Being a refugee in a completely new environment puts them in a vulnerable situation where they have to endure whatever difficulties may come. As a working refugee, Ariana has undergone hardships, discrimination, and unfair treatment throughout her working experiences in a new environment. In this section, she narrates her story of grappling with such challenges as a working woman.

1. Working in Iran

1.1. Desire to be Independent

“The society I was there never could support me.”

Note: This narrator’s face is blurred at their request for privacy.

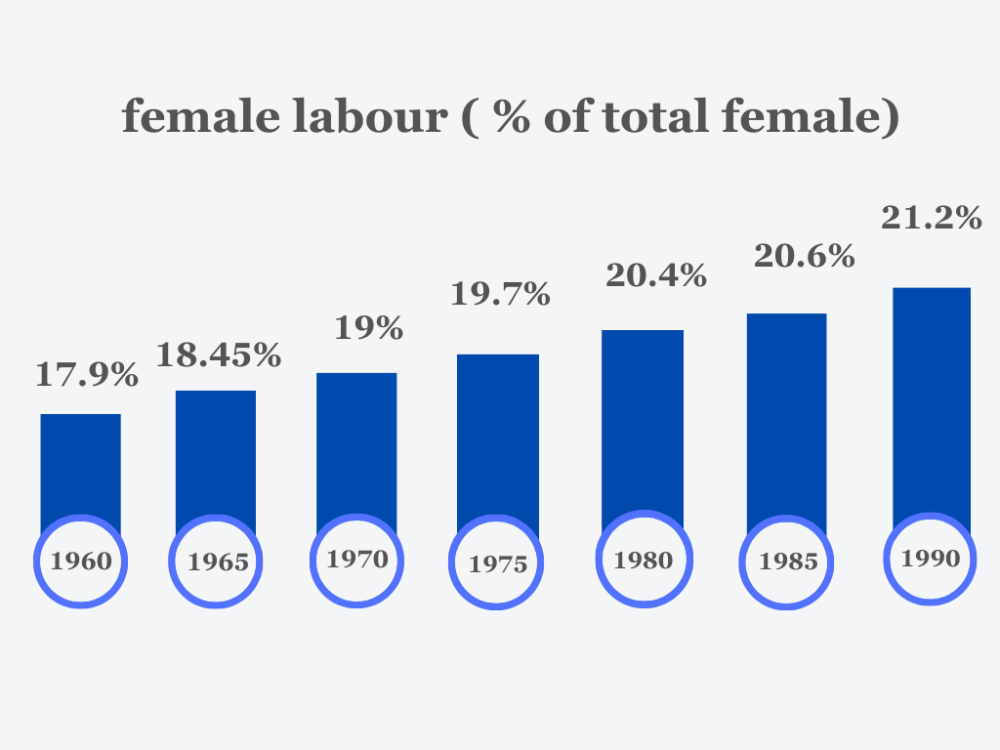

As a little girl born as an older sister of two brothers, her strong sense of responsibility started to grow at a young age. She showed a keen interest in having all the knowledge in the world, particularly in physics, chemistry, and astronomy. Being raised by a mother who worked as a teacher at an elementary school played a great role in providing her with the idea of what it is like to be a working woman in Iran. In the early 1990s, when Ariana just started working, the change in the participation rate of women in the workforce was prominent. This change has influenced her perception of the participation of working women and convinced her to join the labor force.

Starting to work from a young age is not common in Iran, especially for women. However, despite the social expectation of staying home as a young girl, young Ariana confronted her father and showed her urge to have a job and be independent, at the age of seventeen. Although “protesting” against her father seemed a bold action, her intention came from her strong sense of responsibility and duty to make money, so that she could support her family financially and take back the “good life” she had before the change of regime.

“I want to work because I want to be independent and I want to make myself stronger and I want to help.”

1.2. A Complete Change Under the Islamic Republic

“Yeah, this is Iran. Everything is the opposite.”

After Ariana successfully confronted her father, she soon started to work in two different positions at the library and computer center at Tarbiat Modares University so that she could get enough money to support and help her family. Working in a cozy environment, with some flowers on the table, at a prestigious university seemed like an ideal workplace, but it turned out the reality was different.

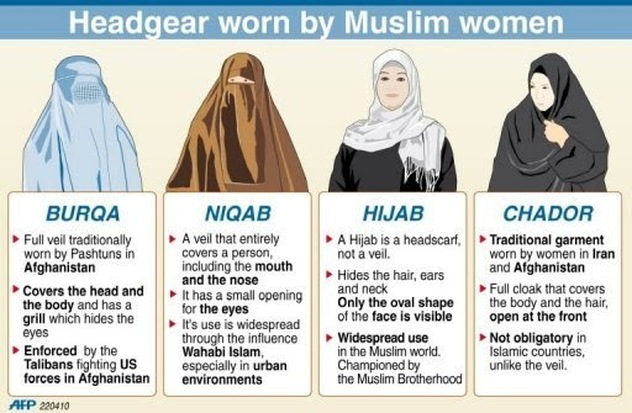

Ariana explains she was in a situation where she had to tell “lies” to her boss and pretend that she was religious. To abide by the religious law, she had to follow the strict dress codes and wear chadors, a full-body-length cloak that covers the hair and body more than a hijab does. She further explains that the capability of acquiring jobs or keeping the position is all dependent on how good these “lies” are, saying “the job position did not depend on the skills of people, it depends on the skills to say lies.” This made her question the working situation in Iran and gave her the impression that everything in Iran is the opposite of the “regular.”

“Religious people in Iran have more opportunities for making money,” Ariana says. Her first professional experience in Iran gave her a strong impression; the people who have strong connections with religious beliefs in Iran are more “thirsty” for money and sex. For example, her male boss at the computer center was holding off paying her salary by extending the payday, resulting in her having to rely on one source of income from the library to support her family. On top of the labor exploitation, she says she was getting sexual comments from her boss although her body was fully covered in a chador. She recalls the time as follows: “He started to talk about stories kind of sexual or parties with dance, and I remember [thinking] that ‘Why he say this kind of stories for me?’ I didn’t understand that time. But after I get a little bit older, I understand, Oh my God, he was a bad man that wanted to fool me as a girl.”

At that time, she was too young to comprehend the situation. However, she recognized the incident as “sexual harassment” later in her life. The only coping mechanism she could think of in that situation was to leave the workplace. For a 17-year-old girl, who just started working and was surrounded by older coworkers, without any work experience, the presence of a young female co-worker had a positive impact. Being in the same boat, Ariana says she gave up her position after finding out the only other young female colleague was desperately in need of a job. While she was happy with this act of altruism, she lost her only source of income and found herself in a precarious situation, financially and mentally. This had a huge impact on her beliefs and her views on religion, and she began to question Islamic ethics, which later on led to her motives to engage in political activism.

Soon after, she was able to find the next job at a construction company through the connection of the professors from the university who recognized Ariana’s kindness and amiable relationship with her fellows. A while after she started working at the company, she found out that her boss, who was newly married, was having an affair with a young schoolgirl. Although the guy was in a higher position than Ariana, she mustered up her courage to confront the guy. “I talked with him and told him. Excuse me, I cannot help you to cheat your wife and this young girl. I’m a girl, too,” she said. When he asked Ariana to take a phone call from the girl at the workplace, not only did she explicitly tell him that she did not want to be complicit in the situation, but she also helped the young girl understand that she was in an extramarital relationship by insinuating that he was married. However, what she thought was the right thing to do ended up costing her the job:” I was very young at that time, I thought it’s not correct, and I cannot help this process. And I think because of that, I finally lost that job too.”

2. “Modern Slavery” of Refugees

“Refugee is modern slavery, I think. They have to do the most difficult work with the lowest price.”

Ariana feels that being a refugee is like being a slave in the modern age because of so many conditions that limit their opportunities and push them to an exploitative working environment. For refugees who arrive in the host country with less locally applicable human capital such as language and job skills, they are more subject to start at significantly lower levels of wages and employability. Combined with legal restrictions that come into the picture for refugees and asylum seekers yet without a secure legal status, they are thus vulnerable to exploitation, which underpins practices commonly referred to as “modern slavery.” Through all the jobs that Ariana has had in Japan, we can understand the difficulties she has faced: legal restrictions, religious connections, exploitation, discrimination, and precarious work.

2.1. Limitations by Visa

“And many times because of my kind of visa, my visa status, I couldn’t have the job.”

When it comes to finding a job in Japan, there is one crucial condition that restricts refugees’ choice of work: visa status. Refugees in Japan usually have either a status of permanent residence, if they were legally recognized, or a specific type of visa, usually Designated Activity, a 6-month temporary visa given to those with pending refugee applications. These visa statuses specify how long they could reside, what kind of access they have to social welfare, and most importantly, what kind of jobs and activities they could engage in. The visa status would allow them to work, but at the same time restrict them from getting the opportunities that are available for them, including what kind of job they want. “I just know it’s six months, and also, I have permission for working, but not every working,” Ariana expresses her frustration.

2.2. Inescapble Chain of the Islamic Republic

As Ariana embarked on the journey of finding a new safety net to support herself and her family in Japan, she was mapping out the possible occupation she could find as an Iranian woman within her visa restrictions as soon as she landed in her new destination. The first idea that she had was to get a job related to Iranian carpets. Having knowledge of how lucrative the Iranian carpet industry is, she thought that she could make enough money to sustain her life in Japan by making Iranian carpet. She was also aware of the difficulties of finding a job for foreigners in Japan due to the language barrier. She was hoping, maybe, this would allow her to get a job more easily.

But in reality, Iranian people who work in Iranian carpet industries have strong ties with the Islamic government and the Iranian community in Japan. Due to her firm political standpoint, her initial intention and hope of working in the Iranian carpet industry did not come true. At this point, she encountered the difficulties and realities of finding an occupation in a new environment and realized the influence of the Islamic Republic was everywhere, even in Japan.

Ariana herself believes in a strong correlation between identity and occupation, and she also looks for occupations that could help society and people, and that match her identity the best. Back in Iran, she was helping people as a counselor in a non-government organization, and she recalled the experience as “the best activities she was part of.” Even now she considers that if money allows her, she is willing to work for people and not for money. Due to the necessity of sustaining her life in Japan, the only choice that is left for her is to get an occupation that keeps her alive.

2.3. Exploitation of Vulnerability

As her savings were coming to an end, she put her best foot forward to seek any forms of help she could get, from finding organizations to getting in touch with people from Iran. But even amid the process of seeking some support, her core principle coming from her strong sense of responsibility did not change: “I want to find a job to be independent.” Thus soon after Ariana got an offer of help from an Iranian guy, she showed her willingness to meet with him without a second thought. At first, he promised her access to a stable life by offering her a place to stay, a phone, and most importantly a job opportunity to work at a Kebab food truck.

Upon starting her work at a Kebab food truck, owned by an Iranian man, she moved from Hamamatsu to Gumma, as he told her. Initially, her role was making kebabs, but they continuously asked her to do more: cleaning their house, cooking meals for them, and walking a dog. On top of that, despite all the promises and labor he made her do, he refused to pay her salary due to the lack of zairyu card, or a residence card, and she was not able to confront him in fear of being accused of illegal employment.

All refugees face different degrees of hardships and difficulties in a new country, but for female refugees, there are always extra burdens and worrisome factors including sexual exploitation. In fact, many female refugees, like Ariana, tend to fall into a similar situation and are forced to agree to an unfavorable proposal to secure a way to a better life, yet these issues are not taken seriously enough considering the number of female refugees who underwent the transitional sex.

“I lost my job several times because I didn’t want to have a sexual relationship with the Iranian guys here.”

In Ariana’s case, he led her up the garden path with promises of support and steps to a stable life but never materialized. In addition to the Iranian man from the Kebab food truck, she was also invited to come to different places by people in the Iranian community for mutual support, but they kept cutting her on and off by giving her various reasons such as “You are not religious enough” or just by saying “It’s better for you to go.” But even though she was in such a situation, she never lost her initial purpose of supporting her family back home and had the courage to leave the situation. She kept reminding herself that she was just not here to survive.

2.4. Discriminatory Workplace

Being in a physically comfortable working place does not always mean it is a good working place for refugee people. For foreign nationals who come from a different culture, they have additional factors to worry about such as adaptation to the new culture, communicating in their new language, and maintaining harmony with their Japanese co-workers.

Working as a restaurant staff with a Japanese co-worker and communicating with them in her undeveloped Japanese was an uphill battle for her. In the restaurant, Ariana’s Japanese co-workers did not like to talk to her in English, even in situations when she could not understand any instruction from them, and they would get irritable with her. “Even they knew that I don’t understand Japanese, they preferred to speak in Japanese with me. And when I didn’t understand, their behavior was kind of angry with me. Or, yeah, for example, In this meaning, you don’t understand, or you are fool, or this kind of things,” she explains.

Working as a restaurant staff with a Japanese co-worker and communicating with them in her undeveloped Japanese was an uphill battle for her. In the restaurant, Ariana’s Japanese co-workers did not like to talk to her in English, even in situations when she could not understand any instruction from them, and they would get irritable with her. “Even they knew that I don’t understand Japanese, they preferred to speak in Japanese with me. And when I didn’t understand, their behavior was kind of angry with me. Or, yeah, for example, In this meaning, you don’t understand, or you are fool, or this kind of things,” she explains.

To ameliorate the situation, she tried various ways she could think of, from changing her behavior to trying to get to the workplace earlier than the other co-workers. “I tried to change myself to match the place, but I couldn’t be successful,” she continues. But after a while, no matter how hard she tried to be liked in the workplace, the attitudes towards her never changed. Even in such a tough situation, she says she was always trying to calm herself by singing: “Singing always can help me to be calm. So even in this situation in my workplace, singing could help me. Singing in a very, very low voice.”

This illustrates the discrimination that foreign workers often experience in Japan due to cultural and language barriers. In the total six months of working in the cozy atmosphere restaurant, Ariana had to constantly bear the pressure and unkindness from her Japanese boss and co-workers. Ariana remembers how nicely the Japanese co-workers were treated in a respectful manner by their boss and how differently Ariana and other foreign workers were treated. Employers that accept international workers therefore also need to make an effort to learn how to train or treat them and understand their different language proficiency to make an inclusive environment for everybody.

2.5. Demanding and Precarious Labor

“Kitanai, kiken, kitsui” – also known as “3K” in Japanese refers to the jobs which are “dirty, dangerous, difficult.” These are the kinds of jobs that have a negative stigma for putting workers in conditions of physical injury, exhaustion, or degradation. Ariana’s experience of working at two different meat factories was one of such 3K jobs, as she experienced all of the three conditions.

“This is the situation. This is the reality. I need to be strong or die. And my choice was being strong.”

The labor she was engaging in at the meat factory was more physically demanding. She sometimes had to push carts that weighed 500 to 700 kilograms, handle heavy pieces of meat, and be asked to work at a faster pace in a bitterly cold environment that she recalls feeling like “working in the refrigerator.” Although these conditions were the definition of the 3K jobs, Ariana was trying not to be bothered by the factors and tried to focus on the positive aspect of the workplace: diversity.

Unlike the former workplace, she could practice English with her co-workers with people from different countries such as France, Germany, New Zealand, and Nigeria, and experience a little bit of a sense of inclusion. Going from restaurant staff to a factory worker and engaging in a 3K job would be an example of what is referred to as “downward mobility” – the process of becoming poorer or moving into a poorer economic or social group – which is particularly often experienced by refugees due to institutional, structural, and socio-cultural constraints. Nonetheless, Ariana says she would rather stick to the factory role over a waiter at a restaurant.

“I could push a 500-kilo cart. But I couldn’t push the hateness.”

Just as Ariana found a workplace that she liked, yet another factor jeopardized her work: COVID-19. The pandemic was reported to have caused the loss of jobs for 100,425 people in Japan as of April 2021, and Ariana was unfortunately one of them. Despite having a six-month contract, she was let go on the grounds of not wearing a mask properly at the workplace. Being the first one among the other foreign workers to be laid off, she could not help but feel that she was the easiest one to let go, and she was reminded of her vulnerability as a single woman in a foreign country. “I said I need this job and this salary, and I will try to do my best. After a while, he, again, told me that sorry. I understand this is discrimination because of my gender and my nationality, and because maybe I’m the weaker person here, because I’m alone and, yeah. I lost my job easily and it was discrimination,” she reflects.

A loss of a job during a global pandemic is mentally degrading, especially when alone in an unfamiliar country. However, for Ariana, having a strong sense of responsibility as a mother with a mission to help and support her family back in Iran is what kept her going. She says that is why she was able to choose the right path, be strong, and rise from ashes over and over again. Though she could have avoided physically and mentally demanding 3K jobs by engaging in a different kind of occupation as a woman, she clearly states that was not an option for her: “Maybe some women prefer to work sexual works because it may be easier for them to, than working in a factory with heavy things and very hard physical things, but I really prefer to work in a factory, even it’s difficult.”

Fortunately, she was able to find another job as a security guard. As she made a fresh start with a strong motivation to support her family, she chose the night shift voluntarily so that it could give her some more liberation. Despite the cold weather during the wintertime, she stood outside and bore the frigid temperature at night for a long time. In addition, she also experienced discrimination from other foreign workers. She says they victimized her by telling her the false location of the crossing to guard and left her out. One night, when the boss mistakenly called for eight people instead of seven people, she was the first one who was asked to go home and was thrown out in the cold weather, at a time when her last train had already left the station. Jobs like these, where she believes she was subject to exploitation, discrimination, and precarity because of her gender, nationality, and legal status, are why she feels that to be a legally unrecognized refugee today is to be a modern slave.

3. Hope for the Next Generation

“I never knew myself I can pass this kind of situation.”

Ariana has been through many challenging situations. She fled from Iran alone to seek safety in Japan, where she continued to have the responsibility of supporting her family while she was barely able to support herself. As a female refugee, she has felt like a part of “modern slavery” with vulnerability to precarity at work and in life. She says things were so rough at times that even the thought of ending her life has crossed her mind. Nevertheless, she expresses she was able to keep moving toward the end of the tunnel for the next generation back in Iran, which gave her a strength that she was surprised to find in herself. “I told myself, okay, you are respecting people and you are protecting people and you earn money for that. And it’s a good thing,” she says proudly.

“I learned the things that made me to be a soldier. For my country’s future, for my next generation.”

With the responsibility and hope of making the future better for the next generation, her current dream is to open a vegetarian restaurant in Japan. She is sure that her experience of working at a restaurant and being an Iranian woman living in Japan with an international mindset and familiarity with global cuisine will help. She describes she aspires to cook Iranian, western, and Japanese fusion cuisine and entertain customers with her talent for singing. She wants her restaurant to look like a place that resembles Iran’s good old days, with a former Iranian flag, and filled with Iranian music and songs with her voice. She has another dream at the same time: attending university in Japan.

The aspiration of having all the knowledge in the world that she dreamed of when she was little still has not faded away. Although she is still tackling language barriers, she hopes to study at Sophia University. “I need to work hard to have enough money for making your dreams come true. You need to have money. You need to work hard to make money. So this is my dream, and I’m trying hard for that,” she describes. Her dream of attending university is just not for herself, but to achieve the dream of making the country a better place with her knowledge and responsibility, which was a dream she could not achieve when she was growing up in Iran. She hopes that this time, she and her future generation could make a better society together.