1. Mamfé, 1990

Southwestern Cameroon (Anglophone region)

“It’s hard to remember the timeline of my life in Cameroon, because something always took me from here to there. But I have changed much since my childhood. If you were in my place, you would have changed a lot too, after two years in the detention center. You can’t be the same person again.”

Patrick was born in Cameroon – a country where, now, the language you speak could cost you your life. Since late 2017 Cameroon has been engulfed in deadly conflict and civil unrest. Cameroon is ideologically and linguistically divided between the Southwestern (Anglophone) regions and the majority surrounding (Francophone) regions. Historical marginalization has spurned separatist protests in the Anglophone regions, while attacks in the Far North region by the Islamist armed group Boko Haram began in 2021. The government has responded with unlawful killings and arbitrary arrests, breaching international and humanitarian rights laws.

As of 2022, over 712,000 people were internally displaced in the Anglophone regions and at least 3.9 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. But before Patrick was forced to flee his home and country, one among at least 80,000 Cameroonians who fled, Patrick lived in the Anglophone region of Cameroon.

Patrick was born in Mamfé in 1990 – 30 years after Cameroonian independence was declared. At the head of the Cross River which stretches through western Africa, branching west into Nigeria and flowing upwards into the highlands of Cameroon, sits a town called Mamfé. Nestled near the center of Cameroon’s Western region, Mamfé is home to a population of around 32,000 belonging to 11 autonomous villages and a plethora of Cameroonian tribes, who were drawn to the promise of the land’s fertile soil. Palm oil and kernels, bananas, cocoa, coffee, and more abound in the markets of Mamfé.

“What can I say about Mamfé?” Patrick wonders fondly. “Apart from the fact that there, people are so good, so kind. In my village – in fact, in Africa generally – when you enter a little locality… the way people receive you, mostly when you’re a foreigner – I’m sure that you won’t even think about leaving anymore.”

1.1. Cameroon: Crevasses from a Colonial Past

Before Cameroon became divided into the Anglophone (English-speaking) and Francophone (French-speaking) regions for which war rages today, it was a country divided by colonial powers. At the onset of the European colonization of Africa, in 1884 Cameroon was first a German colony.

It is said that the Germans first arrived in Mamfé by way of the Cross River. The Germans, upon arriving in the new area, questioned a local who was working by the shore of the river. Not understanding their questioning, the local man asked in his Bayang dialect “Mamfie fah?” (“Where should I put it”?). Misunderstanding his reply as “Mamfé”, the newcomers thus named the area.

But following the German exile during World War I, the Cameroonian landmass as it is seen today was fragmented by British colonial rule over its southwestern region – labeled “British Cameroons” – and French colonial rule over the rest of the territory – labeled “French Cameroun” in 1916.

British rule over southwestern Cameroon was “a period of neglect” however marked by agricultural developments and the unification of plantations in the area into a single, government-owned Cameroon Development Corporation. However, these developments paled in comparison to French Cameroun’s agricultural, industrial, and infrastructural growth. By the 1960s – the period nearing Cameroonian independence – French Cameroun largely surpassed British Cameroons in GNP, higher education levels, health care systems, and infrastructure.

Right: Cameroon today, divided by language (Wikipedia)

Following a civil war between nationalists and French forces, independence was granted to French Cameroun on January 1, 1960. Ahmadou Ahidjo was elected president, and together with his party Union Camerounaise, led the promise of a capitalist economy and close relations with France to establish a united, independent Cameroon. In 1966 the party would later merge with the Kamerun National Democratic Party (KNDP) and rebrand itself. Today, it is known as the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (Rassemblement démocratique du Peuple Camerounais) or CPDM. Since the 1960 independence, CPDM has dominated Cameroonian politics.

Meanwhile, former British Cameroons were at a crossroads. On February 11, 1961, a United Nations-supervised referendum was held, with two options: to unite with the Federation of Nigeria or the Republic of Cameroon, with no option of separate independence. The Christian-majority south voted for unification with former French Cameroun.

Today, Mamfé, the entire Southwestern Cameroon, and neighboring Nigeria still share something beyond a similar colonial history: people from these regions speak English. It is a fact impossible to ignore; because Southwestern Cameroon is often called the Anglophone (English-speaking) region and the majority rest, the Francophone region (French-speaking) regions of Cameroon.

Many, then and today, call it a divide. The divide. But for Patrick, coming of age in the looming backdrop of these intangible yet increasingly demarcated differences – it all did seem nonsensical. After all, Patrick’s childhood is similar to many young people in Cameroon. In a place where, as Patrick recounts, the attitudes of respecting, honoring, and warmly receiving others no matter where they come from permeates, Patrick was always surrounded by friends and family growing up.

1.2. The Picture of His Father

The second eldest child of seven siblings, Patrick was born to a mother from the Anglophone region and a father from the Francophone region. Patrick’s mother is of the Bakweri tribe, and his father is Bamileke. This so-called Cameroonian ‘divide’ dissolves even within the realm of Patrick’s childhood home.

“In our house,” Patrick describes, “there are some who speak more English than French; others speak more French than English, like me. A very strange house!” He laughs.

Patrick thinks it’s strange that they speak English and French at home, but barely their mother’s or father’s languages. “Everyone in our area speaks Pidgin English,” he tells us, “and I really regretted not being able to speak my mother’s language. Once, I told her, it’s no good that we can’t speak Bakweri. We’re supposed to be raised with our maternal language.”

“One of the qualities that my parents appreciated me for is that I know how to gather people easily.” An approachable and grounded individual, Patrick would often play peacemaker between his friends and siblings. When a male friend has trouble with his girlfriend, for instance, Patrick is the one to ask for help.

“For me, speaking to people is very easy. My friends knew to come to me for help to make peace among them and their partners, and it’s always easy for me.”

Both his parents’ tribes practice patrilineal inheritance and succession, and there seems to be an emphasis on the role of the eldest male in the family. “But for my older brother, life is just to enjoy. My mom used to call me to look after my older brother.” Patrick seemed to be the child his parents would depend on to sort disputes, convince, or speak reason to his other siblings.

It seems that in many ways, Patrick grew up closest to his father. “When my father was still alive, whenever needed help – to gather students or workers… He would appoint me, Patrick, please help me with this. That’s why he chose me to be his supervisor later on.” Patrick describes him as kind, never aggressive, and his greatest source of inspiration. “He helped me discover who I truly am.”

Patrick’s father was also the perfect gentleman. Patrick loves to tell the story of how his parents met, despite coming from two different tribes in two different regions of Cameroon. “One day, there was a party near where my mother lived at the time. My mother was only at the party for a short time, but he saw her that day for the first time and immediately took a liking to her. He later asked a cousin, Who was that lady?” Patrick would tease his father about it – you came for the party and you were concentrating on a lady! After that, Patrick’s father started writing letter after letter for her. And one day, he traveled to Mamfé just to see her and asked her parents for her hand. Seeing how responsible a man Patrick’s father was, the answer was a clear yes.

“My dad was like a lamb, my mom was like a lion.”

A lamb, yet a shepherd. Patrick’s father was a successful businessman who ran various farms in Mamfé. He was popular in the area for being a great farmer and both he and his wife were local politicians. “In Africa, generally,” Patrick explains, “if you’re a businessman, you must belong to a political party for your taxes, or else you’re a dead man.”

His father’s success in the area must not have been too much of a surprise. The Bamileke people, his father’s tribe, have cemented their reputation as excellent farmers and businesspeople since the development of the cash economy in Cameroon and played a significant role as professionals, traders, artisans, and laborers.

According to The Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon, however, “While [the Bamileke] has become a significant factor in the national economy, their success has also generated some jealousy and resentment, especially among the original inhabitants of areas to which Bamileke migration has occurred.”

Owing to the patrilineal tradition, there was also an expectation for Patrick and his older brother to inherit the responsibility of the family business. However, besides that, Patrick relents that at home, they were not consciously raised with either Bamileke or Bakweri tribal culture.

“That is a big problem. I think my parents failed in that respect. For some Cameroonian families – teaching their children their tribal culture is the first thing. In Africa, elders from the village should pass those down to us…and they do, but my father – he was maybe only interested in his business.”

Patrick relents that other than French or ‘Pidgin’ English, he can speak his father’s language, but not his mother’s language. Everybody in their area in Mamfé, he says, speaks to each other in Pidgin. And Patrick always knew there was something odd about that. “Cameroon has 215 different dialects,” Patrick says. But today, the country rages at war over two foreign languages – English and French.

Of all the things that we have come to know him to be – friendly, easygoing, relaxed, resilient – Patrick often describes himself as “stubborn.” Perhaps one of the first times this revealed itself was in school, where he seemed to have been a bit of a troublemaker. While growing up in Mamfé, up until his secondary level, Patrick attended school in the Francophone region. While academics never seemed to be an issue for him – “I was a good mathematician!” He tells us and revels fondly in his stories about adventures shared with his many, many friends. “There was a time I always used to jump the gate to enter the class and get scolded for it by the principal!” Patrick laughs. “All my friends knew I had my own way.”

Maybe teenage Patrick was jumping the gate and tinkering with his fate too often. In 2007, 17-year-old Patrick’s mother, increasingly frustrated with his antics in school and at home, and his father, disapproving of some of his friends in Mamfé – decided to transfer Patrick from Mamfé to Buea, a neighboring village still in the Anglophone region.

Semblances of peace can be fickle. Cameroon is an ethnically diverse and culturally rich country comprised of over 26 million people belonging to 240 tribes, who can speak and identify with at least 250 languages and dialects. But since British Cameroons and French Cameroun came together in 1961, with the passage of time the foundation over which the ‘reunion’ was built has masked the growing discontent born from the marginalization of the Anglophones in schools, in the government, in the community – in Mamfé, throughout Southwestern Cameroon, and beyond.

2. Buea, 2007

Southwestern Cameroon (Anglophone region)

17-year-old Patrick had some growing up to do. In Buea, his father rented a room for him to live in, in a compound of 110 rooms. And for the first time, he was given his own mobile phone to use.

At the time, Patrick was nearing graduation from secondary school. But to live alone and independently for the first time, Patrick was terrified. It was a lot – to move from one’s childhood home, hometown, and everything one has ever known; and to leave behind momentarily the parents and family he so fiercely loved. He tells us, “But my parents always showed me they loved me, supported me, and that they were for me. The move was a big struggle for my mom, even if she was often so strict with me. Our arguments were like little wars!”

But then, Patrick’s mother was always on the road to visit Patrick – going from Mamfé to Buea and back again.

“I was scared, but there was a side of me that was so excited – finally, I thought, I am free like a bird in the sky!”

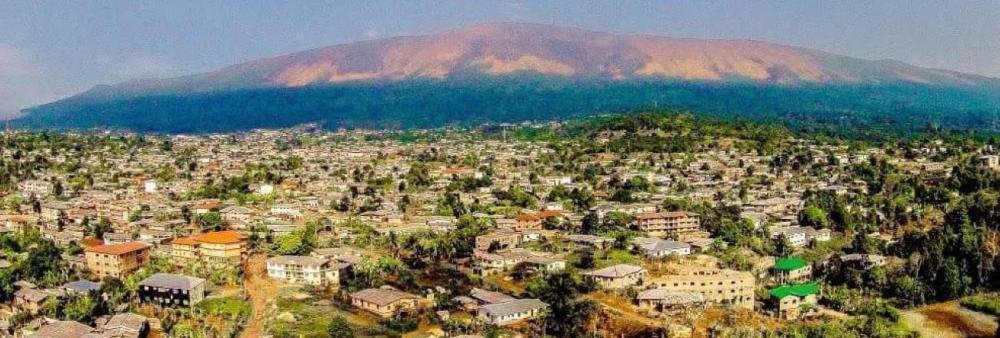

Buea is the capital of the Southwest Region of Cameroon, sitting gently on the southeast slope of Mount Cameroon. With a population of about 300,000, it is home to many university students given the number of higher education institutions in the city. It was a new, much larger city, brimming with opportunities and with so many undiscovered avenues and people for Patrick to meet and explore.

Patrick quickly makes many new friends in Buea. “For me, I can make friends everywhere. My friends from Mamfe stayed there. When I reached Buea, I made new friends.” These, he knows, would’ve been more to his father’s liking. “I got new friends, contrary to those I had before. These ones feared God, they were true Christians. I saw myself as a good Christian at that time too – faithfully going to church activities.”

Patrick’s adaptability, reliability, and keen ability to make friends wherever he goes are important assets of his throughout his life – but especially so in Buea. He quickly becomes recognized for it.

2.1. The Dubai Manager

Patrick begins a new chapter in Buea – with business. And rightly so, because Buea is also known as an administrative and trade center notably for textile, construction, and wood industries. There, you can find various remnants of Cameroon’s colonial past and palm and rubber plantations owned by the Cameroon Development Corporation. Buea was the perfect playground for Patrick’s first turn at business.

Since Mamfé, growing up with a love for animals, Patrick dreamt of being a great farmer like his father; to open and run a ranch – much larger than the farms his father owned – independently. Patrick was determined to go far.

“I was doing it before I realized it. I was doing business. I was doing it even while I was going to school – pursuing my dream of being a big farmer.”

He opened his first store in 2009. A young person himself at the time, he knew what was stylish, what the other people his age wanted. “I used to sell Adidas and Nike t-shirts – clothes for young people. Caps, trousers. I would go to Nigeria to buy these clothes, and bring them back for my store.” Patrick’s business expanded in a similar vein to his father’s. He had people working with him to help him import such clothes when he couldn’t.

He hoped to eventually expand his shop into something much larger, like Uniqlo. And with time, he hoped to start traveling from Cameroon to source goods from other countries like China or Turkey, to diversify his product range. “Back in Buea, when I started my business,” he remembers fondly, “people would call me the ‘Dubai manager’!” But by the end of 2016, Patrick was forced to close his store. People from his area began to flee from the protests, which were growing more violent.

2.2. The Anglophone Problem

Patrick was confronted with something else when he first arrived in Buea. “They knew me there, for some reason, as a francophone. Maybe because I had a group of francophone friends there.”

“I remember one day, when I was coming back home from school, there was a group of anglophones in front of my door. They asked me, when are you going back? I asked, where? They replied, when are you going back to your country? I said, I’m in Cameroon. I’m Cameroonian. And they told me: yes, and we are going to divide this country.”

Buea today is an important center for the Cameroonian population that identifies as Anglophone. Hosting Cameroon’s first anglophone university, Buea was the former capital of British Southern Cameroons and once an important stronghold of the colonial administration.

Patrick knows that many anglophones grow up with this mentality, developing a certain hatred against Francophones for various reasons, mainly institutional.

His startling encounter seemed to be a foreshadowing and a reminder of something stirring right there in Buea, in the heart of the anglophone region.

“The Francophones are proud – they don’t seem to mind the divide much really. But anglophones, sometimes in schools – some teachers and professors – when you hear what they’re teaching their students, you understand why there’s this hatred against the Francophones.”

The almost complete domination of Cameroonian public life by francophones has long been contested by the anglophones. Elite francophones have allegedly allocated resources for economic development in their favor, marginalizing Anglophones not only socially, but economically. For instance, hospitals, banks, and mobile telephone companies in Cameroon are predominantly francophone.

As Cameroon progressed further into its independence, leaving behind its colonial past, anglophone discontentment has grown with national policies, structures, and attitudes that have increasingly excluded them. National Entrance Examinations are conducted by the French Subsystem of Education, with a bias against Anglophone candidates; all five education ministries are francophone; all budget ministries except one are francophone; the general prioritization of French in state documents, public notices, internal government dialogue – and notably in leadership, with Magistrates in Southern Cameroon regions, school principals in Anglophone schools, and other government-appointed officials being disproportionately francophone.

Eventually, some could no longer hide their indignation. Anglophone dissidence is traced as far back as the mid-1980s when separatists began calling for the restoration of the Republic of Ambazonia. Some thought themselves being forced into being a quasi-colony of the French Cameroon state. Some cited the 1961 UN-imposed plebiscite for British Cameroun “independence” – questioning the only two options given, Nigeria or France, and the absence of the option for autonomous self-rule.

The feeling of many – that the Cameroonian population that speaks English, Pidgin English, or grew up in Southwestern Cameroon (the “Anglophone region”) are rendered unequal to the Francophone “rest” – would persist, dangerously.

10 years from then, in that same city where Patrick graduated from secondary school, started his first business, fell in love, and began his life as an independent, spirited young man – the Federal Republic of Ambazonia would declare its independence from Cameroon and claim Buea as its capital.

3. Mamfé Again, 2016

Things were starting to change in Cameroon by 2016. In December 2016, a letter was sent to Cameroonian President Paul Biya. It defined “The Anglophone Problem.”

The Anglophone Problem is: i. The failure of successive governments of Cameroon, since 1961, to respect and implement the articles of the Constitution that uphold and safeguard what British Southern Cameroons brought along to the Union in 1961. ii. The flagrant disregard for the Constitution, demonstrated by the dissolution of political parties and the formation of one political party in 1966, the sacking of Jua and the appointment of Muna in 1968 as the Prime Minister of West Cameroon, and other such acts judged by West Cameroonians to be unconstitutional and undemocratic iii. The cavalier management of the 1972 Referendum which took out the foundational element (Federalism) of the 1961 Constitution. iv. The 1984 Law amending the Constitution, which gave the country the original East Cameroon name (The Republic of Cameroon) and thereby erased the identity of the West Cameroonians from the original union. West Cameroon, which had entered the union as an equal partner, effectively ceased to exist. v. The deliberate and systematic erosion of the West Cameroon cultural identity which the 1961 Constitution sought to preserve and protect by providing for a bi-cultural federation.

The Anglophone Problem became something impossible to deny. That same month, protesters took to the streets after the French-speaking judges and teachers were appointed, by the predominantly Francophone government, to preside in Anglophone cities. Despite initially peaceful protests, these individuals were arbitrarily arrested by Cameroonian security forces. Strikes and riots throughout the region escalated into violent clashes with the police forces that led to several deaths, injuries, and arrests of lawyers, teachers, students, and activists who joined demonstrations. By the first month of protests, at least 100 were arrested.

International rights groups began pressing in, demanding urgent investigations of security forces’ use of unlawful, excessive force. In international news, the events in Cameroon from 2016 onwards would be known as the Anglophone crisis. In November, students of Buea University organized a peaceful march against the banning of their student union and the introduction of miscellaneous university fees. The police were called; students were brutally repressed, and some were arrested in their homes. Female students were “beaten, undressed, rolled in the mud, and one was allegedly raped.”

Watching behind his storefront in Buea, Patrick saw it all by the waves and waves of people who were evacuating the area, fleeing from the persistent signs of a coming war. The number of customers ringing his store would dwindle by the day. Eventually, Patrick had no choice but to close his business. So Patrick packed up and traveled back to Mamfé. He knew he had the option to work with his father’s farms. Given his father’s trust in Patrick and his knowledge of his reliability and business know-how, Patrick was appointed as supervisor of the family farms – his father’s eyes. Biding his time, Patrick was waiting to jump back to his own business.

“All of us saw the situation as only temporary.”

Everyone thought that the war would be just for a short while. A momentary lapse in life. “And after,” Patrick says, “the war would end and everybody, everything will start again, as it was.” But it doesn’t. It has not. The conflict – the Anglophone crisis, the Cameroonian civil war – continues, and spreads like fire throughout the country, transgressing the borders of language, life, of anglophone or francophone, former British Cameroon or former French Camerouns.

By 2017, Mamfé would become the frequent battleground between the Cameroonian Army against Ambazonia Defence Forces and other separatist forces. And the year after, conspirators would set fire to Patrick’s family home. Patrick would begin a long, difficult journey, running for his life and his freedom. And he has not stopped running since.

“Sometimes people would see you as either – francophone or anglophone – while you were growing up in Mamfé, Buea, Douala. But how do you see yourself?” Patrick never falters.

“I see myself as a Cameroonian. To say that I see myself as an anglophone only is to reject my father. To see myself as a francophone only is like telling my mother: get out. And English, French – those are not even our languages. All I know is that I am Cameroonian.”