“I am inside the immigration center, so I talk because I’m free to talk.”

Table of Contents

- The Day He Was Detained

- Inside The Detention Center At The Tokyo Regional Immigration Bureau

- Leading The Strikes And Speaking Out

- Coming Out Of The Detention Center

1. The Day He Was Detained

“Talk to me straight that today you are going to detain me, don’t say this this this… because I know everything.“

2. Inside The Detention Center

At The Tokyo Regional Immigration Bureau

Sunday was an influential person even inside the detention center. He was a source of information and a leader. Inside the building of the Tokyo Regional Immigration Bureau in Shinagawa, regular immigration procedures are underway on the 1st floor. However, there are a number of people locked up in the same building, but on the upper floors which is not open to the public. This is the place where people are taken to be detained. Official information about the detention center exists, although the details are clearly limited. These enclosed upper floors are divided into several blocks where interactions are not possible. Many people live together in separate small rooms and need to share the facility with only basic things for living within each block.

Usually, they share a single room with 7-10 people from different countries having various cultural or historical backgrounds. There is a playground that Sunday describes as an “enclosed type of playground” where he sometimes used to “warm up and do small exercises” to keep himself healthy. “Sitting or sleeping” for a long time inside the facility is “sometimes dangerous” for many detainees packed inside the small space. Staying in a limited space with a lot of people for a long period results not only in causing physical problems but also in putting psychological burdens on them. The stress burden was at the level where according to Sunday even the immigration officers whose job it is to inspect the detainees were “also detainees” and “they [we]re stressful much” to the point Sunday “used to hear them shouting too much,” because “they [we]re always inside there, even if they move outside”. He views detention as another form of torture that will drive people to a corner by cracking up peoples’ bodies and minds eventually to deportation.

Without any privacy, people can get very stressed and some fights can happen over very little things. “We need[ed] to become family,” mentions Sunday, despite the situation he was in. “I used to talk to them to accompany, because some people they come in and they fear,” he said by pointing out the necessity and his ability to encourage those who cannot handle themselves with the stress from fearing deportation. Thus he used to inform and encourage others to write an application form for the visa or status to get out of the detention center because many of the people inside either feared or did not know what to do other than being detained. He knew that at least what the detainees can do or are allowed to do while kept inside was to fill out the form for a visa or a status, although the acceptance rate was low. Some detainees were encouraged by Sunday and more people started to ask the immigration officers for the application form. Having been a leading figure back in Uganda, Sunday showed good leadership among the other detainees around him. The immigration officers did not like Sunday telling others to apply for Karihoumen status and warned him that “he is not the master of this place,” perhaps because the officers did not want to have additional work or activities to deal with. Then Sunday would reply, “What am I supposed to do?”, because talking about whatever he sees to make changes is what makes Sunday who he is. By informing others using his knowledge of the immigration system and procedure in Japan, Sunday positioned himself as an influential leader who would make changes to many people captured in the systematized unjust structure of the Japanese immigration policy.

“This should not be like a prison, it’s just a detention.”

Sunday’s perception of the detention center lies in his belief that “this [should] not [be] like a prison, it’s just a detention.” This principle had always been a key that moved him forward and made him think the immigration system’s orders inside the detention center were restricting him against his value to express and do what he believes is right. According to his experience of being arrested and tortured in Uganda just for expressing his political will, Sunday thinks that the detention center that stops him from what he does and what he believes is right could be as same as a prison because both of them “stop you from what you are doing, and they keep you there.” Thus whenever he tried to acquire his value to inform others about the unjust immigration system, he would confront the immigration officers that “one thing you can do, if you deport me, that’s a different story, which you cannot do” until “actually [the officers] fear for [him] to fight even.” That is when Sunday feels himself being treated with dignity as a person because he can be a leader who would make changes and stand above others including the immigration officers to mobilize the surrounding situations.

Sunday wanted a change. By this time, he had not only been told to stop helping others by providing useful information but also been restricted or ordered what he could do, know, and eat. He needed a change for what he was limited to having access to, and Sunday knew well that he had to. However, knowing that the Japanese immigration system works only through the orders of the boss, he made the rational decision to directly contact the boss.

Sunday had several points he wanted to make clear and ask the boss.

Here are some examples:

- Interminable Detention

- Restricted Food and Poor Medical Care

- Poor Sympathy

- Payment to Get Out

- Limited Freedom of Movement Outside the Detention Center

2.1. Interminable Detention

“How long do you want to detain me or punish me in this situation?”

Sunday felt it was not fair that the detained people are not told when they could be released when he argues that even the prisoners are told in advance of their term of imprisonment. Interminable detention is a punishment as it is mostly long-term detention and it holds back both the detained people and their family members to plan their future which increases the level of stress and anxiety. Fundamentally, when immigration understands the fact that many detained asylum seekers like Sunday are never going to get deported from Japan, prolonging the detention period even makes the act of detaining these asylum seekers to be pointless. In addition, since most asylum seekers end up getting the Karihoumen status instead of the refugee status, the series of restrictions they face are more or less the additional unreasonable punishment, which will also be discussed in point 5. below (5. Limited Freedom of Movement Outside the Detention Center). Thus for Sunday, it is hardly understandable why immigration continues to make pointless extra detention for him.

Recently, a news article reported that a new proposal was revealed at the government panel to discuss the issue of long-term detention in response to the increasing incidence of suicide attempts, self-harm, and growing calls from experts, supporters, and detainees like Sunday. However, the panel discussion seemed to shift to “rethink” to strengthen the penalty, only to kick out foreign residents in Japan without sufficient lawful status, such as the asylum seekers on Karihoumen waiting for refugee recognitions because of the unclear and unjust current immigration regime. At this point, although the need to find some alternatives to long-term detention is addressed, there is not much improvement done to find a better “balance between supervision and support,” which is as harsh as punishment for many detainees inside not knowing how long the situation will last.

2.2. Restricted Food and Poor Medical Care

”Why do immigration stop us, stop us from eating banana? It is even we bought, we bought it and it’s expensive with our money.”

The food provided by the Japanese immigrants was of poor quality which made Sunday feel that “I can’t eat, why I have to eat this” because the food such as “two eggs, two meat, and some bread” were “cold,” and those bland food were low in quality as much as they “made [him] not for a human being,”. Some detainees like Sunday have some money “used to buy some banana[s]” with one’s own money, however, those who cannot afford to buy can starve or become malnourished. In fact, there have been several cases reported in which the detainees claim that an example picture of the poor quality food provided by the Ministry of Justice is significantly different from the food they actually eat.

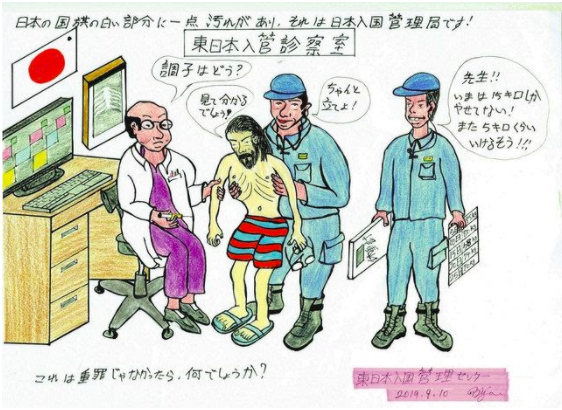

“They are not even nurse[s] or doctors, they are just maybe officers who didn’t know what to do, they just give you drugs, you take the drugs and that’s all, they don’t care.”

When Sunday was sick, he was always given the same medicine for a few weeks even if he had different symptoms. He mentions that if one person’s “sickness is serious,” they “just take him to some hospital, and maybe not a good hospital,” which is possibly worse than the clinic inside the detention center because the detainees have to be tied to handcuffs. This is not only the case for Sunday, and it is reported by many other detainees that painkillers are the only drug given to them after waiting for an appointment to see the doctor which takes several weeks. It is easy to imagine that not being able to access medical care when being sick and weakened is an action that violates basic human rights. This poor medical care reflects the systematic feature of the uncaring and indifferent Japanese immigration system.

2.3. Poor Sympathy

“I will stay with my disease, because if you put one of this(handcuff), maybe I get my memory(of persecution) back.”

Sunday thought that the immigration rules neglect detainees’ will, and never learn from them. Whenever he was about to be taken to a hospital outside the detention center, he suffered from flashbacks of persecution. Other than that, countless interviews he has taken part in for years where Sunday has to answer the many questions that provoke his memories of his traumatic past. “Then what evidence do you want me to produce, the one after my death occurred?”, in which he questions the poor understanding of how emotionally hard it will be for him and that he presented all he had of himself as proofs other than the death, the last thing he could possibly offer.

The lack of sympathy is also from the arbitrary decisions made by the Japanese immigration process that hugely depends on the unpredictable orders by the boss of the Immigration Bureau. Not only Sunday but also according to Ushiku no Kai, most detainees who apply for Karihoumen status experience rejection without any reason. It is an endless cycle that seems to continue as the decision is dependent on the boss that does not directly contact the detainees which makes it impossible to have sympathy for the detainees. Whenever suicide cases and self-harm incidents were reported, Japanese immigration stated that there was “no relation” to the detention system itself, which is a problem that ignores human dignity.

2.4. Payment to Get Out

“[The immigration] asked a payment of 100,000 yen, it’s not bad but in my situation is bad.”

Sunday questions why detained people are asked to pay quite a large amount of money, a deposit to go out when the immigration bans them from working. He wanted to ask to reduce the amount as much as possible because, for Sunday and many other detainees, his friends and some NGOs’ financial support were needed and used for the payment. Also, a guarantor who lives in Japan is required for every detained people to get released which is difficult for many people. It is difficult for many detained people because getting a guarantor is extremely difficult even for Japanese people. Guarantors have a huge responsibility for the payment, which is also about building trusting relationships. Still, many detainees would find it hard to find a person whom one can ask for that much responsibility. Considering the fact that many asylum seekers who aim for refugee recognition inside the detention center are captured and forced to be detained by Japanese immigration, the orders that ask for these payments are incomprehensible.

2.5. Limited Freedom of Movement Outside the Detention Center

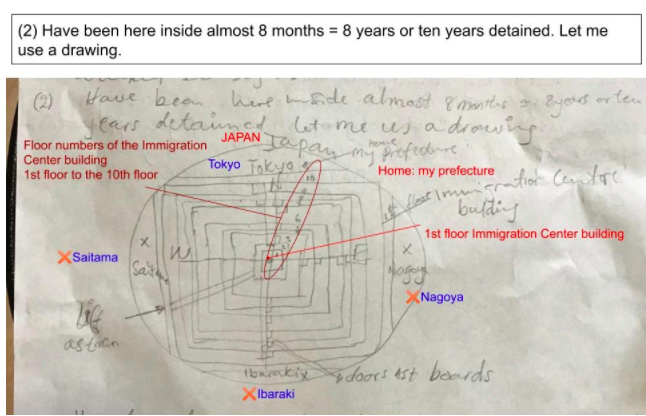

Of course, people inside fill out a form to apply for the Karihoumen status to get released from the detention center as soon as possible. Sunday was indeed one of them too. However, here, Sunday is making a larger point on why he believes that being detained and getting out of the detention center yet living on the Karihoumen status is the same in the sense that they both limit a person’s freedom of movement. This is in fact a rational point to address when looking at the unjust structure of the Japanese immigration policy.

“I didn’t know when I am going out, and even if I am out, I am not supposed to do anything, how do I survive?“

The point and the drawing below are an embodiment of how he thinks that living with Karihoumen status but without a visa can be considered as limiting one’s freedom of movement which is equivalent to being inside the detention center.

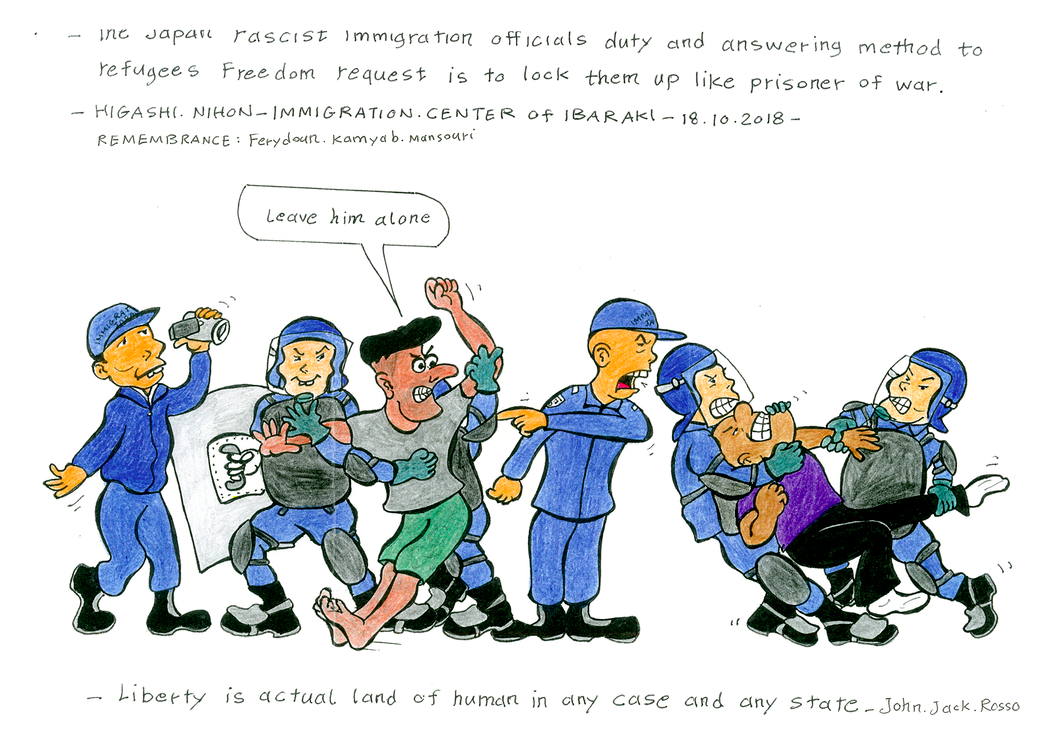

3. Leading The Strikes And Speaking Out

“[The immigration officers] stop you from eating banana, you are going to die here, inside, so I tried to convince them to, maybe to make a strike.“

“I was surprised, the day they come and they are going to meet the boss, and they take me to the hospital.”