In February 2013, Yasser’s house in Syria was bombed. Although he had already planned to leave Syria after he graduates from university, he decided to hasten that plan that day and left his home with his mother and his sister soon after. On this page, Yasser narrates his stories from the years he spent in Syria until that day in 2013, giving us a glimpse of his experiences of growing up under the reign of the father-and-son Syrian presidents, Hafez al-Assad (in office: 1971-2000) and Bashar al-Assad (in office: 2000-today, as of August 2021) − the experience of growing up in fear, hostility, and oppression.

“I grew up fearing them, you know…al-Assads, even to just whisper.”

1. Who are the Assads?

1.1. Basics: Assads and Alawites

Although Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a non-monarchical state, the Assad family of the Alawite background has ruled the country for 50 years, effectively making the government under an authoritarian hereditary dictatorship. Throughout the half-century of their reign until today, they have been often criticized for various human rights abuse while they have remained powerful figures since Hafez al-Assad came into power in 1970.

his son Bashar al-Assad (right) (BBC)

As Yasser introduces, the Assad family comes from the Alawite background, named after the mountain the community is from, and therefore other Alawi people have a strong connection with the family as they are essentially related. Hafez al-Assad spent years building networks in his post as the Commander of the Syrian air force and Minister of Defense and succeeded in taking over the power in 1970 with a coup d’état. Through the following years, Hafez proceeded to cunningly create a system of divide and rule that gave him the power to rule the state alone.

1.2. Alawi Privilege

“The Alawites are getting all the advantages that normal people can’t take part in.”

Because of the said connection with the Assad family, Yasser shares that the Assads have treated Alawites specially and distributed opportunities unequally to other populations. At school, having Alawi kids was a sensitive matter for teachers as behind them are powerful figures in relation to the regime; as a result, teachers may turn a blind eye to the actions done by Alawi students. Outside school, being Alawi and having a connection with Assad is almost essential in order to be promoted. “Life is much easier in Syria if you know someone who is powerful in the country”, Yasser says. The unfair treatment and unequal distribution of opportunities between the Alawites and other citizens have caused dissatisfaction and hostility, which he grew up listening to people complain about. Nevertheless, he states that it never became an issue when making friends − that is, until the war started and people began to take sides. “You wouldn’t ask your friend if they were Alawite or Christian, it didn’t matter to us. We were always one, there was no difference. If it wasn’t for the war, I think it would have been the same,” he reflects.

2. School Days of Fear and Hostility

2.1. Brainwashing School

Generally speaking, young children associate the first day of elementary school with a scary but exciting time getting to know their teachers and making friends. For Yasser, it was wearing a uniform with the logo of the Assad party, symbolizing that they belong to Assad. The logo was printed on the chest part of the blue dress, the back of the orange scarf, and even on the small hat. On top of the symbolic uniform, Yasser also shares that the teachers at public schools were authoritative, at times abusive, figures that students were afraid of. What was supposed to be an established place of learning felt like military service, or even worse, “prison” for Yasser.

(The Guardian)

The oppression he faced at school was not limited to the uniform. He recalls seeing pictures of the Assads everywhere at school, even on the playground, and greeting them in those pictures every morning. He casts doubt when asked if the children were aware of the political meaning it carried. He suggests the habituation of support for Assad, saying “They do whatever the system repeatedly teaches them to do”. The forced reinforcement of the political support was “brainwashing,” Yasser adds. Little children continue to go to school in the political uniform, saluting to Assad in the morning and studying at the facility full of portraits of the Assads to this day.

“Even during high school, if I wanted to mention Assad’s name, I would whisper.”

The fear of Assad at school also grew at home for Yasser. He shares an incident with his relative that made him become more careful of what he said about the regime, “He was arrested because he was against Assad, and we never heard about him again. They just arrest them and you don’t know what happens after that. My mom knows people who really disappeared, just disappeared”. With this story he heard from his mother at home and the repeated extreme display of support for Assad back at school, Yasser slowly grew to fear even mentioning Assad’s name. In the classroom mixed with students from a background close to the regime, he would ensure using the appropriate title, adding “His Highness”, and whispering when he would talk about the family, even on a positive note. He eventually came to feel anger for having to treat the president as if he was God. Growing up, a large portion of his school days was tainted by oppression.

2-2. Giving Up Soccer Career

“I saw it as a goal to pursue but in Syria, it’s not really possible.”

The oppression he faced growing up was not the only case at school; it had reached his passion − soccer. Starting as a junior high school student, he worked his way up from Division 3 to Division 2, and eventually Division 1 as a university student. He began to see a career in soccer as a goal to pursue and invest more time in training, showing up to practices earlier than anybody else on the team. However, Yasser shares a shocking comment made one day by his coach who had seen how hard Yasser was working; “he told me, ‘Don’t take soccer as your own thing here because it won’t feed you bread’, he said exactly”. The advice took Yasser wholly by surprise, but he says he knew the coach was not talking about his skill as a soccer player. Just as promotion for his mother was difficult at the Alawi-dominant workplace, his chance of getting into the Syrian national team, run by the regime, was extremely low without having a connection with military personnel. Becoming successful in any field was much harder in Syria, especially in soccer where Yasser describes politics is involved “too much”. The discontent over the injustice had slowly piled up and expanded to form hostility among the Syrian people.

3. Living Through Revolution to War

3.1. Accumulated Hostility

Growing up under Assad’s regime meant that politics always got in the way of his life. At school, he was forced to show support for Assad by cheering for him and wearing a uniform with a logo that shows he belongs to the Assad party from a young age. Outside school, he had to give up a career in soccer as he does not have a connection with the regime. While growing a sense of fear at the same time, the years of his oppressed childhood surely had borne resentment against the tyrant inside Yasser. In similar situations, other Syrian people had shared the suppressed anger toward the circumstance, politics, and the Assads for decades throughout the regime. In particular, Yasser shares that there were two incidents that fueled the hostility of the Syrian people toward the Assad family: the Hama Massacre in 1982 and the death of Hafez al-Assad in 2000.

“Most Syrians hate al-Assad inside for what he did in Hama in 1982 – he killed 50,000 people.”

When Yasser was asked when he first became aware of the way the world goes around in Syria – the life of oppression under Assad’s reign, he answers it was mostly from listening as a child to what his family was talking about and trying to understand the situation. The atrocious 1982 Hama Massacre was one of those stories that he grew up listening to them talking in rage, contributing to his fear of the ruler. The Hama Massacre, described as one of the bloodiest chapters of modern Arab history, is the mass slaughter of the people in the city of Hama executed by then-president Hafez al-Assad in February 1982. Twelve years after Hafez al-Assad took over in Syria in a coup d’état, Hama had become the center of the anti-Assad movement carried out by the Muslim Brotherhood, a transnational organization advocating a healthy, modern Islamic society that had been active in Syria for six years prior. The action the president took to suppress the uprising and the attacks against the government buildings and military officers was the massacre lasting 26 days, and the aftermath was devastating − tens of thousands of people including civilians were killed and the city was left in shambles. The rising of Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood was effectively ended, and the regime of the merciless Assad was continued. Yasser says, “From there, people hate the family already, and I grew up fearing them”.

“When Hafez al-Assad died, markets were shut down and we had to weep as if God died.”

Yasser then talks about the time Hafez al-Assad died as another incident that “also made Syrians really hate the whole family.” In June 2000, Assad died of a heart attack in Damascus, aged 69. The news was delivered to the public by the announcer with a choking voice and tears in his eyes stating it was a day of sorrow and pain in every house, school, factory, and farm on the state-run television. The Syrian Government declared the next forty days to be the official mourning period, in which the nation’s flag should be flown at half-mast to honor the late president across the country. A crowd began to gather on the streets weeping for Assad and the city was shut down in the name of mourning. Shops were closed and any shops that remained open would be destroyed. Even though Yasser was still eight years old at the time, he still recalls the event to this day: “I remember watching people crying on TV and I used to hear stories from my parents, that people were forced to do so.”The result of Hafez al-Assad’s death, however, was not limited to the compelled mourning. Shortly after the news broke out, the Syrian parliament lowered the presidential age requirement by amending the Constitution in order to allow then-34-year-old Hafez’s son Bashar, who was to succeed his father after the death of his elder brother Bassel in 1994, to be the next president. A nationwide referendum was held and Bashar, as the only candidate of the election and the representative of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party previously led by his late father Hafez, sealed the elevation and officially took over the presidency of Syria. Yasser reflects, “You can imagine what’s behind that”, hinting at the corrupted republic government under the regime. Through these incidents on top of the oppression people of Syria faced in their daily life, the hostility toward the Assads had surely and steadily accumulated.

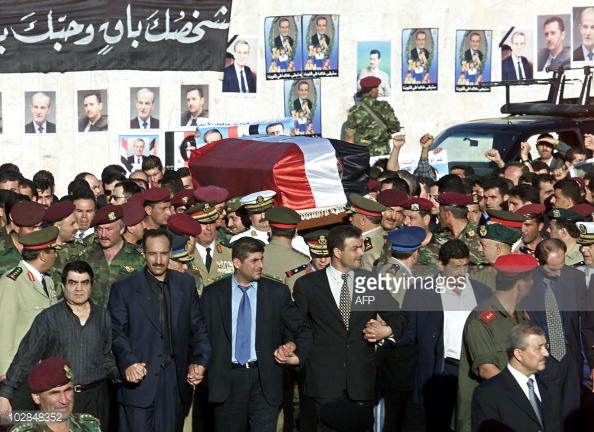

Right: The funeral of Hafez al-Assad (TeachMideast)

3.2. Arab Spring

“When the Arab Spring started, people thought, ‘This is the right time’.”

Another decade of longing for a change has passed and the piled-up hostility toward the regime had become much closer to reaching the boiling point. Then, Yasser along with the Syrian people saw what could be a bright hope: Arab Spring. In December 2010, a movement that will later be called Jasmine Revolution occurred in Tunisia, the Arab country across the Mediterranean Sea from Syria. What started as a protest against police by a street vendor led to a series of demonstrations in the capital Tunis calling for a change in the regime of the authoritarian then-president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, which had lasted for more than two decades, and succeeding in ousting him in January of the following year. Further motivated by the success of Tunisia, the pro-democracy uprising was soon followed by the neighboring Muslim states such as Morocco, Libya, and Egypt which also have been under instability and oppression. Syria was not an exception. Yasser recalls the Syrian people came up with a plan to follow the movement that had come to be called the Arab Spring. The plan was simple: make their voices heard, take down Assad, and elect someone new. They grabbed the chance to let out the hostility that they had bottled up all these years – a revolution was to begin.

3.3. Breaking the Chains

“You feel like you’ve been in chains for all these years and now you can shout against it.”

The execution of the plan began in late January. Online platforms were utilized to recruit activists and call for a “Syrian revolution”, but it would only result in allegedly small demonstrations in the northeast region at first. Then, adolescents in the southern city of Daraa got arrested, beaten, and interrogated for the anti-government graffiti they painted on the walls of their school. This incident prompted larger demonstrations calling for their release and rebelling against this treatment of the young students by the police. The wave of protests was gradually spreading across the country, extending its focus to the opposition against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. On March 15th, the demonstrations that had been held on a smaller scale erupted in Daraa, the northern city of Aleppo, and the capital Damascus. This is the day that is considered as the beginning of the uprising and what later became known as the Syrian Civil War which is ongoing to this day (as of August 2021).

Right: Demonstrators marching in Qamishli on April 1, 2011 (CNN)

Shortly after, the peaceful demonstrations pushing for democracy began to be suppressed by a violent and brutal crackdown by the regime, shooting and killing the protestors on the spot. The use of fatal weapons soon received international criticism; the national security council spokesman of the United States called to allow the peaceful demonstrations and the United Nations Secretary-General condemned the use of force as “unacceptable”.

On a Friday within the same month, after the main prayer, Yasser, still in high school at the time, joined the demonstration with his friends to show the hostility that Yasser had been accumulating through all these years. It should be repeated that by this point, Assad had begun to ruthlessly subdued the demonstration by violent force.

“If they saw you, you’re either killed or arrested.”

Yasser recalls the day, “It’s crazy, you’re risking your life there and people were being killed”. Despite the life-threatening risk, he reflects he was not fearing anything and felt his adrenaline rushing; for him, whose childhood came with oppression, seeing hundreds of people demonstrating that day was seeing the chance to finally break free from the chains he had been locked in and shouting the hostility that he had built up.

on May 3, 2011 (TIME)

Nevertheless, being there that day was a life-or-death moment. To the question asking if security officers were also at the protest with 300 to 400 participants, he plainly answers, “No, if they saw you, you’re either killed or arrested”, reminding that the “demonstration” in Syria had become far different from what you see on TV for other countries. It was far more brutal − Yasser reflects on another scene from the day; after getting attacked by the teargas of the troop, he saw a soldier grabbing his friend by the shoulder, then he heard someone shout and the next thing, his friend was shot and killed. Being there signified breaking free for the hundreds of Syrians who showed up. What it also meant, however, was a place mixed with anger and sadness where they risk getting arrested or even losing their life in order to voice their view peacefully. Yasser never returned to the demonstration as his mother strongly opposed it. He says he thought, “I’m never gonna do that again”.

3.4. Corrupt Media

People were standing up against Assad at last. However, the Syrian national TV turned its back on peaceful Syrian civilians longing for and calling for democratic reform. This was not something new − Yasser points out the lack of media coverage was a major factor in hindering people from taking action in both incidents that contributed to people’s hostility against the Assads: the Hama massacre in 1982 and the death of Hafez al-Assad in 2000. From what Yasser heard from his mother who had worked at the station, he reveals that this is due to the corrupt relationship between the regime and the mainstream media platform, where 70 percent of the workers are Alawites who hold a strong connection with the Assads as further mentioned above.

Because of this connection with the regime, the coverage of the uprising that had taken place was in support of Assad; the demonstrators killed were reported as terrorists and “brainwashing” propaganda, which did end up pushing some of his cousins to support the regime, was aired on the TV, Yasser says. His mother working in the media needed to pretend to support Assad, but what his mother witnessed became highly beneficial later during their refugee application in Japan.

3.5. Checkpoint of Life or Death

In July 2011, four months after Assad began to violently suppress the peaceful protestors, the Syrians were well-fed up with the oppression and began to fight back, some forming armed groups of their own. Although most of them were operative on a local and small scale, a number of groups grew to be extensive forces that affiliate across the country. One of them was formed in August and called themselves Free Syrian Army. The group was founded by the defected soldiers from Assad’s army with the purpose to be the military wing of the Syrian people’s opposition to the regime. With the formation of armed rebel groups such as the Free Syrian Army, what started as an uprising earlier in the year had become a civil war. When Yasser was asked if he considered joining the Free Syrian Army, he shares that although he gave it a lot of thought. However, he eventually decided not to due to the suspicion he developed about their leaders and the priority on his sense of responsibility for his mother and his sister. For him, his family came before politics under any circumstance.

A year later in 2012, the peaceful uprising had long turned into a full-scale, complex, and highly deadly war. Among a number of vicious incidents, the most deadly had occurred in February earlier that year; Bashar al-Assad massacred the city of Homs, causing the deaths of estimated 700 civilians, and blamed the opposition forces that had centered their activity in the city, just as his father did when he massacred the city of Hama thirty years earlier. According to a local resident, the sound of bombardment continued until 4 in the morning, leaving the survivors at a loss for how to bury so many bodies in the city almost completely destroyed. Although the region had suffered most from the violence by the regime, this horrific and ruthless shell was nothing like what had been done before.

“He was injured and closest to my place. So I took the car and went outside, risking my life.”

On the phone, Yasser learned his friend had been injured from the tank bombing at the checkpoint of the Free Syrian Army. He had just left the place to change his ammunition, saving his life but leaving an injury on his head from a fragment. He needed someone to pick him up at the mosque he ran in and called Yasser, who lived the closest to the place. Without a second thought, he went outside and took his car, risking his life. Yasser reflects on the scene, “The tank was there and when I crossed it, it bombed a building. Helicopters were in the air. It was a crazy day.”

“If they found out he was fighting against them, we were all dead. It feels like God’s work at the time.”

Yasser continues, “There’s nobody in the street, just war”. After a while, he found his friend and got him in the car. However, they saw an enormous threat on the way back home: a checkpoint of the Assad regime. Driving a member of the Free Syrian Army meant, the soldiers discovering his identity meant instant death. Thankfully, three things worked out to their advantage. First, his friend still had his ID − most Free Syrian Army members would break their ID with the stamp of the Assad party, the symbol of oppression − and they both could prove their identity. Second, the soldiers did not ask to raise the hat that was covering his friend’s injury, which otherwise would have been evidence of his involvement in the war. Third, the soldiers believed when Yasser pretend to be lost and asked for directions. They safely passed the checkpoint and got back home. Yasser reflects, “It was God’s work that they didn’t ask for more”.

Revisiting what happened on this day, Yasser further reveals that he did not feel fear during the tense, life-or-death event. Asked why, he suggests the possibility that he had gotten used to it, “Maybe I had gotten used to hearing the bombs and seeing people die. I was risking my life but I didn’t feel any point of fear. If Assad’s soldiers would kill us or not, I didn’t care about that. All I cared about was to save that guy, and if we didn’t make it, we didn’t make it together. I was just scared of my mom’s and my sister’s reaction”. Along with his comment on their survival being God’s work, his account of this day illustrates key characteristics of Yasser: faithful, holding Islamic beliefs at his core, and altruistic, always willing to care for and protect those around him, primarily his family.

4. “We’re Leaving, No Discussion”

4.1. Ongoing Brutality

“None of the Syrians thought it was going to be that brutal.”

By the end of the year 2012, the conflict had escalated into a complex, multidimensional proxy war among multiple parties with different allies and different priorities. It had come far away from civilians rebelling against the government, as it started in early 2011 under the influence of the Arab Spring. By then, the following groups had come into the picture and formed complex triangular relations: A) the rebels, including the Free Syrian Army, backed by the Persian Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and an al-Qaeda militia called Jabhat al-Nursa, B) the Assad’s regime, backed by the extremists purposely released from prison by Assad and the prominent ally Iran as well as Lebanese militia called Hezbollah backed by Iran, and C) the armed Syrian Kurdish. The Kurdish are a group of people of Iranian ethnic descent and they are estimated to account for 9 percent of the Syrian population. Their main faction the Democratic Union Party had established a foothold in the north region early in the war and they had informally seceded from Assad’s rule, claiming regional autonomy within a decentralized Syria. Amid the escalating conflict, the ruthless campaigns the Assad’s regime repeatedly launched on their unarmed civilians continued to cause countless deaths, with the number 2,336 confirmed in June − about 80 people per day on average − according to the statistics by the Syrian Network for Human Rights. Yasser reflects, “Assad would burn cities and the remains are still there. None of the Syrians thought it was going to be that brutal”. Nevertheless, in spite of the growing violence and brutality from the regime and the simple plan of democratic reform taking much longer than the fellow Arabic countries, Yasser says he kept his faith in the revolution. He knew that what he could do was to be patient and believe in the good that would eventually come out of this horror, as promised in the Koran.

4.2. Bomb on the Roof

“I still remember the scene of everyone going down the stairs crying and yelling. Then, the shell came into our roof.”