“You have no choice. In that situation there’s no discussion, you just leave.”

Uncertainty, cruel irony, survival, patience, change, and adjustment – Yasser’s experiences after fleeing Syria were underlined by factors that permanently altered the course of his life. Yasser was forced to undergo the transition from a carefree English Literature Major at Damascus University who had a passion for soccer, to losing his house to a bombing, to having roughly no means of survival and having to forget himself and his personal goals to provide for his family. Yasser was left with no choice but to leave the only life he has ever known to ensure his and his family’s survival.

Table of Contents

- Experiences in Egypt

- Layover in Lebanon

- Journey in Japan

- “The first six months in Japan was the worst period in my life.”

- “When we came to Japan, we had zero, we had nothing.”

- “The first seven months we felt like, ‘OK, get out of here’.”

- “You need to prove that if you go back to Syria, you’re in danger.”

- “After seven interviews, she gave a lot of information, and I think because of her, we got the status.”

- Refugee Recognition

1. Experiences in Egypt

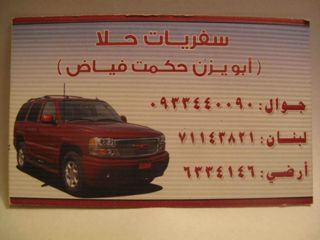

Being forced to leave one’s home is a fate no one wants for himself. But with their house turning into dust, Yasser and his family were left with no choice but to flee their comfortable life in Syria, and within two days, collect all their necessary documents, pack their important belongings, and head to Egypt in search of a new life. They found a contact who booked them a shared service taxi–an SUV that carries those wanting to leave Damascus across the border–to Lebanon where they flew to Egypt.

Thrusted into a new life–a life he did not choose for himself–Yasser became a refugee.

Upon arriving in Egypt, an Egyptian acquaintance of Yasser’s friend in Syria rented them a house. But at age 21, when the only life you have ever known is one of stability – one where your financially stable parents are capable of providing you all your needs and wants and one where your only worry was who among your friends was coming to play soccer with you after school, what time your mom was getting home from work, or which reading you were supposed to do for your English Literature homework – nothing has ever come close to a change of lifestyle as drastic as this.

From the big housing complex shared with his family and relatives that he lived in Damascus, Yasser was uprooted into the slum areas of Egypt. Its dirt is unparalleled to anything Yasser has ever seen before.

The seeming 180-degree change in lifestyle was unbearable. Yasser and his family tried to stay in the house for three days but could only endure too much of its inhabitability. With trash, dogs, and cockroaches disrupting their daily living, they were more than determined to move out of the place, whatever the cost.

1.1. “Get us out of here. Whatever the price is, whatever money you want.”

Yasser and his family then decided to move to Madinaty in Cairo. Madinaty was a new area that Yasser says is “a bit fancy, more expensive, but well-guarded and well-organized. It’s kind of a closed city with guards in every building and everything, it has just 2 supermarkets and you move around by small buses, but it’s safe so we moved there.” This sense of safety is their number one priority because it was only days prior when Yasser’s house was bombed putting his and his family’s life at risk, and he says that the least that they can do to cope with their swiftly shifting realities was to live somewhere decent.

1.2. “After being in all that situation, the least you need is some safe and clean place to live in.”

On top of the Madinaty neighborhood having a considerable physical difference from their initial neighborhood in the “slums” of Egypt, the price to pay likewise presented a big dissimilarity, with rent going upwards of 7,000 EGP/month (49,000JPY as of October 2021). But Yasser and his family were not struggling financially. Oftentimes, refugees are stereotyped to be people in camps or boats risking their lives with barely anything to get by; portrayed in impactful videos like this. While those circumstances do depict the reality of a refugee’s journey, it does not encompass every refugee’s experience–the refugee experience is not binary and their struggles are not patterned. Yasser, for instance, despite having to move their entire life, had the ability to live comfortably, leaving Syria with his mom’s savings and with his dad still actively working as a professional chef in Qatar, sending them money so they could rent a house and live comfortably.

Yasser’s dad was not the only member of the family who lived and worked abroad: he has family in many places around the world, working and sending remittances back home. One of these many family members is his uncle who resides with his Japanese wife in Japan, who heard that Yasser’s family had fled Syria and was in Egypt. His uncle and his two daughters–Yasser’s Japan-born and raised half-Japanese cousins–came to visit them in Egypt on holiday. Living leisurely and trying out the different kebabs in Cairo, Yasser’s and his uncle’s family lived in a big house together for two months.

It seemed like everything was working out like a refugee’s dream–Yasser had now adjusted to their living situation in Egypt; having left the ‘slum’ areas of Egypt and achieving his initial goal of finding a clean and safe place to live in. But just as he was about to embark on the next step after adjustment–assimilation–reality had come creeping in. Despite finding a safe and clean place to live in Madinaty, life in Egypt was not at all sustainable because Yasser could not do anything there.

Yasser tried to start a new life in Egypt. He applied and submitted his documents from Damascus University to continue his education at an Egyptian university, but they rejected him. He tried to look for a job, but he was unsuccessful either. He explains that this was because of Morsi and Sisi problems in Egypt, “It was the time when the coup was launched on Morsi, between changing Presidents for Elsisi to come and there was a lot of troubles similar to Syria.” Because of this, Yasser had virtually nothing to do in Egypt, “for that seven months, we were just kind of surviving,” he says. Although their living situation in Madinaty was desirable, a life of constantly trying to survive on a daily basis was not sustainable. “In Egypt, nothing worked out. Not university, not work, nothing to continue my future.”

1.3. “We can’t do anything here, there’s no future here.”

“In Egypt, nothing worked out.”

Yasser faced a cruel irony: he found a clean place to live in, a place he could afford with his father’s financial help but; he could not start a life because going to university or working was impossible. So, Yasser and his mom had to make the decision–they had no other choice but to head back to Syria, despite the unsafe and critical situation there–the situation that forced them to leave in the first place, because, he says “at least in Syria, I know how to survive, I know how things are supposed to go.”

But Yasser’s family who resided abroad did not want them to risk their life again. His uncle, who lived with them in Cairo, offered to talk to his Japanese wife about processing their papers and taking them to Japan. His uncle had already planned on moving his own family to Japan and found that it was opportune time for Yasser’s family to come first so they are acquainted with how the refugee recognition process works in Japan, before inviting his own family.

This, yet again, changed the course of Yasser’s life. He and his mom had already decided that they preferred going back to Syria and staying there even during the war than staying in Egypt, but he says “God had different plans for us to come to Japan.”

1.4. “God had different plans for us to come to Japan.”

But a refugee’s life is full of whys and uncertainties. Having decided to head East, Yasser, and his family spent 1 to 2 months finishing their papers, only to have the Japanese Embassy in Egypt refuse to take their documents without any explanation. When one is forced to flee, no amount of preparation guarantees a smooth-sailing trip to a new life. Like many refugees, Yasser and his family put in effort to provide the necessary requirements to facilitate the procedure of moving to Japan. However, there is arguably only so much one can do when the system itself seems to be at odds with you. “We had everything, legal documents, we even had a residency in Egypt–we applied for the residence just for that. We put ‘family visit’ [on the documents] and submitted my uncle’s wife’s salary, taxes, slips–she sent all her documents,” Yasser recalls. But despite their preparations, Yasser recounts that the Embassy rejected their papers and said, “You have to go to either Jordan or Lebanon.”

2. Layover in Lebanon

Yasser remembers the 17 days he spent in Lebanon fondly. They entered with a visa for their appointment with the Japanese embassy; coming to the country with a defined goal–to apply for the Japanese visa after being rejected in Egypt–Yasser and his family knew that their time in the country would be limited, and in a way, their last hurrah.

“The two weeks in Lebanon, they were really, really, really good.”

Another reason why Yasser remembers their time in Lebanon with such delight is that it was one of the last moments of ease together as a complete family, with his dad finishing his job contract in Qatar and coming to Lebanon to be reunited with the rest of the family, “I was with all of my family because my dad at the same time came back from Qatar, he stayed with us for like a week. He came after us to Lebanon and then he went back to Syria and we came to Japan. We were all like family together also. It was really fun. I was just around the area hanging out and stuff with my family,” he recalls.

While they were not in touch with other Syrians in Lebanon, Yasser also remembers being warmly received by the Lebanese. He also recalls going to cafes, restaurants, and the seaside, talking to random people, and having fun.

But with his dad out of a stable job, their family’s conversation around money changed. From their comfortable housing situation in Egypt and their ‘fun’ experiences in Lebanon, they now had to think deeper about the cost of living, as their stable monthly flow of money from their income became limited savings.

From his life back in Syria to Egypt, to the two weeks spent in Lebanon, it is evident that Yasser grew up with the opportunity to experience finer things, even at the beginning of their refugee journey. Many portray refugees as people who struggle all throughout their process of seeking asylum–that the road to being recognized as a refugee is a linear, patterned, process. This portrayal often ignores the denial that comes with a drastic life change–the denial that Yasser found himself in Lebanon. He had lived a great life and was doing well, why did that have to change? Why did they have to change their lifestyle just because they had to relocate?

But as time passed, there was no room to deny and ignore the realities in front of them. Yasser was forced to accept his circumstances. With no means of sustaining themselves apart from their savings, their lifestyle inevitably had to change. The last bit of ‘fun’ that Yasser experienced was in Lebanon as his life took a turn as he embarked on his journey in Japan.

3. Journey in Japan

3.1. “The first six months in Japan was the worst period in my life.”

3.2. “When we came to Japan, we had zero, we had nothing.”

3.3. “The first seven months we felt like, ‘OK, get out of here’.”

Six months after they arrived in October, in April 2014, Yasser finally received his work permit. He took on various menial work to get by, as will be outlined in the next section. To provide for his family, Yasser had to momentarily forget about his personal goals. He was a university student at the premier university in Syria when he left; he decided to leave Egypt despite the comfortable living situation because he was unable to proceed with education or work.

Now, he is yet again forced by his circumstances to adjust, to accept this drastic lifestyle change. At the time, Yasser was thrown into accepting a new responsibility as the breadwinner of his family, not only of his mom and sister who were with him in Japan but also of his dad who had then returned to Syria and was without a job. He had to prioritize providing for his family, even if that meant postponing his personal goals.

Not only did he have to take financial responsibility for his family, but he also had to become their rock as they went through the interview procedures for the refugee recognition process. Yasser recalls that the interview was like an “investigation”, “you will have some employee from the immigration sitting at the table with a translator and, or an interpreter, and then they start asking details, you know, mostly about your situation in Syria,” he said, adding that “they target for a political situation more because you need to prove that if you go back to Syria, you’re in danger or, you know, you got to prove your dangerous situation. This is really hard to do. It’s not easy. And for me at the time, because I wasn’t in that great mentality at the time, so I just was giving them short answers. So I did my interview in one day and I was over.” In the midst of all the patience he had to demonstrate to adapt to their lifestyle change, Yasser admitted his impatience during the interviews. He felt as though there were “better” things to spend his time on than answering detailed questions to prove the validity of a situation he was already deep in the midst of. He felt like it was better to work, to find ways to secure a good future for his family, as opposed to revisiting scenarios of his life that he was forced out of.

3.4. “You need to prove that if you go back to Syria, you’re in danger.”

At that point, returning to Syria was virtually impossible–if Yasser and his family were to go back to Syria, they would be in danger. However, it took a long time to prove this fact to the Japanese government. While Yasser only had one 7-hour interview of the officials asking him about “everything, even silly details like what were you eating there, questions that don’t make sense”, his mom, who worked in Syrian National TV for 20 years had to undergo the mental toil of seven day-long interviews.

Yasser remembers seeing his mom cry after every single interview, drained as she was forced to recall fresh, painful, and detailed information. This presents another reality that seems to often be overlooked when it comes to refugees: that they do not actually live through the circumstances that forced them to flee just once. They are forced to relive difficult moments of their life–to revisit experiences that no one deserves to live through even once, multiple times, just to prove themselves as they start anew. It is an interesting reality that presents a question in the humaneness of a procedure that is supposedly intended to extend humanity.

3.5. “After seven interviews, she gave a lot of information, and I think because of her, we got the status.”

Yasser is fully cognizant of the fact that his mom’s interviews and her work background in Syria enormously helped their case. “My mom’s situation and the information she gave them, she could prove with papers, companies, documents, everything. She had stories also that put her in danger with her work being known as opposing the government while she was working for the government. She proved a lot of these she mentioned, she proved she would be in danger.”

Finally, after one year and a half of toiling interviews and hard work, in March 2015, Yasser, his mom, and his sister were recognized as refugees in Japan, along with 24 other people recognized in 2015 among 7,586 applicants.

4. Refugee Recognition

The life of a refugee, while filled with many uncertainties, aims for one certainty among anything else: the certainty of being recognized as an official refugee in the asylum country. Being recognized as a refugee, while not an ultimate guarantee to a better life, means that the refugee can now adapt to their new life with fewer limitations. To Yasser, being recognized as a refugee in Japan meant that he could now continue the life he had to postpone when he initially came–he no longer had to suffer through the day-to-day uncertainty that came with not knowing whether or not he would have health insurance, whether he could work, whether he could study. With his living status being certain, for the first time ever since fleeing Syria, Yasser was now granted the privilege to freely live. Past the danger of staying in Syria and the unsustainability of staying in Egypt, in Japan, Yasser was given a brand new chance.

With this new chance at a new life, Yasser had to learn and redo things. On September 2015, he began a Japanese language course with the Refugee Assistance Headquarters (RHQ) under their Settlement Support Program. A year later, he decided to apply to get a scholarship to Meiji University.

When he got into Meiji University and started in April 2017, however, Yasser was not the same Yasser who studied English Literature at Damascus University three years prior. Not only did he change his major and decide to focus on Globalization, Financial Services, Business Administration, and Economics instead of English Literature, his main goal in university was reformed into wanting to build his future–to find certainty for what’s to come because he now had full control of his present.

4.1. “University for me was like, it’s giving me time just to sit back and build my future.”

But forging connections and building his future did not mean that Yasser gave up on the prospect of having fun. At university, while building his professional network and going on research trips, Yasser was simultaneously meeting people from all over the world. He got close to many fellow students with diverse backgrounds, partly because of his role as an orientation leader, “Because I’m very outgoing and I don’t get nervous in front of people doing speeches, I was the one who was doing the orientation for the exchange students who came every semester, to give them advice, what to do and everything. I had the chance to always meet new people, to get to know everyone from the first day. I got to know even more people compared to other students,” he recounts.

Although Yasser knows that many refugees tend to not disclose their status because they feel that it comes with a negative connotation and “they want to be on the safe side” so they merely say that “I’m just a foreigner in Japan without mentioning their history or how they came,” the people that he got to know at Meiji knew of his refugee background, “I’ve never been ashamed of saying that I’m a refugee. I was like I’m a refugee, I can be that and that.”

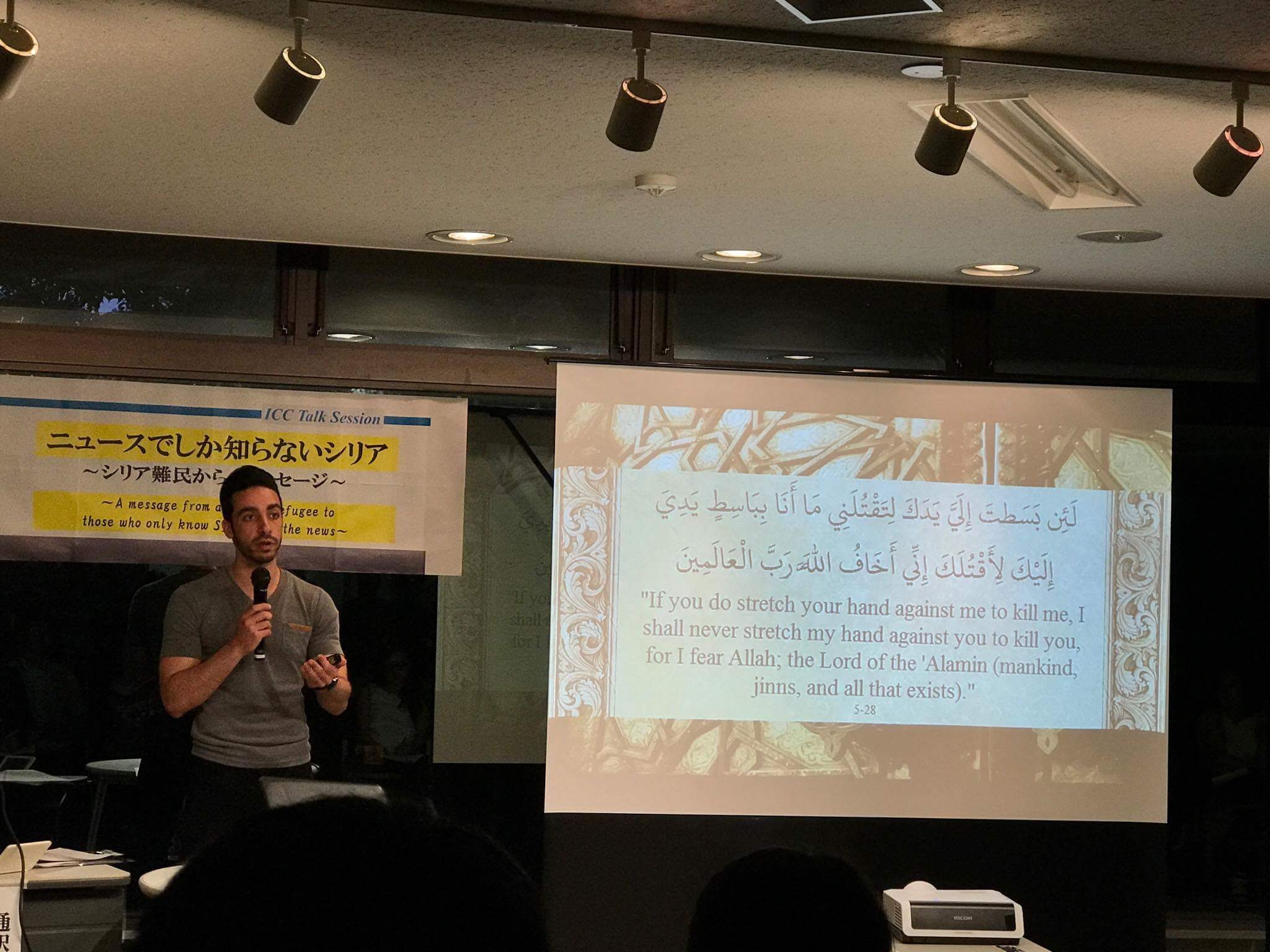

But many of his friends and other Japanese people at his university were unaware of Syria and the refugee situation. “I met some students who didn’t know where Syria is. A lot of young students at the time, especially with Japanese students was like Syria, you know, like, you know, どこ?中東ですね。トルコの下ですね。[Where? Oh in the Middle East. It’s below Turkey.] and then after I keep in contact with these people, they start asking me questions and I, like a lot of them, got interested and started doing a project for their classes or their homework. I was happy actually that I made a lot of people curious about, like where I’m from or like my religion or about refugees. So I was really happy and always welcome to talk to anyone.”

This lack of awareness about the reality of the refugee situation and of countries, like Syria, which are in the midst of conflict and therefore produce many refugees, is part of the reason why the refugee acceptance rate in Japan is low–because not enough people impose pressure on the government to take in more people seeking asylum. In 2020, Japan accepted a mere 1.2% of its refugee applicants. Having successfully gone through the refugee recognition procedure himself, Yasser thinks that this is largely because the government seems to not want people here.

“When I was first in my situation, it feels really annoying or you feel the aggression, it’s like–I can work, I can do stuff, you know, why they don’t accept me like I’m young and I have the energy and I want to do stuff. I want to learn the language, but they don’t give me the chance.”

Often, refugees in Japan are not given the time of day because they are lumped among a small group of “fake refugees”– people who come to Japan under the guise of a refugee, even though they are only actually in the country as an economic migrant. Many tend to justify the low refugee acceptance in the country with the existence of these people. While they do unfortunately exist, it would not be a stretch to say that a majority of the people who apply for refugee status in Japan are people who were actually left with no choice but to flee–and Yasser aims to shed light on this reality.

Aiming to use his position as a recognized refugee, with his experiences with uncertainty in Egypt and Lebanon and the hardships he had to endure in Japan, Yasser wants to emphasize that refugees like him, are doing their best to make their mark in their new country of residence. They are not to be ostracized and stigmatized–they are doing their best to survive, adjust, and adapt to the unusual circumstances they are forced into as they begin a new life.

“I’m a refugee and I’m doing great. I’m doing my best. And I’m like anyone who lives in this country.”