Upon leaving the prolonged violence and fearing the possible repercussions of renouncing her Islamic belief, Ariana initially was hopeful to stay and live in Japan; she thought the government would give her refugee recognition and the support she needed for taking care of her family and being an activist. However, going through the long, unwelcoming refugee recognition process, she noticed the reality that the Japanese government was not willing to help her. Ariana’s experiences and her reactions toward them exemplify an unrecognized refugee’s hardships, but also her resilience and positivity. Despite being in a difficult situation, particularly in the dehumanizing bureaucracy where she feels her identity as a human being is undermined, she tries hard to maintain her own identity and to be herself, seeking what she can be grateful for.

1. Application for Refugee Recognition

1.1. Introduction

Ariana came to Japan with a two-week tourist visa, hoping to get a job and refugee recognition, which she deserved as a political refugee with children to protect. It was crucial for her to be legally recognized as a refugee to acquire a stable job and have a safe place to be an activist.

In the 1951 Refugee Convention by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), a refugee is defined as someone who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail [themself] of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of [their] former habitual residence, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

Since Ariana is facing the danger of being persecuted due to her abandonment of Islam and her political opinion, she has a legitimate reason to be unwilling to return to Iran. Therefore, Japan, being a country that signed the convention, should legally recognize her as a refugee. However, this does not mean that Japan is legally bound to do so, as the convention does not have such power. Thus, Japan’s commitment to the convention is low, having strict refugee recognition standards and rejecting applicants who show even slight inconsistency in their words or lack of objective proof of their persecution. As a result, Japan’s refugee acceptance rate is around 2 percent, significantly lower than other countries.

Ariana soon learned about this notoriously low refugee acceptance rate and realized the very low possibility of her being a legally recognized refugee in Japan. She attempted to look for a visa at the Canadian and German Embassies in Japan, soon to find that it was unavailable for her as she did not have a zairyu (residence) card. Combined with the disappointment of not being able to get a job, with all her confusion with the difficulties in gathering information, Ariana says she felt like an insect traveling in a spider web. In the spider web, the best she could do was to apply for refugee status with very little hope; she went to the immigration bureau shortly before her tourist visa expired. What awaited Ariana there was a long, thorny path of the refugee recognition process.

1.2. Diving into the Refugee Recognition Process

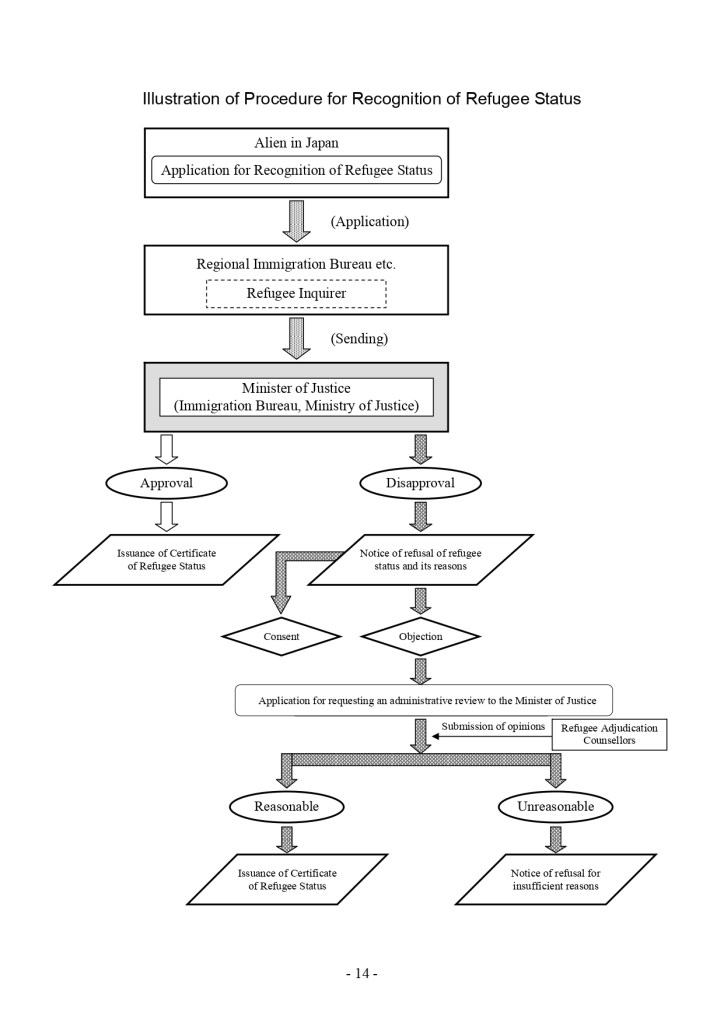

The refugee applicants first have to submit the necessary documents: the application form, two photos of the applicants, and a document proving or a statement claiming that the applicant is a refugee or a person subject to supplementary protection. The last one should only be submitted in Japanese, making the application very difficult as most refugees cannot find or afford a translator to complete the document. Luckily, Ariana was able to find a Persian interpreter with the help of the Japan Association for Refugees (JAR).

After finally submitting the documents, the applicants go through interviews with immigration officers. This process is notoriously long, inefficient, and emotionally draining. The officers are not necessarily specialized in immigration laws, and their ways of deciding the legitimacy of the application heavily rely on making sure the provided documents and proofs are not fake. To do so, the applicants are put under heavy scrutiny and often have to repeatedly talk about their experiences again and again. A small inconsistency in the details of dates and names in their words – which are normal things that humans forget by nature – can lead to the judgment that they are “lying” and making a false claim. This process was particularly difficult for Ariana as she, unfortunately, has developed short-term memory due to her experiences in Iran. This made it difficult for her to accurately recollect and repeat her story, bringing her a huge disadvantage in her application. Not being able to fully recall the story or recite the words, she would worry that she was considered “lying” and that it would lead to the rejection of her claim.

1.3. Cruel Interviewing

Ariana had to undergo five long interviews. Although she was luckily able to have language support, she did not receive any legal support, such as a lawyer. Ariana initially had a high expectancy of Japan’s human rights standards; she believed that Japan, as one of the most developed countries, would give her refugee recognition to protect her rights to a safe life with enough money to sustain basic living conditions. However, Ariana says the officers’ words were shockingly contrasting to such an expectation. When she brought this topic up and mentioned human rights in the interview, she said the officers laughed saying “What is human rights? What is freedom?” and told her to go back to her country. Although conflicted by the cold words of the immigration officers who she thought were there to help her retain safety and dignity, Ariana uttered “I’m not an enemy, I’m a friend,” indicating her harmlessness to the Japanese nation and her dire reality that she was unable to return to her home country. The officers’ unwelcoming attitude against her initial expectations towards Japan saddened her and caused her to lose hope.

Note: This narrator’s face is blurred at their request for privacy.

This was not only the case for Ariana. The series of interviews is one of the most challenging processes in refugee recognition in Japan, not only is it long and ends in vain for a lot of asylum seekers, but it also imposes emotional demands on them through heavy scrutiny and questioning of their trauma, which is already extremely difficult to talk about. Moreover, refugees often share that the interviewers’ attitudes can be harsh or even hostile, as seen in her case. Unlike the practices in other countries, lawyers and recordings are not allowed during refugee application interviews in Japan. Therefore, the applicants – except for the lucky ones who got a translator – go through it all alone, with no one to assist with legal knowledge and effectively claim their rights to be protected as refugees.

Ariana describes that the interviews were more like interrogations. She felt that they were done in a way to paint her as a liar and question her past decisions. Such scrutiny made her feel like she was treated as a mere “case,” rather than a human being. This feeling of not being heard is not a singular experience of Ariana’s, experienced by those who endure the circuitous process of applying for refugee status.

For instance, the officers repeatedly questioned her decision to leave her family in Iran. These questions were not ones that could gather necessary information for her refugee recognition, but rather just criticize her and hurt her feelings. Japan’s refugee recognition, according to the government, is made strict so that the so-called “fake refugees” who come to Japan and seek refugee status to get a job will not be accepted as refugees. However, as illustrated by Ariana’s story, the strict system is not helping, but rather damaging “genuine” refugees like her. In fact, many people who have valid reasons to seek refugee status are instead faced with rejection, usually with no or unsound reason.

1.4. Waiting…and Rejection

Upon being emotionally and mentally tolled during the interviews for refugee status, Ariana waited in a limbo state for the result of her efforts for nine months. While waiting for the result of the application, she soon learned that there were not many possibilities that she could stay and live in Japan with a stable status. Still, she did not have any other choice than to stay in Japan and wait for the refugee recognition with little hope. Because she needed a work permit as soon as possible to be able to support her family, the nine months for her was very long. However, in comparison to the other refugee applicants, perhaps Ariana can be considered as lucky; in 2022, the average waiting period for the first application was two years and nine months. While Ariana’s refugee application took a relatively shorter period to reach a verdict, she nevertheless feels like her time is disregarded in Japan.

Japan is well known for its systematic and punctual ways of living, where train conductors apologize for leaving 20 seconds early. Residing in Japan for almost seven years, Ariana sees that Japanese people are hard-working and the system is very sufficient. For instance, the juminhyo (residence certificate) issuance in Japan is typically a same-day process, while in other countries, it could take several days or weeks. While the efficiency applies more for Japanese citizens, she genuinely admires it as she strongly believes in the importance of working to make one’s own country a better place.

“ I was very sad, but I could understand the Japanese government. I was not angry with them, never. I thought this country is very beautiful… Japan is very successful. And the Japanese people and government worked hard to make this country great. If we want to make a beautiful world, we need to make a beautiful country before that.”

She also appreciates the fact that the government here protects Japanese people and non-refugee foreigners’ human rights and women’s rights, contrary to the current government in Iran. Nonetheless, being a foreigner with insufficient Japanese language ability, which, combined with her status as an unrecognized refugee, only provides her with the opportunities to do manual labor. She feels she is not considered necessary in this country and thus excluded from Japan’s protection.

After waiting for nine months, her claim of being a refugee was denied and deemed illegitimate. Because Ariana initially expected much higher human rights standards in Japan and thought the country would help her, especially concerning the situation with her family, she became very disappointed after knowing that was not the case.

She thinks that the protection of human rights, which is often adopted as a slogan in many countries, is superficial and not cared about much even in developed countries. For example, Japan, while having signed the 1951 refugee convention and thus shown its attitude to protecting refugees’ human rights, have severely violated refugees’ human rights in the detention center. This is represented in the case of Wishma Sandamali, a Sri Lankan woman who died in detention without adequate medical treatment for her illness.

2. Financial Support: A Glimpse of Hope

2.1. The Bright Side of Japan

Living with no financial capabilities to support herself, Ariana sought to seek help from the government through other means. She learned about seikatsu hogo (生活保護) – translated to English as “livelihood protection”– from her City Hall. Seikatsu hogo is Japan’s measure to guarantee the minimum standards of healthy and cultural living stipulated by the Constitution to people who are in poverty, and it is a citizen’s right to apply for it. However, seikatsu hogo is, in practice, not only provided to Japanese citizens; while foreign people are not originally eligible as they are not “Japanese citizens,” they have been given the eligibility for benevolence.

While there is a limitation that foreigners cannot appeal in case they are rejected, Ariana successfully was seen as eligible and started receiving seikatsu hogo in 2023. Despite not having a clear vision of the application procedure due to the language barrier, Ariana says she did not experience difficulties and rather has had a good experience regarding the process thanks to her case worker who helped her through the process. She says that thanks to her, all she had to do was sign the papers as she trusted the city hall and the government for the Japanese people’s hard-working nature, which she has repeatedly expressed admiration for. She describes the caseworker as a serious and good woman who tries hard to do her job, always trying to be fair while staying neutral between kindness and strictness. She illustrates the caseworker in contrast to the immigration officer: On one side of the bureaucracy, the immigration officers act very strict and hostile – which she understands as their roles that they have to play, suppressing their compassion – and on the other side, the caseworker, who also tries to maintain her work within her role, can be fair and neutral.

She is very grateful for getting to receive seikatsu hogo from the government because it relieves her guilt of bothering others for her life. Feeling guilt and being ashamed for getting support is common among refugees, as they often feel like they are burdening others with their needs. For Ariana, it particularly feels guilty to ask for help from people around her, as she feels like she is bothering others for her life.

Of course, the primary significance of governmental support is not to relieve guilt, but to legally assure people to maintain the “minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living,” as written in the Constitution of Japan. However, although financial support alleviates some portion of a person’s life such as the necessities like rent and food expenses, it is still not enough to cover other aspects of life, such as nutritious food, hygiene, and transportation. Therefore, countless refugees still need to “beg” and require support to maintain their lives in the urban setting, leading to feelings of indignity and guilt.

2.2. Difficulty of Living with Seikatsu Hogo

Ariana feels she is very lucky to be able to receive such governmental support. Still, living with seikatsu hogo has made her experience difficulties. One difficulty Ariana has is the accessibility to medical care. Because she suffers from kidney problems and depression, she needs to see a doctor constantly, sometimes urgently. However, because the insurance from seikatsu hogo only covers the medical fee for a single designated medical institution, which means her financial status only allows her to visit one clinic among all others when she is sick. Even when the clinic does not provide specific treatments for her medical problems, or even when she is sick in a place far from the specific clinic, she practically has no choice but to go to the one clinic which seikatsu hogo covers the fee for. One day, her kidney started aching severely when she was far from home; it was too severe for her to ride a train and see the doctor at her designated medical institution. Fortunately, she was with a refugee support group at the time and was able to see a doctor and get medicine as the group covered the medical fee. However, she otherwise would not have been able to go to a clinic nearby, and this possibly could have resulted in a serious problem in her kidney. Because of this difficulty in seeing a doctor, combined with the language barrier of communicating with the doctors, Ariana often decides to stay at home rather than go see a doctor, which leads to increasing the risk of insufficient cure for her medical condition.

Moreover, from her personal experience, she has experienced cases in which institutions and workplaces expressed disappointment after she revealed her status as someone with seikatsu hogo, and even rejected her after she did so. She recognizes that this problem is not because she is a refugee or a foreigner; it is particular to seikatsu hogo, and the same thing can happen to a Japanese person with seikatsu hogo. While it provides a significant financial help, seikatsu hogo entails a stigma that is unique to this particular form of governmental support, adding additional mental and practical burden on Ariana to being a refugee.

3. Sense of Identity in Japan

3.1. Zairyu (Residence) Card

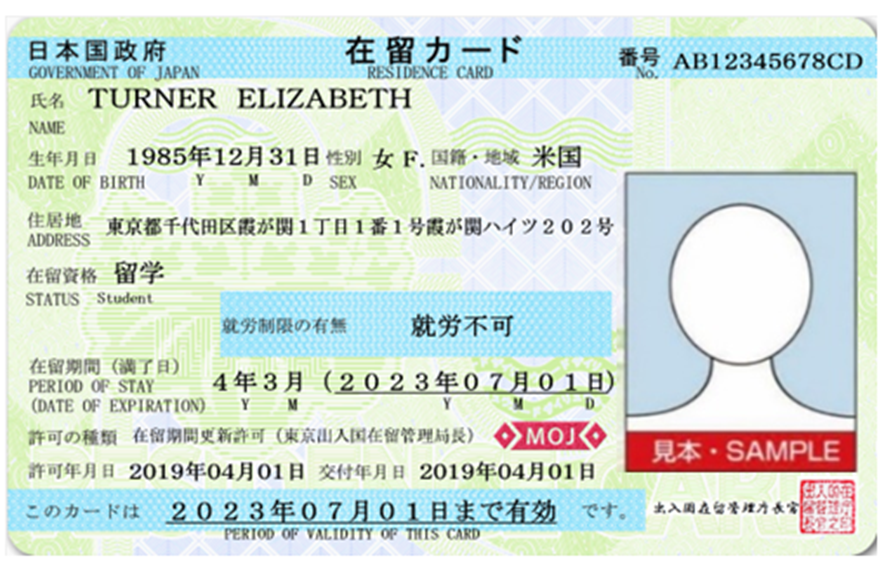

After the initial application for refugee status, Ariana waited for nine months to acquire the Tokutei Katsudo (Designated Activities) visa, which provided six months of residential status, the permit to work, and a zairyu (residence) card. This visa is typically given to refugee applicants who are waiting for the result of their application. Spending nine months without it was not easy for her, not only because she could not work during that period, but also because it shadowed her sense of identity in Japan. Ariana is a person with a strong sense of identity – as a woman, a mother, a political activist, and an Iranian. Yet, the lack of a legal identity in Japan struck her as a sense of living without an identity. Legal identity, apart from one’s personal identity, plays a significant role in the sense of belonging through acquiring a social status in the place where the person resides. This is why she was very happy when she acquired the zairyu card and finally gained her legal identity in Japan.

Not only the sense of identity with the zairyu card but also the permit to work has given her the sense of being “useful” in this country – this is very important as she believes that she has to be “useful” for Japan to stay here without “bothering the country.” Ariana is currently staying in Japan with the Tokutei Katsudo visa, which she has to renew every six months. This is not a stable “permanent residence,” and the failure in the renewal process can put her in the detention center. Nevertheless, the sense of identity and the permit to work gave her was crucial for her to be a “regular” person who resides in Japan.

3.2. Being an Unrecognized Refugee in Japan

Ariana is currently not legally recognized as a “refugee” in Japan, as she is waiting for the result of her second appeal and living with the Tokutei Katsudo visa. However, despite all the difficulties and disappointments, her attitude towards this difficult situation represents her positivity and gratefulness. She is thankful for all the help she has got and the situation that she is in, as she can now comprehend the hardships people face, enabling her to help others experiencing difficulties.

“I try to respect myself as a human.”

Similar to what she has mentioned about having seikatsu hogo, she says that her status as a refugee can change the situation that she is in; in her case, the kind of job that she can acquire is low-paying, temporary, manual labor due to her status. Moreover, she says that showing her ID to reveal her status as a refugee can bring a sense of shamefulness just by being a refugee. Although she had done nothing wrong, she feels like being a refugee is regarded as something she should be ashamed of as if she is a criminal. However, she says she tries not to feel a sense of shamefulness and tries to respect herself as a human, not a refugee. This reveals a significant truth that is obvious yet often forgotte; the “refugees” are individual human beings who happened to gain the temporary status of “refugee” in their lives, and it is not a fundamental nature of them or an innate identity that they bear. Ariana is a human being before a refugee, and deserves the treatment as an individual with her own identity – which is much more than just being a “refugee.” Because she knows this herself, she tries to maintain her dignity as an individual human being, rather than being ashamed of her status.