1. Surrounded by Love and War

1.1. An Iron Fist in a Velvet Glove

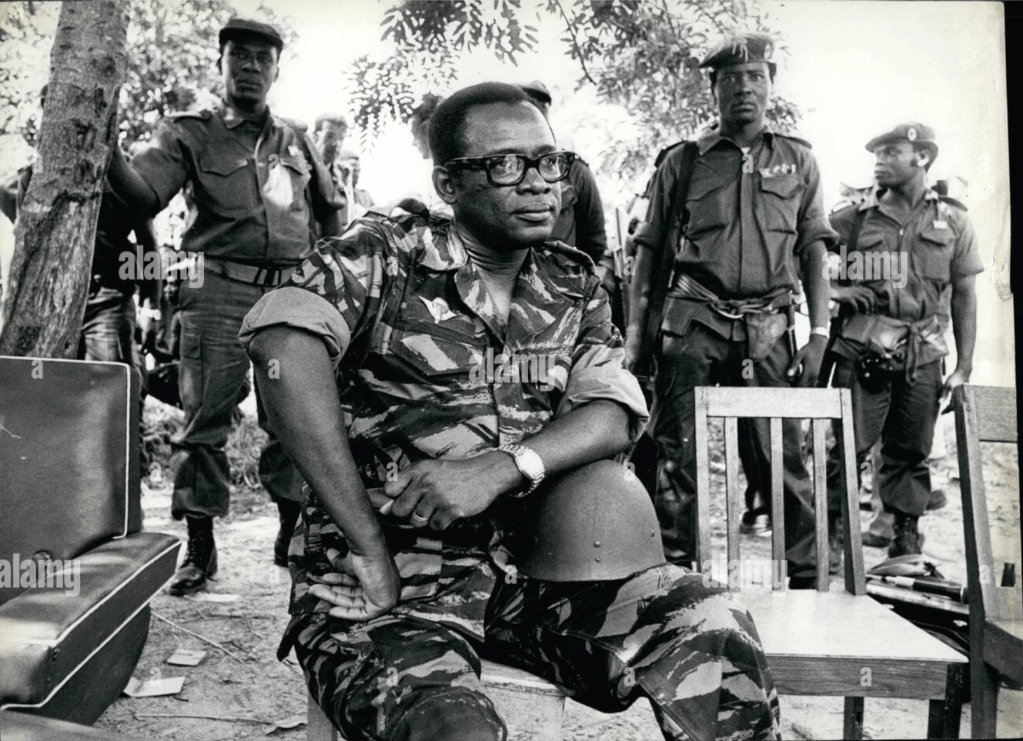

A smile in his eyes, Guillain starts to tell us about his family. He was born in 1987 when the actual Democratic Republic of the Congo was called the Republic of Zaire, a 16-year-old dictatorship led by the heavy hand of military officer Mobutu Sese Seko. The spring breeze of democracy and liberty that had a chance to blow on the independence of the Republic of the Congo from Belgium in 1960 soon went undermined by crippling corruption and civil unrest, provoking the coup in 1965, which led to a series of totalitarian measures. If these different regimes posed the same problems of insecurity and precarity for their population, Guillain, nonetheless, had the chance to grow up surrounded by familial warmth and strong expectations, being the eldest of his five siblings.

Right: Little Guillain carried by his father

Guillain strongly emphasizes the feeling of “too much pressure” because of his position in what he sees as a “typical family in Africa,” which, from a general standpoint, encompasses an enlarged notion of the family members and the implication of these members in one individual’s matters. We then can grasp the measure of having these expectations in the eyes of four boys and one girl, all looking up to Guillain’s irreproachable behavior. Yet, his siblings were light to handle compared to both Guillain’s mother and father, who with their strong guidance, pushed him toward discipline and effort.

A diplomatic position towards his father that Guillain had to adopt in order to “survive,” he said with a humorous accent, also describing his mom as “the same as an Asian mom.” Asian mothers are also called “tiger moms,” the expression conveys a sense of an exigent education and expectations given by a mom to her child, which was observed in the Asian diaspora in America, and which shows the belief “that success – in school, in work, and in life — is a meritocratic commodity; the more you put in, the more you get out.”

“At that time, I couldn’t like that I was feeling like it’s too much pressure, but now I actually… that was the right thing.”

Even with the pressure of his parents over his shoulders, Guillain’s lighthearted tone and humor betray his love for them and his gratitude for the effort-oriented upbringing they have given him. Along with moral and religious education, the main efforts of his parents revolved around school, as Guillain’s generation of siblings was the first one to attend university. His father’s scolds, which occurred “especially when [he brought] a bad result from school” were focused on preventing him from wasting his chance to thrive academically, representing investments in terms of funds for the family and decisive career opportunities, which proved to bear fruit as Guillain and his brothers achieved great results academically.

1.2. Not the Genre to Miss School

“My family had to push us, pushing our dreams.”

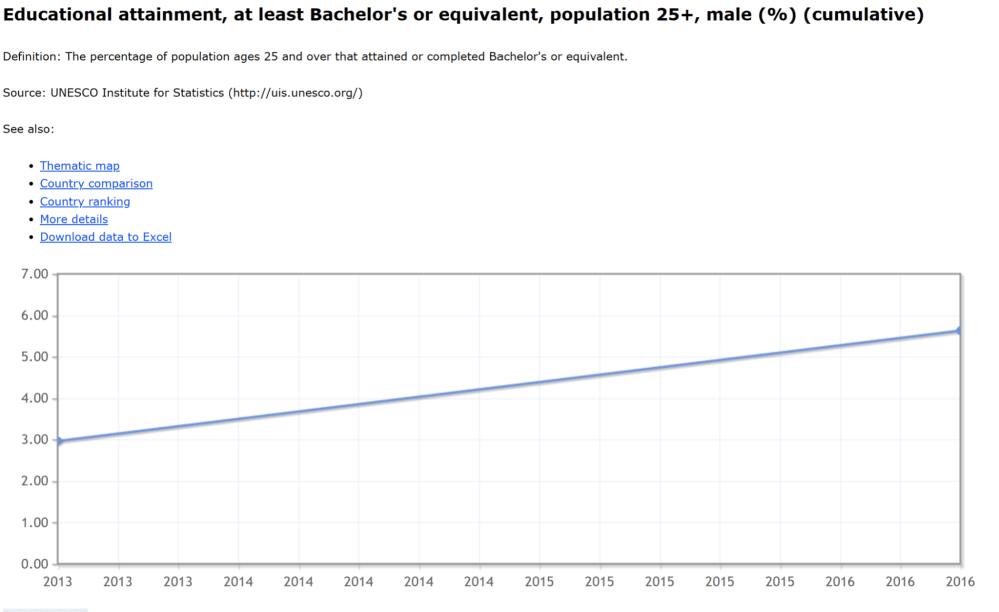

Despite being among the top five students at school, Guillain humbly praises some of his siblings for being “more focused on school than [him].” All his brothers achieved higher education, which in the context of DRC, especially during Guillain’s youth, was something only a tiny fraction of the population could achieve, even among men, who are given priority in education while women face other structural obstacles such as early marriage, teenage pregnancies, and expectations of girls’ roles in the household to name a few.

Indeed, what seems like a not uncommon academic background to us living in developed countries has to be taken into DRC’s education context: despite the increase in school attendance rate from the 2000s to today, the lack of infrastructure and school material, the absence of adequate formation for the professors and the conflicts and political troubles that directly affected Guillain and many others pupils keep the youth’s level of education to worrying lows. For example, 8.7 % of children aged 7 to 14 demonstrated basic reading skills in 2018.

“Not everybody in my area was going to school. So we was granted that grace to go to school.”

Another particularity of DRC we have to take into account to understand Guillain and his siblings’ education is the work market and career opportunities. In a country where 70% of the active population works in the agriculture sector, as opposed to generally below 3% in Western European countries, and the services industry is small, most of the urban and educated population is much expected to seek a job in an already developed field, such as law, economics, or medicine. Yet, Guillain tells us, he has a brother who is “the smartest” but chose to go into psychology.

Despite his brother’s choice not being dictated by his parents or by socio-economic expectations, Guillain’s family cannot be seen as “wealthy,” and he refuses to call them so. “We are not rich and my family and my father and mother, uh, all they can do [is] just support us,” he remembers with humility.

Even in a state ravaged by crippling poverty, Guillain could have an image of what extreme wealth could mean, as a handful of the wealthiest people, some of which are members of the diaspora going back to their country, could live in luxury villas located in private areas of big cities. One example is the Cité du Fleuve in the busy capital of Kinshasa, where Guillain worked after graduating from university. Guillain’s family, which he calls “a normal family,” seems situated between these two extremes. Moreover, its higher education also illustrates the pivotal position of DRC’s economic development. After suffering a negative annual economic growth rate of 8.42 percent between 1990 and 1995 under Mobutu Sese Seko’s dictatorship, the state’s economy started to rise again in the early 2000s and continues to grow at a steady pace. The country’s economic potential given the fair exploitation of its resources could skyrocket it into a leading emerging country, a dream which, Guillain knows, is obstructed by many educational and political challenges.

1.3. What Language Did Guillain Speak at this Time?

It was not until Guillain had both Japanese and English to learn in order to integrate into Japanese society that he started his language-learning journey. It was when he had to learn French, the official language of DRC, inherited from the Belgian colonization of its territory. Even after the independence and politics of “Africanisation” of the country, French remained a lingua franca and a means to access knowledge in a country inhabited by dozens of different ethnicities with each their own language. This situation also causes the population to be quite proficient in more than one local language, as Guillain recalls that “some people who come from westside and, they can’t speak Swahili so we can speak Lingala with them.”

“With my friends from university or some colleagues from work, so we have to speak French and then mix with Swahili. So, because we want to show that we are not, what can I say? We are educated people, so we have to mix.”

Most importantly, the colonial heritage of the French-speaking occupiers led DRC to the phenomenon of diglossia, the coexistence of languages of different varieties. While French remains the official language and is used in education, administration, and public domains in general, Swahili, also recognized as a national language along with other vernacular languages such as Kikongo, Lingala, and Tshiluba, is mainly used for conversation and in private instances. As Guillain tells us with this example, French is culturally and de facto a language of education and opportunities, pushing not only some families to favor it in their private lives but also in everyday social relationships.

Hence, Guillain’s ability to master French as if it were his mother tongue is not only an indicator of his performance at school but also a key to accessing a career in DRC, especially one in the health ministry. Given his struggle to adapt and study in Japan with a totally different set of languages from what he was used to, as well as the communication difficulties he had when given his interview for refugee status with a French interpreter, Guillain’s life has always been confronted to languages, and he hence does not ignore their political weight.

2. Be Stronger in a Longing for Hope

2.1. A Troublemaker?

As he confesses himself, Guillain had quite a turbulent character growing up; making jokes, “playing with [other’s] belongings,” and “[changing] names,” all of which contrast with his impressive academic standouts. Even if he gives all the praise to those of these “more focused” siblings, this temperament proved quite beneficial in creating Guillain’s lasting friendships, which also forged his active character.

“Just keep everybody active, something like that. I don’t want to see someone who can stay calm at school and then we have to joke with him.”

His ability to connect to different people, showing his social and adaptive side, finds its roots in a teasing, playful kid, still present in the doctor’s cheerful eyes. But it also helped him survive in Japan. If it was not for the bounds he made and the help he received there first, who can predict the fate of the man who achieved a master’s degree and worked in a country he struggled to adapt to in the first place?

But the doctor before us is calm and composed, as he recalls having to get through a lot of adaptive stress, not only in DRC but especially in Japan. Yet, the connections he made not only added to his personality even in his adult life, but this agitated environment he had to live in growing up, which he admits, can be a little extreme by today’s standards as he describes “now it’s illegal” with a grin, and it forged him for challenges to come.

2.2. The Law of the Joke

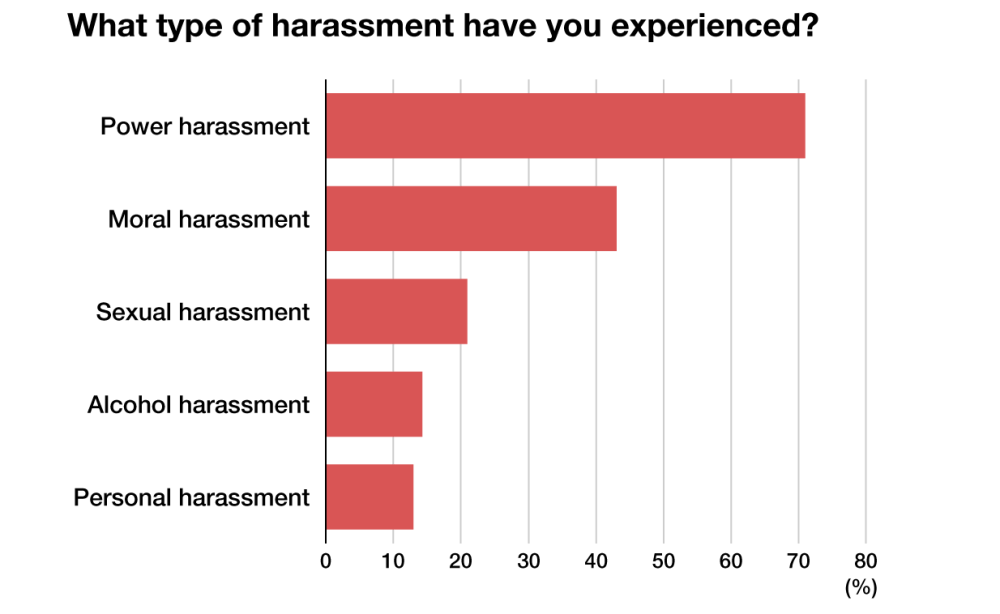

The streets of Kinshasa or Bukavu, where Guillain grew up since high school, are more subject to everyday violence, especially among gangs of “street children,” than the buzzy yet ordered avenue of Shinjuku-Dori. Nevertheless, as Guillain tells us, hierarchy and its abuses are still to be found between family and friends, and the strong ability to resist any kind of “joke” that he developed proved to be useful in a Japanese society in which still one-third of workers experience harassment in some form.

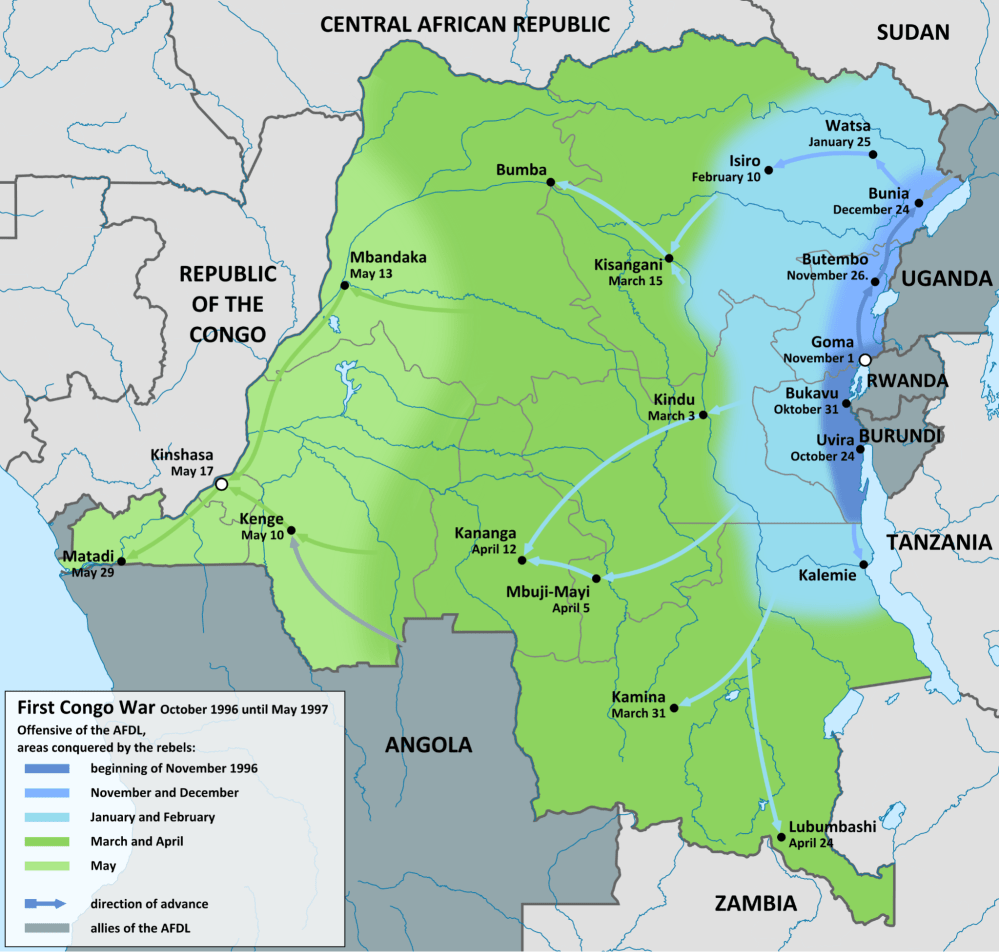

But behind the somewhat candid natures of these jokes lurks a darker reality. He was seven when the smoke of conflict came to his city. In one day unlike any other, troops of another ethnicity came from the nearby Rwandan border by the Kivu lake. Guillain and his family, fearing the ongoing massacres that had happened in the neighboring country, fled and hid in the bush for several months.

2.3. War Looming in the Horizon

“So the war in Congo is the worst in the world. More than, uh, 18 million people lost their lives.”

“Wracked by decades of conflict, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the most complex and long-standing humanitarian crisis in Africa and the fourth largest Internally Displaced Persons, another side of the refugee population, crisis in the world,” says a UNICEF report. It is a story about colonialism, lingering hate, and instrumentalization of conflict that, despite officially ending in 2003, still plants its claws on the country, affecting the population and Guillain, until today with military offensives of armed groups.

The Belgian and other European rulers of the Congo did more than kill more than half of the inhabitants of the country during the reign of Leopold II, they also institutionalized ethnic status and discrimination through labor separation and the issuance of an ethnic administrative document in Rwanda, their neighboring colony. The favored group for education was the Tutsi, they were pushed against the majority of the population, mainly composed of the Hutu and Twa people. Even if tensions between ethnicities and clans have been part of history under the vast Rwandan Empire, it never degenerated into the scale of the Tutsi genocide in 1994, when some Hutu, guided by decades of hatred and implicitly supported by former colonialists, started to commit mass massacres against the Tutsi.

Thousands of Tutsi refugees fled periodically into DRC even before this date, when they were called Banyamulenge. These were yet denied rights and excluded under Mobutu’s regime, leading to their alliance with the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), and their overthrow of Mobutu’s government in 1996. But the growing tensions with former Rwandan allies plunged the country into another war and a spiral of violence that the eastern part of the country (Bukavu and Goma are both situated in the Kivu region) is especially touched by. Yet, Guillain had to live amidst this everyday terror. Yet, Guillain had to face numerous interruptions of his youth, only to surrender to fear for months of negotiations between the two states.

“But no one care about that situation, because most of the international media try to hide that situation cause it’s not too good for business.”

Yet, a dreadful feeling of despair obstructed all the issues; neither the government nor international cooperation was able to prevent the attacks. As the mines in DRC are filled with cobalt, an indispensable material used for making electric batteries that profits to the multinationals and armed groups exploiting the miners, interest in the juicy mineral resources has led to the atrocities of the conflict being overseen by everyone in power to help.

The Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council addressed such differences as the following: “The war in Ukraine has demonstrated the immense gap between what is possible when the international community rallies behind a crisis, and the daily reality for millions of people suffering in silence that the world has chosen to ignore.” Not only did it take a humanitarian response plan for DRC to take over on year to be half-funded, but when it took one day for Ukraine, the media coverage of DRC was also around three times lower.

“That is why we need to fight and we need to talk about it.”

The West’s tendency to overlook Africa’s distress, which it has helped create, can be attributed to economic interests, cultural remoteness, or a biased perception of the situation. Despite the immense suffering of these people, the media often aims to sensationalize rather than address the seriousness of the issues. This is exemplified by the recent controversy involving French actor Omar Sy, who highlighted the problem with his poignant question: “Does that mean that when it’s in Africa you are less affected?”

“It is not only unjust – this bias also comes with a tremendous cost. Lives that could have been saved are lost. Conflicts are being allowed to become protracted crises and devastate the hopes of generations of people for a better future,” continues the Secretary-General. Still, Guillain cannot gaze away from all the threats he and his country have faced during this time. Furthermore, he cannot be discouraged by the suffering that maintains strength and resilience in himself. His family, his education, and his catholic faith have created a world where Guillain cannot give up hope. If a better future is not created yet, Guillain has to take a step to create it.

3. Carrying on His Faith

3.1. One of Many Christians

“Religion is important, religion made us what we are today.”

Guillain’s strong hope for change is rooted, as he tells us, in his faith. Having been raised in a catholic household, the doctor remembers how his and his siblings’ religious education played a role in their daily lives. Even if their turbulent behavior sometimes led to fights between them, it was “just for five minutes.” “Because we are Christians, so as Christians we know that, after every problem, so we have to solve it and go forward,” he describes. Something like “don’t talk to each other and take one week” apart had no chance to happen for them, as religion always made them believe that reconciliation was far more beneficial than everlasting resentment.

“And because, we learned value, good value from, religion. So for example, respect everybody and, don’t steal something that don’t belongs to you. So forgiveness and, love.”

Religious faith was intertwined with Guillain’s moral education. In DRC, where around 95,8 percent of the population is Christian as of 2005, religion and the Church playing an active role in people’s lives is indeed common. When he was a kid, Guillain went to church for mass every Sunday with his family, remembering that all services were “full of people” in a church that could gather around two thousand. More than a secularized institution, it was a bound for the community, as Guillain recalls that even “Muslim kids, they [could] join, we [could] go together to church.”

Catholicism had its first roots back in the late 15th century when Portuguese missionaries first made ties and eventually baptized the King of Kongo. In a land inhabited by other indigenous religions and systems of belief, syncretism grew between the local and the imported, rather than the Catholic Church simply erasing all unorthodoxy. As Guillain mentions it, the belief in witchcraft is thus still present nowadays, and, even more than causing some levels of resentment over a situation, it can lead to inhumane practices. More than the harsh reality of life alone, it is faith that made Guillain able to grow stronger and find hope in every moment. But faith was not given to his young self only through the Sunday mass. During all of his childhood and teenage years, up until high school, Guillain attended volunteer activities at church that made him take an active role in his community.

3.2. What Teaching of the Bible Impacted Guillain the Most?

When Guillain sought asylum in Japan, he was met with a lot of difficulties and closed doors. Yet, rather than discouragement, his combative attitude and inner convictions were not unsettled in the slightest. Bearing the words of God in mind, he kept going and going, reaching success after months of hardships. One of the most miraculous feats he achieved was certainly getting support money from the Japan Association for Refugees (JAR), after four interviews when he was systematically rejected, he finally got accepted on the fifth one. “I didn’t have another support so I couldn’t give up, to say that, even if they reject me, so I apply again. They reject me, I apply again,” he explains.

3.3. The Church Community

It was Sunday, early in the morning and people were already gathering before the church for the 8 AM mass. Guillain had to rise early, even earlier than the crowd now thronging at the door to enter. Because, today, he was waiting on the chancel, waiting for the people to surge into the church as the doors opened. Because, today, he was a choir singer.

“You are happy and all your friend, you have to tell all your friend. ‘That’s now I sing. Today all come to church.’”

The volunteer activities such as singing in the choir, preparing the mass, and sweeping not only reinforced Guillain’s bond with his friends but also with the community. As voluntary as they sound, these activities are in fact imposed on Christian households, as he tells us “We have to follow a timeline. So you have to join activity at church.” A means of support from the community that the church supports in return, managing large networks of hospitals, and clinics and having educated 60 percent of the nation’s primary school students. As Guillain grew up, he accessed more responsible positions, joining a group of students and later the “church committee.”

As the regime governed by Laurent Kabila started to incline more and more towards a life-lasting dictatorship, in 2016 when the actual president decided to report the new election sine die, the Catholic Church called for a national union against the regime. Guillain, now a grown-up who had more political knowledge than before, was already following the path of his faith and revolt.

3.4. From Church Activities to Church Activism

Following his activities in the church, Guillain started to get involved in other activities, notably hip-hop, which eventually led him to become vice-president of a major opposition party. Yet, the opposition became the main counterpower when the Catholic Church, considered the only national institution besides the state, called up arms for the organization of the elections of 2016. The Church in DRC not only has a habit of influencing politics, given the state of a regime where people could be “kidnapped” and tortured for disagreeing with the state, the untouchable Church and its churches were a real counterpower to the state and a safe space for a population in quest of freedom and new ideals. Hence, it was naturally in a church that Guillain started his activism by teaching the youth about the political situation. Moreover, Guillain found support in the Church when they were fighting together against the same enemy. Recently, the Pope of the Catholic Church planned his visit to DRC for February 2023, reaffirming once again the support of the Church in a context that still requires hope and strength for his population.

4. Keep Going: What Awaits Next?

Guillain, strong in his ties with his family, his rigorous education, and his unbreakable hope, was already engaged in the following of his story. A journey of hardships, pitfalls, and difficulties, but as the light only shines brighter surrounded by darkness, Guillain’s determination will ultimately bear a hundredfold fruit.

Achieving a medicine degree in DRC and pursuing his anti-regime campaigns, Guillain, despite working in the Health Ministry, was targeted by the government and ended up fleeing to Japan in 2018. But this crisis did not put a term to his determination. In 4 years in a new country, he learned everything, achieved a master’s degree, worked in a hospital in Kanagawa, and founded international projects to give aid and opportunities to DRC and do what “he could do for [his] country.”

Reflecting back on his youth, we see with new eyes how Guillain carries out his childhood environment, influences, and memories in his 35-year-old mind now. We see with new eyes how his profound experiences made him care for his country and his youth, filled like himself with a burden on their shoulder and the strength to carry it, feeling blessed by its weight as they kept going.

“So my message that I say, I, it is to the end, it is I have always been against politicians who tell us that the youth is the future. I say no and I say youth is the strength for the present because tomorrow will be too late and we will also leave the place to the new generation. So the change is now and we must also work hard to, for the next generation.”