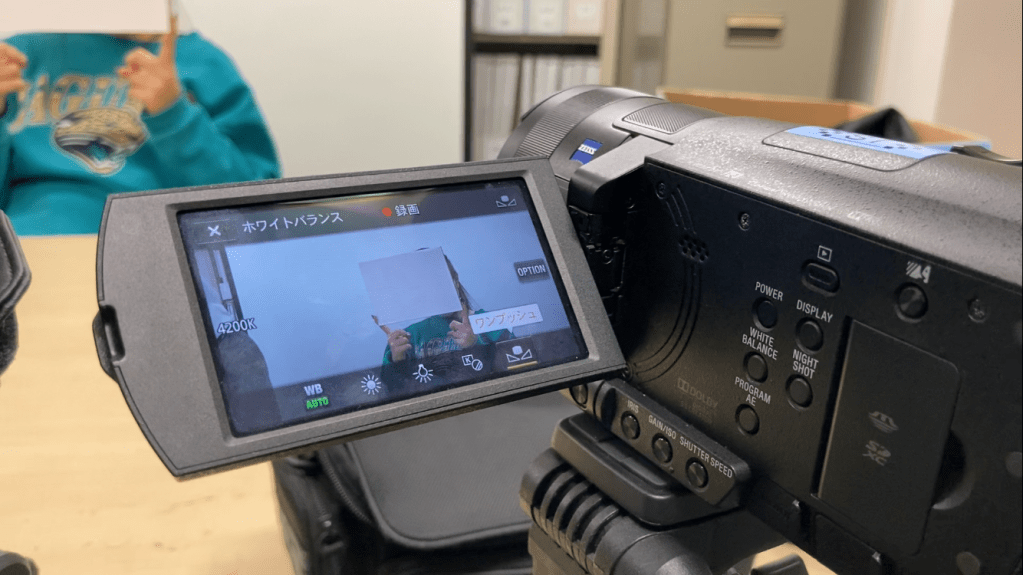

Narrators are invited to Sophia University campus for all of their interviews. Students spend time before the interviews setting up the interview room, camera equipment, and voice recorders. A camera as well as a backup are positioned directly on the narrator’s chair and are calibrated before and as the interview begins. This ensures that there are contingencies in place should something happen to one of the cameras or SD cards. Here is what a typical camera setup looks like:

When narrators are welcomed, there is typically a period of conversation and introduction that happens off-camera. This is in order to allow everyone to get acquainted and more comfortable with each other. Though this is an academic research project, the class values a welcoming atmosphere. Interviews typically last 1.5-2 hours and cover a few different themes. Each narrator comes in for multiple interviews.

As previously stated, all interviews begin with a restatement of the narrator’s rights and a brief introduction to the material being covered. Here is an example of what the start of an interview may look like:

Scripted Introduction

Okay, let’s get started! Hello. I’m Hayeon. And I am Maya. Nice to meet you. I am very happy to interview you today. Thank you for your time. I am going to be the lead for today’s interview and Maya will be the support. This interview will be about one and a half hours long, but if you like, we can talk longer since I and Maya have until 4:30. If at any point you need a little break, or some water please let us know that is totally fine. Today we are mostly talking about your life in Japan for the past 3 years such as your life in Tokyo, your recent move to Kyushu, the communities you interact with, Covid-19, and so on.

Before we start our interview, I know you have had interviews before and we already have some discussions through messages, but I will briefly go over some important points of the interview to remind you. This interview is part of our Digital Oral Narratives class taught by Professor Slater and his Refugee Voices Japan Project. Both audio and visuals for this interview will be video recorded and used for some academic purposes, for example in Slater’s class as well as the Refugee Voices Japan website. If at any point you would like us to pause/stop the recording, that is possible. If you would simply like to skip a question that can be done as well. Remember, you have the final say to anything that we publish, so you can tell us to remove anything that you don’t want after the interview. Professor Slater will be sending out another consent form at a later date, we will keep you updated on that as well.

Just to make sure everything is in working order can we just have you say something (test1,2) to make sure your audio is fine. (Your face has some shade on it, do you have a lamp in the room which we can move next to your computer?*backlighting*) (check video and mic)

Feel free to ask us questions at any point in the interview, but as of right now do you have any questions or concerns?

Maya, do you have anything?

Since there are multiple students present at each interview, this introduction also points out which student will take the lead for the interview. This person is called the ‘main’ and is responsible for going through the question buckets accordingly as written down beforehand. Their supporting students are called ‘subs’ and they are responsible for catching unclear terms that need clarification, digging deeper when interesting points come up, and asking follow-up questions whenever necessary. This style of interviewing was developed by David Slater during the research up in Tohoku. He explains,

“To keep track of where the interview is going and to be fully listening to what the narrator is saying - this is very difficult. So, we began to split these two functions, and have different people do each.”

David Slater, 2022

Throughout the interview, all interviewers are taking handwritten notes for their own personal use on the table in front of the narrators. Active but silent listening is encouraged in order to show engagement but otherwise, students are reminded to allow the audio of the narrator speaking to remain uninterrupted (this is for cutting video clips later). The main and subs also communicate throughout the interview by tapping each other when someone would like to ask a follow-up.

When the interview is complete, students ask the narrators to make some concluding remarks if they would like and then wrap up by thanking them for their time. The narrator is walked out of campus while others pack up the cameras and pass off the SD cards to the TAs for uploading online.

It is important to note that certain interview topics may be difficult for narrators to address. Violence, loss of life, and separation are very relevant to the lives of refugees, and talking about these events in depth can be emotional and draining. It is important that the interviewers take the necessary precautions and time to navigate these areas. Though we do not want to avoid these topics if the narrators want to talk about them, we always want to be considerate. The ideal outcome is for narrators to feel heard and respected.

“It was a pleasure for me too to work with you guys on this project… Thank you and thank the others on my behalf for all your effort on this project.”

Narrator, 2021

The data for the interview is then reviewed and analyzed in-depth right after the interview in a meeting with students, TAs, and the professor, in a “hanseikai”. This analysis is important not only to identify any remaining gaps of knowledge in a narrator’s story but to also address any areas for improvement on behalf of the students. Some examples of improvement would be better timing when interjecting follow-up questions, clearer phrasing for interview questions, better visible engagement from interviewers, or less audible sounds made by interviewers when the narrator is speaking. This step is crucial for improving future interviews and showing professionalism as a class.

Interviewing Under COVID-19

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the interview structure had to be changed in order to facilitate the necessary safety precautions. The overall content and interviewee positions remained the same but the interviews themselves were held entirely on Zoom using the recording function. This presented both assets and challenges to the interviewing experience. One of our students recount:

“By using the online method, we can include more refugees from various places, other than Tokyo or near Tokyo. In our case, we in Tokyo were able to communicate with Nahed in Fukuoka… [But] sometimes online makes us feel apart and less connected. When Nahed talked about her sensitive issues, it was difficult to express and deliver our feelings and attitudes online.”

Hayeon, 2021

Other concerns with online interviews were technical difficulties and bad audio or image quality. Some other benefits to online interviewing were the ability for more flexible scheduling as well as easier communication between the main and subs who could message one another throughout the interview with minimal visible disturbance. An example of what the online interviews looked like is shown below:

Cutting Clips

After the interviews, students revise all the content from past and present to start locating usable clips and quotes. “Clips” refer to the short, edited videos which are used periodically through a narrator’s website page. They are made for the purpose of having the narrator’s own words present in their story, for ideas that are best directly conveyed by them. This is often for topics that are emotional or deeply personal memories and therefore carry the most impact if presented by the narrator themselves. Similarly, written quotes are used for short sections of speech that are particularly poignant. These clips and quotes also serve to break up sections of writing and allow the narrator’s personality and face to take more focus.

The process of deciding what part of the interview will become clips and quotes begins with students highlighting sections of the transcript that they believe could be used for their particular sections. These possible clips and quotes are recorded with time stamps and organized within the initial outline of what they plan to write. These possible clips are discussed within the teams and confirmed if they are relevant to the section and impactful.

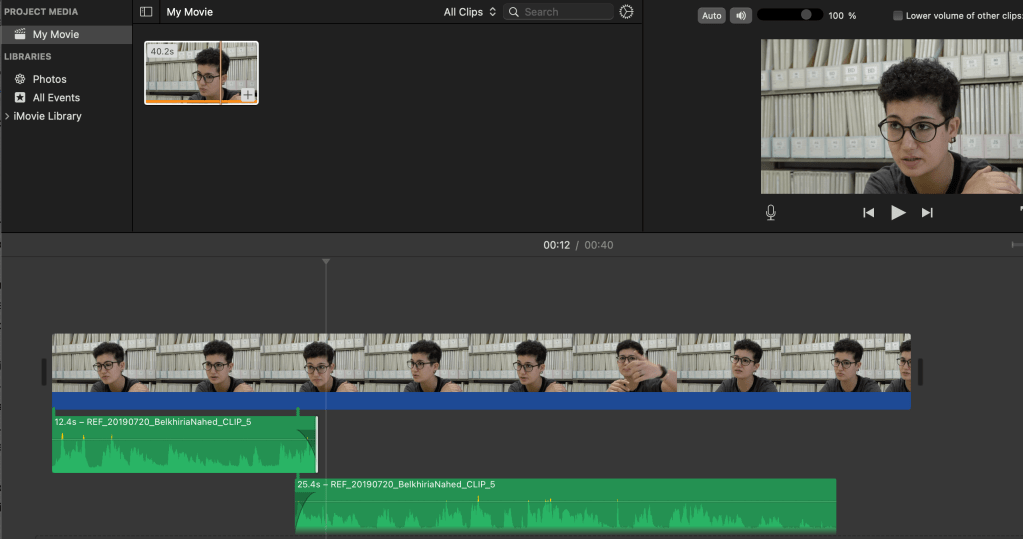

Students will then import the interview video into iMovie and shorten the clip to include the wanted dialog according to the timestamp on the interview. This is what a cut and overlapped piece of audio looks like:

These cut sequences can be dragged backwards and forwards in the timeline according to how you want to structure the video and the audio. When cutting there are a few aspects to keep in mind: Timing, picture, and fluidity of speech. Timing is important because cutting during a section where someone is speaking or about to do something makes the visuals seem abrupt and unnatural. Seeing the face of the narrator is crucial, so when the narrator turns their head away from the camera it may be pertinent to use a visual from B-roll. The fluidity of speech is important to ensure the clarity of the point the narrator is trying to make. If the audio sounds like it was cut abruptly, it may disturb the listeners.

There are a few ways students can edit these clips in order to ensure the three key points above. Jump cuts are abrupt and should be avoided usually but can be reminded with B-roll footage if the content of what the narrator is saying is important. J-cuts are used when splitting video clips by bringing the audio from the following scene to start in the clip of the previous one. L-cuts are simply the reverse of J-cuts. Both of these techniques allow for a more seamless and fluid visual and auditory experience for website viewers. Students take a lot of time to edit and re-work about 20-30 clips which average around a minute each. When finished the clips are saved on iMovie and exported to a private YouTube account used by those compiling the website.

What is key to making a ‘good’ clip is to ensure that the content conveys important, personal information.

“It is important to make sure the clips are used wisely. They can be powerful or useless…Always if you are choosing to show their face, make sure it is improving the quality of their story”

-Rosa, 2019

Clips that only convey information that can be easily written as expositional information are not as impactful as those which convey feelings or personal experiences. This does not necessarily mean that all clips have to be very emotional, rather they should be thought-provoking and interesting. Moments that are awkward or not relevant to the page’s contents should also be avoided, as well as those with bad audio quality. If done correctly, the students will have a series of short, impactful clips added periodically throughout the webpage which adds immeasurably to their narrator’s story.

Here is an example of what the original clip looks like and what the edited clip looks like in comparison, in the case of the clip used in the introduction of our narrator Yasser’s page Growing up Under Assad’s Regime. The original 105-second video was cut into a 34-second trailer-like clip that effectively catches the readers’ attention and illustrates the key themes in his story through the following steps. For a more detailed breakdown of the editing process, read the transcript here.

- Cut the interviewers’ voices, content that needs further explanation, and irrelevant information

- Color code by themes (emotions in this case) and identifying the important quotes

- Decide on focusing on the key emotion “fear”

- Cut some awkward parts within and between sentences so it flows better

Writing & Publishing

The writing process truly begins after usable clips are located and created. The outlines that have been made at earlier stages and revised, rewritten, and expanded to be more comprehensive to include clip and quote support. From this detailed outline, students begin drafting their website pages. Though student groups work together to compile one narrator, each student usually creates their own sub-page, based on a particular theme or chronological arc of their narrative. While they will get feedback from other students as they write, a single student will be responsible for each section.

An important note to make about the tone of the writing used for this project is the unusual break from the academic vocabulary. Due to the nature of this project being a website constructed for an audience of the Japanese and English speaking general public, the tone is more journalistic in nature. This means minimal academic terminology and less analytical language. Instead, students are taught to weave in macro socio-political contexts with individuals’ voices and life experiences resulting in a complete analysis. By writing in this way, students convey a narrator’s story in a comprehensive, yet still personal way for an audience who may not be familiar with the countries or political events that are being referenced.

“You want to deliver the narrator’s voice, not yours. I knew about refugees but not about this style of writing… I think a lot of students struggle with it.”

-Naho, 2020

As the sections are being drafted and edited, TAs and Professor Slater continuously revise and give comments. Team members also come together to discuss and edit each other’s content, advising against possible overlaps between their individual subpages, more in-depth analysis, and constructing specific links to subsequent pages. This process of writing and editing repeats itself multiple times as students strive to refine the content in order to create a comprehensive, well-worded account of their narrator’s experiences. This pressure in producing a final webpage that both the narrators and students are proud of is what drives the class to create rigorously edited and polished work.

“It helped me become more thoughtful about what I do and how I treat people. It also sparked my interest in refugee work… I found what I want to do.”

-Rosa, 2019

One of the final steps of the process is taking the final drafts of the website page and forwarding it to the narrator. We do this in order to receive their approval for their own story which is important to reinforce that all narrators have complete agency over their data. It also gives them a chance to make minor changes, or correct us if we have made any mistakes. Nothing is published on our site until it has been approved of by the narrator themselves.

Once we have received the final go-ahead for the narrators, the website pages can be published on this website for the general public to read. All of these pages are the culmination of students’ effort and energy for an entire 5 month semester. This class, while demanding, has been the highlight of many of its contributors’ university journeys.

“My biggest takeaway is how significant it is to work with individuals. Everything that you see on the news may feel far away, but behind it, there are always people who are experiencing it.”

-Ayano, 2021

Written by Maya Suzuki Huisman, student and TA of David Slater’s Digital Oral Narratives class of 2021

Find out what the published material looks like and the story of our narrators below.

Ariana

Fleeing Iran due to discrimination and violence experienced as a woman, Ariana has advocated for Iran’s future free from oppression and the return to the Pahlavi dynasty. Despite facing more challenges as a refugee in Japan, her activism for human rights continues through social media.

Guillain

As a gynecologist and activist, Guillain escaped political persecution in Congo and sought refuge in Japan. Despite facing challenges with refugee recognition, he resiliently forges his way through and continues to work towards a world of equality, upholding his lifelong commitment to helping others in need.

Nyo

Nyo grew up under the dictatorial military regime in Myanmar and came to Japan seeking safety after the violent suppression of the democratic uprising in 1988. Although his life in Japan was difficult for a long time with severe restrictions on his everyday life, Nyo is happy with the freedom he found here.

Sana

Growing up in Ghana and Burkina Faso, Sana suffered persecution by an Islamic militant group due to his engagement in social activism. Although he fled to Japan for safety with his parents’ support, he then had to choose detention over deportation, where he met with physical and psychological torture.

Patrick

Patrick was born in the English-speaking region of Cameroon and was forced to flee when his life was threatened amid the ongoing civil war known as the Anglophone Crisis. While he may have found immediate safety in Japan, he has also faced arrest, detainment, and restrictions under provisional release.

Christopher

Christopher was an activist in Cameroon who fought for workers’ rights, which eventually led to his persecution by the government and forced him to flee. Despite his hopes for a better life in Japan, he has faced various difficulties through years of seeking asylum and the eight months of detention.

Nahed

Nahed was born in Tunisia, North Africa, where she experienced isolation, harassment, and abuse from a young age due to her identity as an LGBTQ person. The influences of the Tunisian Revolution, Islam, and rigid social expectations of men and women in Tunisia have contributed to shaping Nahed’s journey.

Yasser

Fleeing the Syrian conflict, Yasser came to Japan with his mother and his younger sister. Since then, he has taken care of them, balancing challenging work and student life at Meiji University. Now, he is one of the few recognized Syrian refugees, a successful actor, and a social media personality in Japan.

Ozzy

Ozzy was just 13 when she and her family were detained in Japan on their way to flee to Canada from civil war and persecution in Liberia. Although they sought asylum in Japan instead, the pending decision has constrained her to a new restricted life here on provisional release and an uncertain future.

James

As a young male in the minority English-speaking part of Cameroon, James experienced a great deal of discrimination and violence by the government and military before leaving his family to flee to Japan. Through all the difficulties he has faced, his faith in Christianity has been integral to his endurance.

Sunday

Sunday was born in 1970 in Uganda. He was passionate about political activism for democracy from a young age, for which he ultimately suffered persecution. Forced to leave behind everything to survive, he made his way to Japan in 2007 and has fought for refugee recognition in court and detention since.

Gabriel

Gabriel began to receive death threats from the extreme Islamist group Boko Haram for his published book that taught Christian beliefs. Not being able to return to Nigeria, he sought asylum in Japan. His 30-year journey to refugee status was not easy, with heavy restrictions inside and outside detention.