Many people have heard about the coup d’état in Myanmar in 2021. 2,000 protestors have been killed by the Junta and 700,000 have been displaced since then in a protest against the coup known as the “Spring Revolution.” What not all may be aware is that this was not an isolated instance and that the military has been cracking down on their people for years, even decades. Against the physical violence that never seemed to stop, the people of Myanmar stood up 33 years ago, known as the 1988 uprising.

Nyo was in the middle of the 1988 crackdown that had Burmese people fleeing out of Myanmar, contributing to the Burmese diaspora we see today, including in Japan. The 1988 uprising was brutal. The 1988 uprising caused political disruption and polarization in Myanmar and forced Nyo to leave his country despite his privilege of belonging to a middle-class family. Throughout his journey of fleeing from Myanmar to Japan, he went through numerous struggles.

“Local residents and college students got into a fight. Then the military starts shooting at them with a gun. Students are dead on the streets. That’s the first day.”

1. Myanmar Before

For decades, the people of Myanmar have suffered from dictatorial military rule since the country’s independence from Britain in 1948 shortly after the end of the Japanese occupation, and faced several deep conflicts, including fatal violence and widespread poverty. There was a single party in Myanmar that held the utmost power in the state. Everything belonged to the government including; the police, fire station, firms et cetra. The members of the party and the public servants were in charge of tracking citizens’ daily activities. Nyo explains that whenever people go out, they are obligated to report the duration, location, and whom they will be hanging out with. The submission of their identification card was needed to gain approval to move around. Whenever the citizens violated the state rule, they were either fined or imprisoned for a month. No one had the right to oppose government policy due to the suppression of socialism by the military.

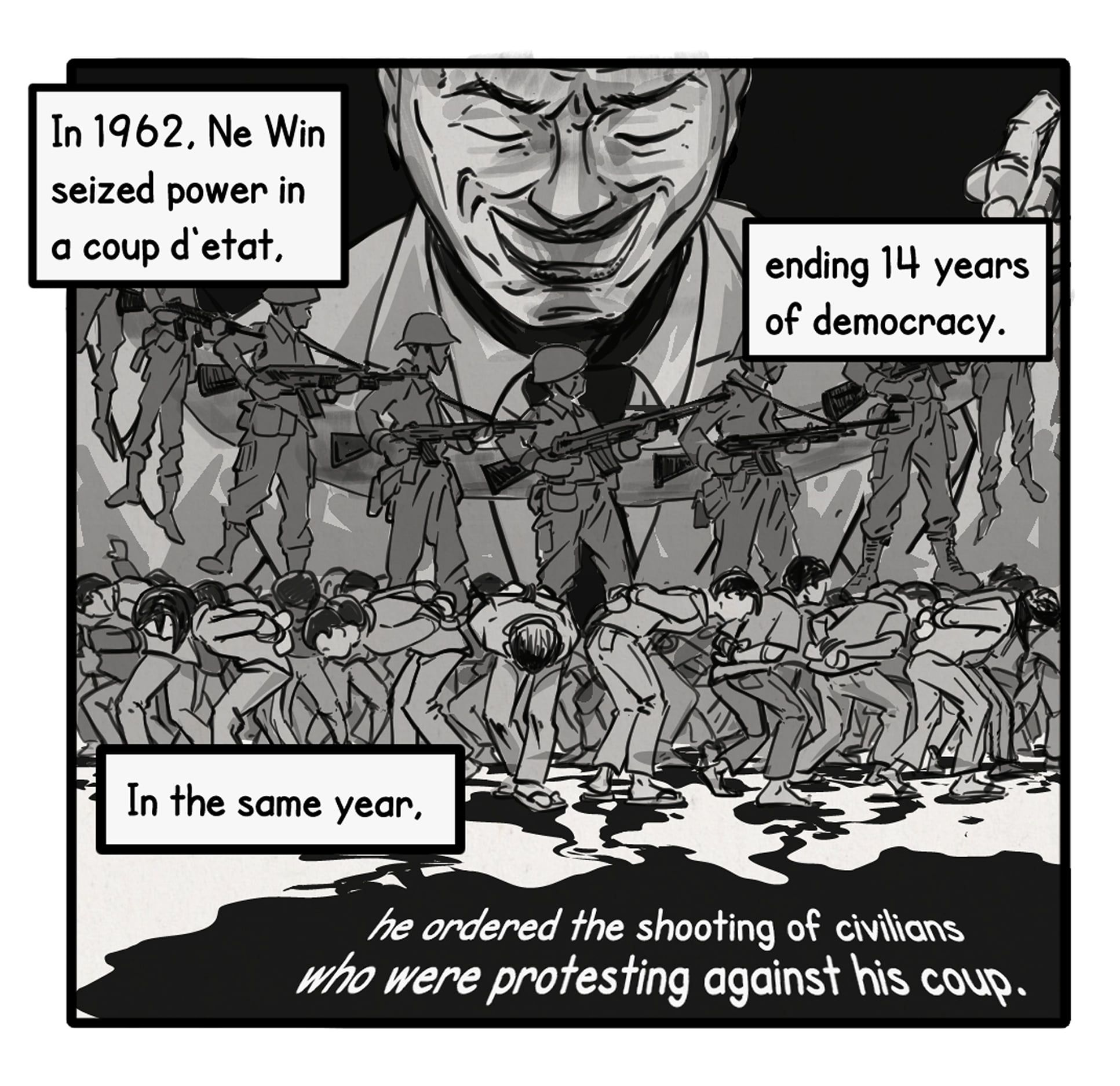

The nation has been through three phases of oppressive military regimes: from the most recent to the oldest, dictatorial power since the coup d’état involving Aung San Suu Kyi in 2021, a junta under Than Shwe from 1992 to 2011, and a dictatorship under Ne Win from 1962 to 1988. Between these periods, however, hopes of democracy were brought to the people of Myanmar. A recent example is the 2011 reforms, where although still backed by the military, the government launched a series of changes that aimed at political, social, and economic development. Another remarkable example is the student-led uprising that took place in 1988, commonly known as the 8888 Uprising as it occurred on August 8, 1988.

Note: English subtitles are available for all videos on this page.

Click here to see how to put on subtitles.

The background of the 8888 Uprising was the severe economic stagnation under the 22-year dictatorship of Ne Win that began in 1962. Under socialist economic policies such as the nationalization of major industries, production had stagnated and the value of the currency had declined. In 1987, Myanmar was recognized as a Least Developed Country (LDC). Japan had been providing financial assistance to Myanmar since 1968, but this was suspended the same year due to overdue debts, and financial assistance from other countries was also cut off as Myanmar became isolated under the military dictatorship. The Burmese-style socialism, known as the “Burmese Way to Socialism” by Ne Win, led to the end of democracy, economic corruption, price hikes, and its people suffering from extreme poverty. All these factors led to the 1988 uprising.

“The economy is bad, No work after college, I can’t even study college-level studies. Citizens’ anger makes the country worse.”

Nyo argues that the “Burmese Way to Socialism” was a complete failure, lowering citizens’ living, economy, and education standards. Especially, he thinks that young Burmese students were the ones who were most affected, dragging them into a world without rights or freedom where they could not see their future. In Myanmar, it was the intelligent university students opposing the military administration. Thus, the military took measures such as to hinder students from going to school, motivating them to enjoy amusements such as; going to the movies, zoos, and parks with friends during school hours. Nyo claims their goal was to prevent young citizens from gathering up and forming a student union to fight against the military. Even the Burmese government kept schools and universities closed in order to prevent future uprisings.

Because Nyo was one of them, he shared the pain and regret of missing out on his valuable life opportunities during these politically corrupt times. Nyo, who majored in mathematics at university, had the intelligence and the experience of working as a civil servant, but could not find a good job after graduation. Myanmar was no longer a place for Nyo to take care of his wife and kids.

2. 1988 Uprising

The uprising took place in Rangoon (today known as Yangon) and was initiated by Burmese students, Buddhist monks, civil servants, and ordinary citizens who had long been accumulating anger and hatred toward the one-party military regime. At first local protesters were singing the national anthem, peacefully demonstrating for their freedom and rights. However, the situation turned into turbulence when the military opened fire on the peaceful Burmese people. The Myanmar government controlled the protest by force, killing one student on the first day of the uprising. Four days later after the uprising, dozens of people were shot and hundreds were imprisoned.

Right: Image of Military force (BBC)

Nyo himself saw students being killed on a street by a shotgun and he vividly remembers this raw and traumatizing situation. When students found their university gates locked and security forces in place to prevent their entry, students started marching towards the U.S. Embassy. Then the Burmese security forces opened fire on the students and many were shot in their heads in front of the Embassy entrance. Nyo describes this situation as a “barbarous” suppression, having to see many dead bodies of students on the streets.

“They were controlling by force. When you are outside, you will get killed. So there is a lot of video of that. They shot a lot in front of the U.S. embassy, right? They shot the students in the head.”

Soon after the uprising began on August 8, Ne Win resigned on August 12 after 22 years of dictatorship. However, political instability continued and on September 18, a coup d’état brought another military junta, this time led by the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). The violent suppression made Nyo feel very unsafe, feeling as if the military constantly targeted his life. Nyo explains that Myanmar had no such governmental intervention or defense to ensure the security of the citizens from potential threats. Similar to the students involved in the protest, he also had to have his weapons ready in case of a military attack. Especially since he had a wife and two sons to look after, he felt intimidated having to protect them all on his own.

“I had to protect my house from the military force myself. I had a knife and weapons in my hands to defend my own path. It was pretty terrifying living in a place with no police or protection from the government.”

It was during this 1988 uprising that Aung San Suu Kyi, who would later win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, emerged as a symbol of the nonviolent democracy movement. She was a speaker at demonstrations across the country and formed the National League for Democracy (NLD) on September 27 of the same year, but was placed under house arrest by the military junta. The following year, in 1990, the NLD won 81% of the seats in the elections, but the military refused to recognize the results, and Suu Kyi remained under house arrest until 1995. Nyo supported Suu Kyi, respecting her politics that aimed at reirecting Myanmar to democracy as many people of Myanmar wished for. Comparing her, who has suffered more house arrest since then and has been imprisoned since the coup of 2021, and himself who gained freedom in the end, Nyo pleads about how unfair the situation is.

“Including Suu Kyi, they were imprisoned for two years. I am free now but she isn’t.”

Right: A satire depicting Ne Win and Aung San Suu Kyi as both wanted (Chappatte)

Including the citizens, she had limited rights to voice out. Her reputation as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate was a hindrance for her to fight back against the military. While the citizens were able to take risks to challenge the military forces, she was required to maintain the icon as a democratic peace reformist, thus allowing the military to take control of Myanmar.

“Suu Kyi was a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, right? The prize was a hindrance for her. Normal people like me can express our anger like “I will kill you!” towards the military but she can’t.”

3. The Decision to Leave

Myanmar in the 1980s experienced several political riots and major policy shifts. The sudden currency denominations caused a tremendous loss of savings for citizens, as well as tuition savings, to become completely worthless for students in college. Although Nyo’s family during this troublesome time were fortunate enough to still have savings, the country’s economic instability still affected their living. After witnessing the devastating change in Myanmar’s government, Nyo decided to leave the country and flee to Japan to support his family.

Throughout the apprehensive history of Myanmar, Nyo’s life-changing decision was made back in 1991, just barely in his 30s. While Myanmar was under despotic rule, citizens were still permitted to leave the country as long as they could afford enough money and obtain the correct documents. As stated by Nyo, Myanmar’s passport at the time, in the 1990s, authorized citizens to travel to five countries: Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and limited states in the United States. Due to economic deprivation and humanitarian crisis, thousands of civilians had decided to seek refuge across the border of Myanmar.

Nyo was one of them, and his initial plan to provide for his family was to become a ship worker. After thinking through what jobs could offer him a high earning, Nyo considered leaving the country and learning to maneuver a ship. This job, according to him, was very popular among the younger generations during the 1990s, as one could potentially acquire enough profit to afford a car or a new house, especially when the job was carried in a different country.

Despite the good wages that working on a ship could offer, Nyo’s final decision was to flee to Japan. However, this choice was not easy. By 1991, when he left Myanmar, his two sons were still very young; with the older one being six years old, and the younger one being only three. Nyo was worried and hesitant at first, but with the push of his wife and family, he was able to make his decision. In addition to his savings from working as a civil servant, he received some financial support from his parents to fund the travel to Japan.

“I was lucky to be born into a middle-class family.”

Nyo shares that, originally, he only intended to stay in Japan, a place where he could support himself while fleeing persecution, for three years. “My wife told me, ‘Do your best for about three years’. I left the country believing that everything, like politics, the economy, and myself as a person, would change within that term”, Nyo described. At this point, he and his family expected that in three years, the condition in Myanmar would improve, and Nyo would come back with more earnings to provide for his family. However, this was merely the start of his long 31-year journey in Japan.