“How will we survive?”

1. Temporary Release from the Detention Center

1.1. Challenges and Expectations of Karihoumen

On the 28th of May 2022, Sana was finally released from the detention center. To get to this point, Sana had to apply for karihoumen. This is a status that allows the detainee to live outside the detention center and stay in Japan temporarily. A provisional release is specific to Japan and could be compared to bail. There are no set standards for granting or denying provisional release, but the Japanese immigration services state it is given if a temporary release is found necessary for detainees with “health reasons.” However, there are no set standards or criteria, making it difficult for detainees to know whether or not they will be granted karihoumen.

First, Sana had to go through a lot of challenges such as finding a sponsor and a lawyer. As a foreigner as well as a refugee, finding someone you know and trust is difficult in an unfamiliar country. His trust had been broken before, but Sana kept his hopes up and remained determined to get out of the detention center. He called his brothers, other relatives, and any person he knew living in Japan to explain his situation. This did not go without its difficulties, as calling someone from the detention center is extremely difficult. Asking for a phone call, Sana had to convince the guards: “They [the guards] said they will not give me, so I try to talk to them, because I told them it was important.” Sana managed to convince them, but it did not go comfortably. He continues to explain, “They have to take me to a room. Then they will, like one will be standing behind you, they will check and take a sheet of paper and give you to write the name you want to write and they’ll take it back.” The guards “are keeping the phone,” and control who is allowed to call and for how long. “One will be standing behind you, they will check,” Sana emphasizes.

Fortunately, Sana was able to reach out to some family members all over the world, who then also called other people they knew, including a family relative who was in Japan, whom he contacted. “I called her and I explained everything. She didn’t even know that was in detention. So it was so shocking.” She was so shocked by his experience in the detention center and wanted to help Sana. She asked her brother, a permanent resident in Japan, if he could support Sana as a guarantor and he agreed. This man was able to help Sana by pleading to be responsible for him and taking care of him while being released. Finding a guarantor and lawyer for provisional release is extremely important, as they are requirements for the permit. However, it is also difficult.

Finally, after two months, his application for karihoumen was approved by Japanese immigration. This is certainly not easy; requests for provisional release are rejected with increasing frequency and 80 percent of detainees’ applications have been rejected at least three times. Detainees need a deposit, a lawyer, and further payments. Sana thus had to pay a deposit of 200,000 yen and was lucky to have his guarantor and lawyer. The reason for the approved release was his health issues, which is a common reason for being released, especially when the pandemic hit Japan. Releasing detainees was seen as a strategy during the pandemic to make sure the detention center would not be responsible for the possible death of detainees. This strategy was “treacherous” but also “brutally effective,” as detainees would happily accept leaving the detention centers, while they actually continued struggling to survive on the restrictions of karihoumen.

1.2. Reality of Karihoumen

Feeling relieved and excited, Sana expected to feel free again; he explains, ”I felt relieved and so excited because I go have like peace of mind and I could move freely,” However, the reality was different. He continues, “What I was expecting was different because you cannot even use karihoumen to go to the hospital, even to register your apartment to go to the city office. They said it’s not recognized.” Disappointed and frustrated, Sana experienced how karihoumen come with a lot of restrictions. Under this status, one cannot work, open a bank account, access health insurance, or even move freely in the country. “I’ll try to open a bank account. So that they can send me money from other countries. They said it’s not, they cannot, and we cannot use karihoumen… So it’s like just nothing,” Sana explains. Japanese officials also decide when and if one can go outside of their prefecture. When Sana wants to leave, even for one day, he has to go to the immigration office to apply for permission. “You have to apply some kind of note and tell them the reason why you’re going there to do this. And the person you’re going to meet… has to be called to confirm. It’s too stressful,” he says as he shares the frustration with us. This needs to be done at least a day before, and the process may take several hours, which Sana finds even more stressful.

“Especially when I want to do some things and I have to travel to a different prefecture, I feel so depressed.”

To make things worse, with this type of status, one has to go back to the immigration office in Shinagawa every one, two, or three months to get the provisional release extended, as the premise of the permission is temporary. The Japanese officials decide on the number of days one gets, and at any time, they can decide not to allow a renewal. Thus, people living with this type of status in Japan constantly have the possibility of being detained or deported hanging over them. The reasons for detaining again after release are often arbitrary and unclear. For example, Louis Christian Mballa, a 40-year-old Cameroon-born man, was detained again on the grounds of gaining weight and Majid, a 51-year-old Iranian man was detained again with the officials not even giving any reason. Asylum seekers are either granted permission for residence (such as the Designated Activities visa, or the refugee status which is granted to less than 1% of the asylum seekers in Japan) or deported and/or detained at some point.

Sana is also influenced by the uncertainty of the length of karihoumen and how often he has to go back. In December 2022, Sana’s permit changed from three months to one month, so he had to come back every month from then onwards. He says they did not even explain why: “Nothing, just like that…they don’t tell you the reason why. They just make their decision.” Waiting anxiously for hours at the immigration office, Sana fears that anything can happen. He explains, “Sometimes they can even, some people will go and they say they will not renew it for them. So either they’ll go back or they’ll be detained.” The officials may tell Sana next time he has to come back in three months, two months, or one month, or he might be taken up to the detention center immediately. “They never give a reason,” as he says, so he cannot predict what happens. This causes him to be stressed and depressed.

Although Sana’s mental health improved after getting out of the detention center, he does feel influenced by these restrictions that come with karihoumen. On the day of the interview, Sana felt depressed. He is especially influenced by not being able to work and having limited freedom of movement. While he is no longer physically detained at the facility, he is still encaptured by the restrictions of karihoumen, and by the borders of his prefecture. His situation makes him unhappy, but he says he does feel better compared to the detention centers. He tells us, “Because what they were doing, they were not just helping at all. It was just damaging…You are suffering…and they are giving you medication that is not for stomach.” He continues, “I was so happy that I could just get access to medication by myself. Anytime I feel pain, then I can go to the hospital at any time.”

2. Survival

2.1. Wanting to Work, but Not Allowed

“Only foreigners would without visa can do it. And they do it just to survive.”

While many people with the provisional release permit want to work in order to live and survive, they are not allowed to. Paradoxically, Japan is facing an enormous shortage of workers, from 1.21 million in 2017 to an estimated 6.44 million in 2030. The employment of foreigners, among other groups, should be encouraged to address this scarcity. Another benefit of employing more foreigners is that the Japanese government could receive more tax money and maintain its global economic position. For these reasons, it would be logical to welcome new workers into the country. Some changes happened under former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration, where some foreign workers were accepted under a specified skills visa. Nevertheless, the Japanese government continues to deny visas to many immigrants, does not allow people with karihoumen to work, and does not accept a lot of foreigners to stay and work for a long time in Japan.

As a result, most asylum seekers on karihoumen are forced to work illegally to survive, especially in industries where many Japanese people do not want to work. In the 90s, “illegal” workers were doing the bottom-rung paid, dangerous, and difficult jobs that Japanese people avoided, known as “3D” (Dirty, Dangerous, and Difficult), jobs that often do not provide a contract, health insurance, or proper safety standards. As these workers are desperate for jobs, they are often unable to speak out about issues and find it difficult to claim their owed wages. Moreover, if they get injured, they will probably get fired instead of receiving help, and going to a hospital will be expensive as they do not have health insurance. Many workers further avoid the hospital at all costs in case anyone finds out they were working illegally. Someone Sana knew with karihoumen worked illegally as a mover and got injured. He explains, “He went to help one guy to clear his place and there are metals, metal parts that they need to pick. So he picked, it was too heavy and he couldn’t lift it by himself. He told him to wait and someone will help him to lift. So he lifted by himself, but he dropped it on his toe. And it was so much, now he cannot work properly more than I think three weeks. So he’s just home like that…He don’t want to even go to the hospital…So went to the pharmacy.” As Sana always has been an activist and a kind helper, he helped the man with visiting the pharmacy for medication and bandages. This man did not want to go to the hospital “because of money. And also scared, like if they’re asking what happened to him, he went to work and this happened to him.”

“It’s just to make life so complicated and so difficult for us to live.”

While life in the detention center is made extremely challenging and tough to ensure that no one wants to stay in Japan, life with karihoumen is made challenging by having to survive while not being allowed to work. As Sana points out, the Japanese government seems to think if asylum seekers were allowed to work and get paid, they would want to stay in Japan. Thus, they make lives for asylum seekers extremely challenging, just to push them out, and keep them out. This strategy of “self-deportation,” which includes removing the ability to find employment, is a removal strategy of making life so unbearable for a group that its members will leave a place. Japan’s policy around karihoumen certainly pushes for restricting detainees’ lives, making life “so complicated and so difficult for us to live,” as Sana puts it. Another aspect that makes life in Japan challenging as a temporarily released detainee is not having health insurance.

2.2. Health Issues, but No Health Insurance

“I wish I could get insurance,” Sana expresses his frustration as he has to pay more than the regular 30% of the medical expenses on karihoumen. He continues, “I remember last year I had bone nano biopsy, which maybe insurance people pay like 30,000 [yen], but they made me to pay like 100,000. Yeah. 100,000. Yeah. it is because I was not having insurance and no visa.” On top of the financial burden, Sana also experienced difficulties at the hospital due to language barriers on top of not having health insurance.

As a foreigner and refugee, Sana experiences frustration and discrimination at the hospital. Especially, without health insurance and a Japanese residence card, filling out endless forms at the hospital is part of the difficult experience. When you are in pain or need medical help quickly, this can be even more stressful. Besides, being able to communicate your issues and symptoms properly is essential so you can receive proper care and the right medication. Sana notices how some workers at the hospital do not understand, or pretend to not understand the language. “It’s so difficult sometimes you even visit the hospital because you don’t have any insurance, you be treated differently. So it’s so bad, so difficult,” Sana voices his disappointment. All of this counts up to more frustration, stress, and feeling like an “other” in Japan.

Fortunately, Sana was treated for his illness at the hospital and got proper medication after getting out of the detention center. This was desperately needed as the health care inside the detention center was extremely problematic. Other detainees have accounted how they would only receive paracetamol when they needed more serious medication. Since 2007, 17 foreign nationals have died in detention centers across Japan.

Without a job, refugees have to survive on money from the state, which is never enough to live safely and comfortably. Sana has to rely on his siblings, refugee organizations, and volunteers for financial aid and hospital visits. He describes it as “stressful” and “embarrassing” to keep asking for help, and sometimes “they cannot continue helping you, they be tired…So you, you’ll be suffering.”

“I feel so bad to ask people for help.”

All provisionally released detainees must rely on relatives, NGOs, or Japanese officials who are willing to help them survive. Without their help, Sana simply questions, “How will we survive?” Life thus is extremely difficult for refugees on karihoumen in Japan; as they cannot work or get health insurance, and simply surviving every day is a big concern.

3. Identity in Japan

3.1. Discrimination: “They Just See You and Try to Discriminate”

“They think like you are criminal, you committed crime and they send you to prison.”

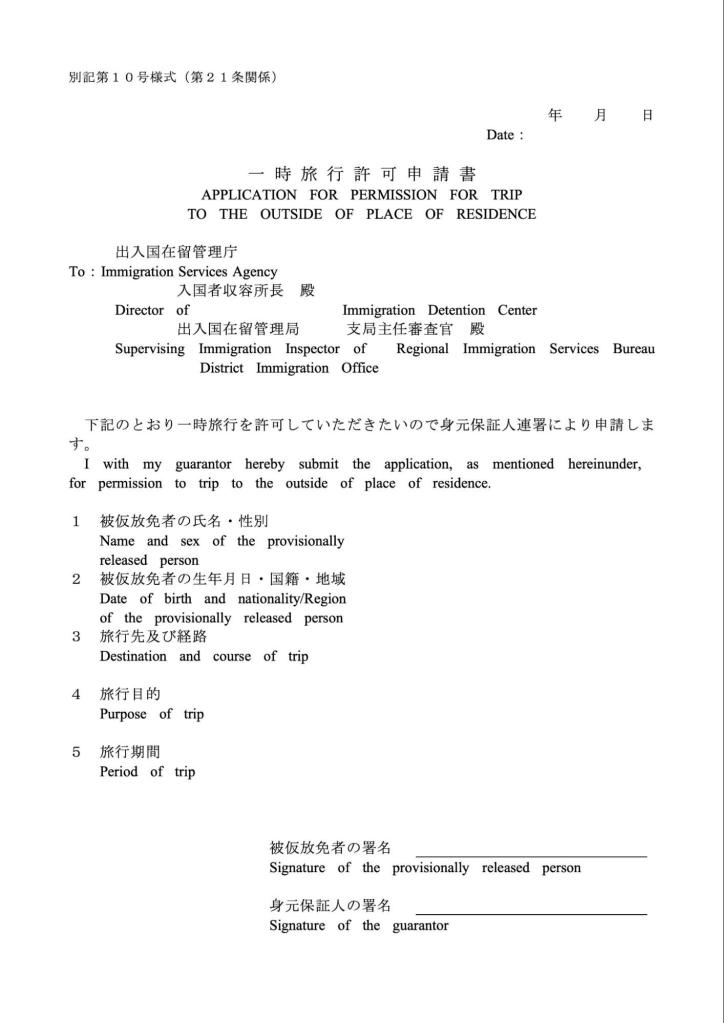

The provisional release is not only given to refugees but also to criminals. The document looks the same for both groups. This is because the detention center houses both refugees and inmates whose trials have not been closed. Sometimes, Sana is seen as a criminal by government officials, the city office, or other organizations. This makes his life more difficult, as he says, “When you even talk to them and mention about, they don’t even want to listen.” Thus, firstly, Sana is discriminated against because he is seen as a criminal through his provisional release document. Secondly, when he tries to explain this, the officials do not want to listen to him. The reason for this is that refugees are often distrusted. In Japanese society and beyond, refugees are often seen as “fake refugees”: immigrants, often presumed illegal, who apply for refugee recognition when they are not refugees. When asylum seekers apply for refugee status in Japan, they, including Sana, often hear how it “is not just like under the category of refugee recognition status. And, when you ask them what kind of claim should be under their recognition status, they don’t even say.” The UNHCR defines a refugee as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” Sana tells us, “When you try to check under the UNHCR…your life is in danger and you feel that you persecuted, but they don’t care even providing your evidence. They don’t get scared.”

“So devastating, sometimes you actually speaking the truth and also telling the real story, but yet they don’t really respect it or they don’t really believe in whatever you’re saying.”

Being a refugee in Japan thus can mean being seen as a fake refugee who is only looking for economic opportunities or even a criminal, who is not to be trusted. The Japanese public has been reported as sometimes having mixed feelings toward foreign nationals, especially those seeking permanent residency. For instance, some Japanese people are worried about the deterioration of social order and an increase in crime rates due to the influx of immigrants.

Additionally, In Sana’s daily life, he is cautious about where and when to walk around, due to his previous experiences of racial profiling by the Japanese police. Before going to the detention center, he was shocked at how the police treated him. Now, he still sometimes gets stopped by the police, which is extremely anxiety-inducing and shameful. The possibility of getting detained again, where he suffered “psychological torture,” is ever-present. His skin color means that he is stopped more often by the police. Foreign residents in Japan, especially black people, have noticed police brutality and racism on the streets.

“When they see you being black person and when you’re walking during the daytime, they can just suspect you.”

One instance of being stopped by the police was last year in winter when he went to the Ghanaian embassy. Among a crowd around a train station, he was picked. This story shows the systemic issue of racial profiling in Japan, although it is important to note that racial profiling by the police is a worldwide problem. Racial profiling occurs when law enforcement officers decide based on a dark skin color that someone is involved in criminal activities. This has been reported to happen to 63 percent of foreigners in Japan in the preceding five years. While foreigners on provisional release may be seen as criminals or fake refugees, foreigners with darker skin tones are often treated with racism.

Sana experiences discrimination as a Muslim in Japan as well. “Some people, because they don’t know about the religion, they only hear like a Muslim and they think about how the world has painted Islam,” he explains. Globally, Islam has become associated with terrorism, especially since the events of September 11, 2001. “Illegal” migrants who looked Muslim came to be seen as terrorists all over the world. In Japan, Muslims are a religious minority and they are often not met with acceptance. Ideas of terrorism are discriminatory and there is no indication that the Muslim population in Japan is radicalizing or that they would pose a threat to Japanese society. Nevertheless, these ideas persist in Japan, as Muslims are also subjects of racial profiling in Japan. Thus, Sana’s identity as a black Muslim refugee influences his experience in Japan, where officials do not always listen, the police may stop him, and some people avoid him only based on his religion.

3.2. Faith: “Thinking About God, I Just Feel Calm”

Religion plays a big role in Sana’s life and continues to do so in his life in Japan after getting out of the detention center. At first, he lived in Chiba where it was difficult to pray, find other Muslims, and have access to mosques. Sana recalls, “You have to just pray by yourself so you don’t feel the unity. You always being lonely by yourself.” Now in Saitama, he says “I found like many Muslims around and…there are also Christians around that we can also just like associate ourselves and socialize. It’s so like good, so good for me.” Practicing his religion together with others is important to Sana; it gives him a sense of unity and battles his feelings of loneliness. Mosques in Japan contribute to community-building and support Muslims like Sana to feel connected to others.

Praying to God helps Sana to cope with his problems. “Like today I was so depressed and so worried, I don’t know what to do. But after just maybe just sitting for some 30 minutes and thinking and thinking about God, and I just feel calm and I feel determined no matter what. You just have to have hope and courage. You will, you will make it so it’s not the end of the life,” he shares with us.

4. “Soft Heart”

After fleeing his home country, arriving in an unfamiliar country, being locked up in the detention center, and now surviving with karihoumen, Sana still commits to his activism. As Sana’s childhood was shaped around helping his parents, his whole life has been filled with helping others. His father always told him “to be kind and to be helpful to anyone.” Sana puts his teaching into practice. He says, “Even when I was young, I always take care of them…So I always want to help out. So I go, just get up and leave my home and go to some places just to help someone and stay there like two days, three days, then I come back home.”

“I have like this kind of soft heart, so if I see someone in pain, I don’t feel happy.”

For example, Sana helps fellow detainees with getting lawyers. “They were finding life so difficult, so I tried to contact some organizations and lawyers and I was able to get some lawyers to help them,” he explains. Sana also got some volunteers who could speak French and English to go to the detention center to visit detainees to help them with getting out and finding their housing. Another time, someone Sana knew got seriously ill and had to go to the hospital immediately. He and a friend of his, Nanu-san, helped this man with getting money from two organizations so he could get the surgery he needed.

Getting out of the detention center helped him spend time meaningfully and regain a sense of self, the Sana he was back home. “I just enjoy like empowering people and helping people out in need,” he tells us. From the trauma of escaping home, the psychological difficulties at the detention center, and the hardships of karihoumen, he copes by helping others.

5. Sana’s Future: “If It Is Very Tough Today, Maybe Tomorrow Things Will Change”

“There’s hope and there’s still blessings to come.”

One day, Sana wishes to have a family of his own and be an example for his children, just like his father was for him. He elaborates, “I just want to continue doing what my dad has done. And he was, let me say, he was like a prominent person in the community. I also wish to be like that.” His father’s and aunt’s business was also an inspiration for him; he describes, “I wanted to also be a businessman like my dad. So I want to be able to establish my business here. And I can buy things from Japan and ship to Africa. Like my auntie’s business…She has contacts with like South Korea, Singapore.”

Nevertheless, Sana first needs to get a visa that allows him to stay and work in Japan for a longer time. “So if I have a stable life in Japan, like having my visa…that is what I’m dreaming of, like doing,” he voices his hope. This will be challenging as Japan has low acceptance rates for refugees, but Sana remains hopeful: “Sometimes we think that things will not be possible when in the end, and then it makes possible.”

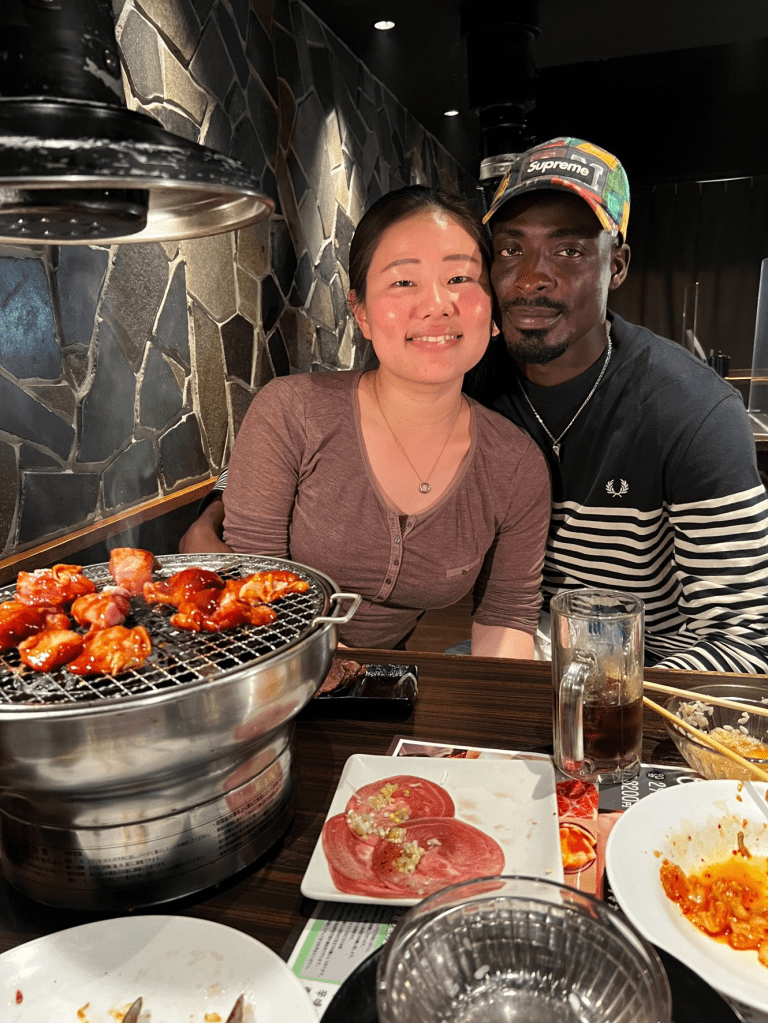

Something Sana always dreamed of was establishing a family in Japan, and now, he has a fiancée here. “I was having my dreams of having family here, yeah, I will stay here,” he shares happily. He hopes to simply have a peaceful life and says he would want to visit home to see his family one day with his own family in Japan.

Sana’s future is filled with hope: hope for peace in Ghana and Burkina Faso, hope for a family, hope for a trading business, hope that “no condition is permanent,” hope that he will be back in Ghana and Burkina Faso one day, and hope for change in Japan.

“When it is hard today, it can be easy tomorrow.”