“I will do my best in whatever I have in front of me at the moment. That’s all I think of.”

Born in 1959 in Myanmar, Nyo first set foot in Japan on December 12, 1992, hoping to return home and reunite with his family soon after his country was emancipated from the oppressive military regime. Yet, that day has never come. In the blink of an eye, he has been staying in Japan for over three decades. As the seasons come and go, his two sons have grown up and married, his wife has aged, and his parents have passed away. He was never a part of these moments.

So much has changed yet not much has improved during his 31 years in Japan. Even to this day, he still has no access to health care, work permits, and proper housing, placing him in a perilous situation under COVID-19. He was rejected once for his refugee application 12 years ago. He applied for it again in 2021, but the result was the same.

Despite all the setbacks and obstacles that he has been facing, Nyo still manages to get up and continue pushing the boulder up the hill, accepting and living his Sisyphean fate. He is a strong-hearted and open-minded man with integrity, tolerance, perseverance, and responsibility, which are core personality traits that he developed during his years in Myanmar. To better understand Nyo as the person he is today, this section explores Nyo’s upbringing and experiences during his childhood, teenage, and adulthood years in Myanmar.

1. Childhood and Teenage Years

Note: English subtitles are available for all videos on this page.

Click here to see how to put on subtitles.

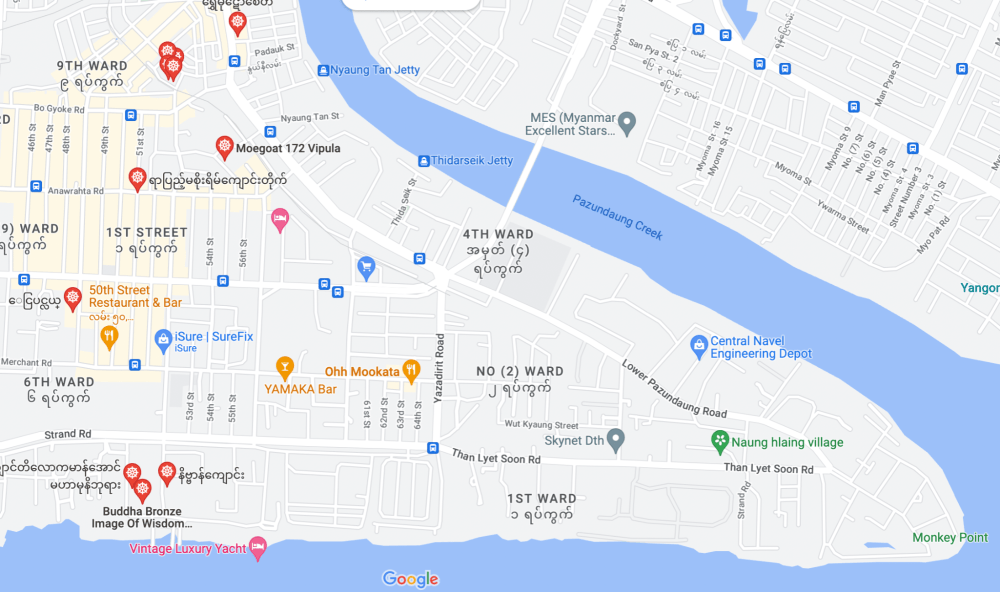

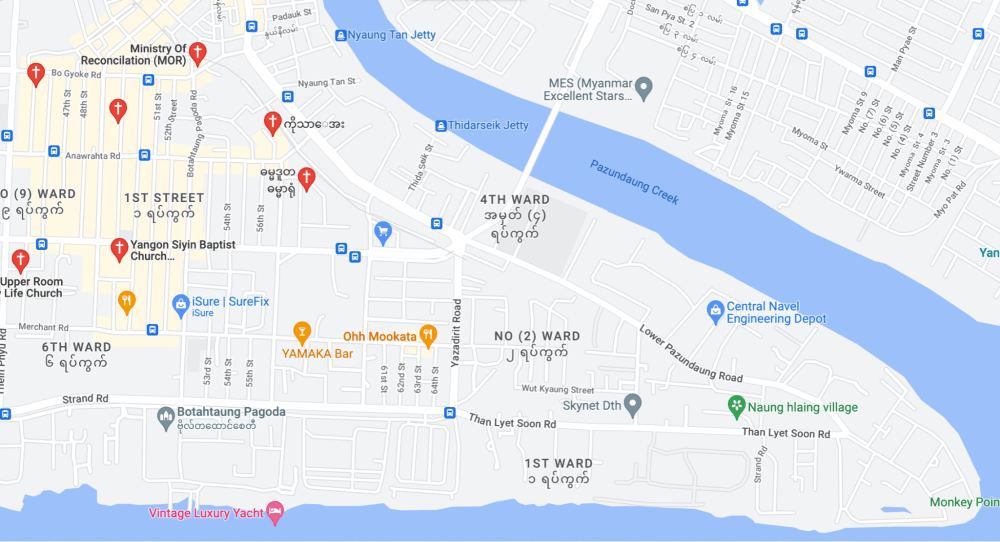

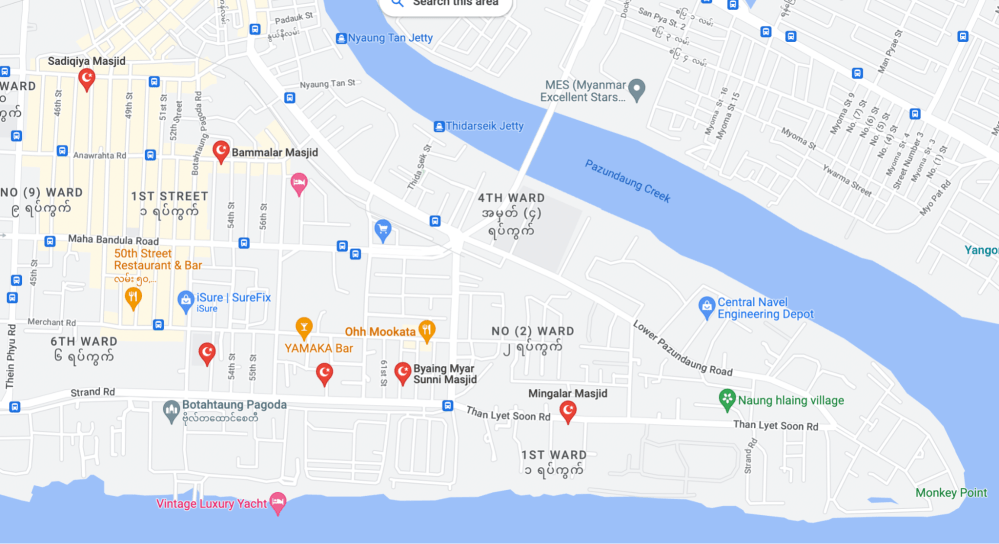

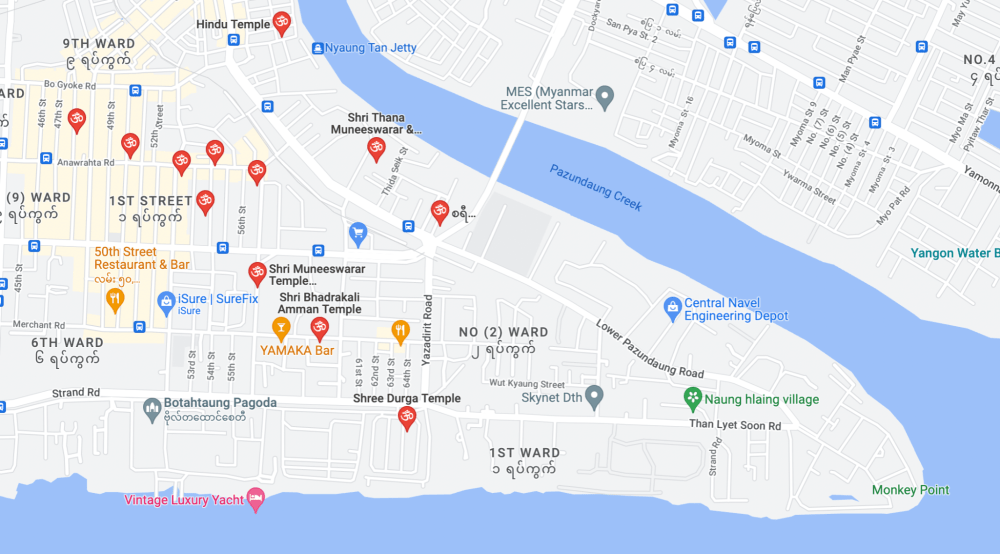

Nyo grew up in a family of seven and a middle-class household in Yangon City: the largest city and the most important commercial hub in Myanmar. To the south of the city lies Botataung Township, a culturally and religiously diverse downtown at the confluence of the Yangon River, where he grew up with friends from different religious backgrounds. The big family of seven was sustained by his father’s small rice factory in the countryside and his mother’s clothing store in town, allowing Nyo and his brothers and sisters to live in a comfortable house and go to one of the best schools in the country. This starting point, where he was able to receive a good education and cross paths with people from various religious communities, allowed Nyo to develop an open-minded and growth mindset during his childhood and teenage years.

Right: A map of Botataung Township (Google Maps)

1.1. A Good Starting Point

“I went to a Catholic school even though I was a Buddhist. The school was chosen by my mother. It had nothing to do with religion. She just wanted me to go to a good school, hoping that I could become a proficient English speaker when I grow up.”

Primary school enrollment rates remained low in Myanmar during the ’60s and ’70s, with only about 60% of children receiving primary education. Thanks to Nyo’s family background, he was able to attend school from a young age, but it was not any kind of school. It was an elite school. Myanmar is a country where patriarchal values and norms are prevalent. Therefore, it is not uncommon that parents put more time and money into nurturing their sons and fostering their son’s development.

The same applied to Nyo’s parents. In hopes of paving the way to a bright future for his eldest son, Nyo’s mother invested much in Nyo’s education, allowing him to study in an elite Catholic school, which was prohibitively expensive to most Burmese, from elementary to high school. The school was one of the most competitive schools in Myanmar best known for its English education ever since the country’s colonial past. Even though Nyo failed the elementary school entrance exam on his first try, he eventually entered with his younger sister a year later with his mother’s encouragement and support. This starting point in an elite Catholic school further increased Nyo’s chances of receiving a college education and working as a government worker in the future, which were both important turning points in his life.

1.2. An Open-minded Omnist and Cosmopolitan

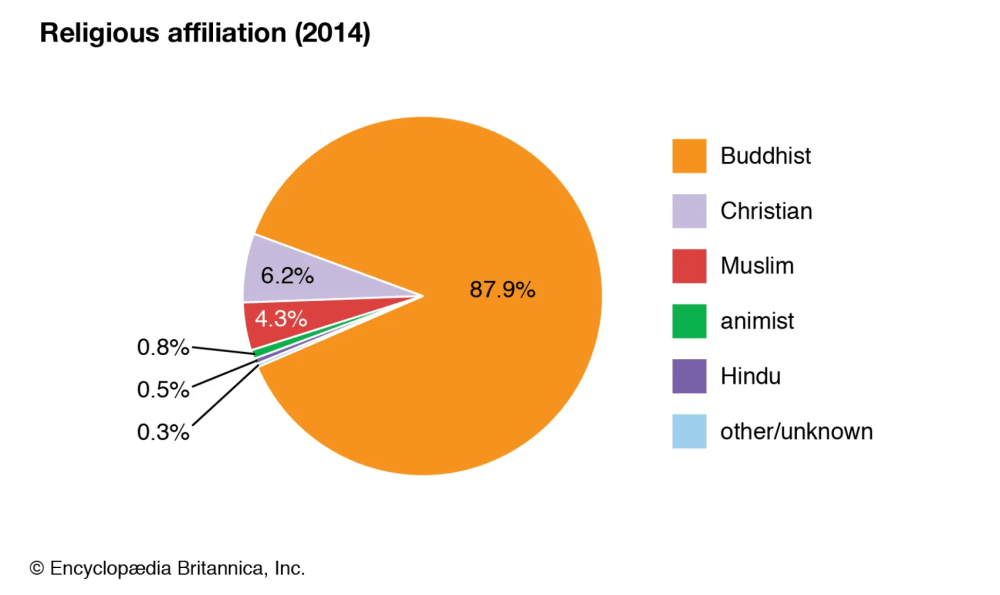

Nearly 90% (approximately 49 million people) of the Burmese population are Buddhists and Nyo was no exception. He was born into a traditional Buddhist family, where his grandmother would take him to the temples to pray, celebrate festivals, and practice rituals on full moon nights since he was a child. As the years passed by, however, he started to think outside the box of Buddhism, gradually becoming an omnist who respects all religions and a cosmopolitan who embraces diversity and inclusion.

The transition from a Buddhist to an omnist did not happen out of the blue. From Catholic churches, and Hindu temples, to Muslim mosques, Nyo was exposed to various religious beliefs when growing up as a Buddhist in Botataung, and his participation in various religious scenes and events was a large part of his everyday life.

After saying goodbye to the priests and nuns at the Catholic school, he would sometimes witness the slaughtering of cows and the consumption of beef (the Islamic ritual called Dhabihah) among the Muslim community at a mosque on his way back home, just a block from his house. One more block away was a Hindu temple, where he would hang out with his Hindu friends and participate in their wedding ceremonies decorated with sacred banana leaves. Coming back home, he would sometimes go to Buddhist temples and chant the sutras with his grandmother.

“Be it Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism, I want to be friends with everyone.”

Looking back, it was because of Botataung Township’s diversity in faiths, ethnicities, and cultures that sowed seeds of tolerance and curiosity in Nyo, making him an open-minded and inquisitive person since childhood. He genuinely wants to be friends with everyone, regardless of their backgrounds. He strongly believes that everyone is born equal, transcending boundaries of religion, nationality, and money. This upbringing and childhood experience significantly influenced how he treats people and how he navigates his life according to the religious teachings that he finds sound and sensible, whether they are from Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, or Islam. His positive and open attitude towards religion also helped me go through difficult challenges during his years in Japan as an asylum seeker.

2. Adulthood Years

Nyo’s adulthood years in Myanmar were full of excitement and bittersweet memories. This was the time when Nyo gained a clearer vision of the life he wanted to live, one that was sincere and authentic. He was committed to every choice he made, living his values of honesty and responsibility, working hard as a civil servant, eloping with his first girlfriend who later became his life partner, and becoming a father of two. This section tells stories about his life after turning 18 and before departing for Japan when he was 32 years old.

2.1. Integrity and Ways of Living

“Money… It can destroy people if you put too much faith in it.”

“People are mostly ‘kids’ before they reach the age of 18,” says Nyo. “I didn’t think much about religion and my life when I was a kid going to the temples with my grandmother.” When Nyo reached the age of 20, he became disappointed in the Buddhist monks’ corruption in the country, which pulled the trigger for his decision to abandon his Buddhist identity.

The source of the corruption was the Burmese people’s large donation to monks. Despite the low GDP growth rate, Myanmar is placed second in the willingness to make donations among 160 countries in the world. Using people’s faithfulness towards Buddhism, monks started to coax people into making donations to help them build Buddhist temples and monasteries, and some even joined hands with the military regime. As a practicing Buddhist since childhood who strictly followed, and is still following, the Buddhist teaching of The Five Precepts, Nyo strongly condemned the monks’ act of lying.

Right: The Five Precepts of Buddhism (Quora)

From Nyo’s voice, it is evident that he is furious about the monks’ manipulation of people using money and blatant lies about how a faithful and good Buddhist makes donations to help build Buddhist temples. “That is fake Buddhism,” shouts Nyo emotionally. “When I visited the temples with my grandmother, everything was normal. Joining hands with the military, they [the monks] have become more and more corrupted as I grew up.”

Seeing how monks have strayed away from the “real Buddhism”, Nyo decided to stop identifying himself as a Buddhist. As someone who always stays true to himself, Nyo did not see the value and meaning of identifying with a religion that is now misrepresented and misleading. However, this does not mean that Nyo is a non-believer of Buddhism or an atheist. His life values are largely based on the correct Buddhist teachings that his grandmother had instilled in Nyo since he was a child, such as acknowledging the impermanence of life, treasuring every encounter, and living the present moment. These values together have been guiding Nyo’s life, making him an honest and authentic person who sees value in learning from everyone he has crossed paths with.

Moreover, with his childhood experience interacting with people of different religious backgrounds, Nyo can appreciate and respect different ways of living, hoping that everyone can be treated with equal respect. In this sense, his belief in cosmopolitanism makes him more “human” than many others, as he lives in alignment with his core value of embracing diversity while constantly exploring the plurality of life.

“It’s not about throwing away my own culture. It’s just that I no longer identify myself as a ‘Buddhist’ anymore. ‘Everything Buddha says is correct; Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism are wrong.’ I don’t have that mindset.”

Having escaped from Myanmar’s military junta and realizing the importance of peace and equality, Nyo sincerely hopes that people can appreciate and cherish our shared humanity and be aware that more similarities unite us than differences that divide us. “To live in a world where people are respected and treated fairly.” This is his message.

2.2. College Student in the Day, Civil Servant at Night

After entering college at the age of 19, Nyo started working as a civil servant at a local ward office. He was working from 7 to 9 PM, stamping travel permits for residents for five years. “In Myanmar, people cannot travel freely from place to place,” says Nyo. “This is how socialism functions.” Nyo, who came from a middle-class family, did not have to do a part-time job to support his day-to-day life. The amount of pocket money he received from his parents was way higher than his salary as a government worker. However, with his determination to contribute to his country, Nyo still worked hard in this job until he graduated from university, even though he only received about 20,000 yen in total during the five years.

“I only earned about 20,000 yen during the five years [as a civil servant in Myanmar]. Although I also had the experience of earning 300,000 yen in Japan, I see more value in the 20,000 yen than the 300,000 yen. Being able to contribute to my country. That was a valuable experience in my life.”

This quote epitomizes Nyo as a diligent and self-motivated person. To Nyo, the 20,000 yen earned from his job as a civil servant in Myanmar represented his devotion to his country, while the 300,000 yen earned during his time in Japan was more about surviving. Moreover, being brought up in a well-off family, Nyo’s job as a civil servant in Myanmar represented his milestone for becoming an adult, since he did not need to fully rely on his parents financially and was able to spend his own hard-earned money. Therefore, he finds a stronger sense of purpose and self-worth in the civil servant job despite its low salary, putting much effort into his work. His diligence and good work ethic were influenced by his father’s teaching:

“‘No matter what you do, never give up halfway. I want you to do your best from the beginning to the end.’ This is what [my father] has taught me.”

To this day, Nyo still lives by his father’s words, allowing him to persevere and overcome obstacles working in cleaning in Japan. Nyo is not interested in the material aspects of life, such as money and goods; he puts more importance on enhancing his inner world and finding meaning in the work he does and the people he encounters.

2.3. One and Only: The Runaway Couple

“I only had one girlfriend. I’m actually a very faithful person.”

Nyo may seem like a shy person at first glance, but he is very loyal to the people he loves and cares about and is one of the most sincere people one can ever meet. Nyo started dating his first-and-last, one-and-only girlfriend in his life when he entered college at 19. His girlfriend was his neighbor, who was two years younger than Nyo and was living in the same community in Botataung Township, and they had known each other since childhood. However, Nyo’s mother was against their relationship in the beginning, as she was hoping that Nyo could focus on finishing college and getting a stable job before going into a relationship.

“[My mother] was angry! She even published an article in Myanmar’s newspaper saying, ‘He [Nyo] is not my son.’”

Nyo rarely shows much emotion when talking, but he is upset about his mother’s disapproval and can tell a vivid story about the hardships and frustration he endured and experienced when dating his girlfriend at the time. While Nyo’s girlfriend came from a far more affluent family than Nyo, she did not receive a high school education. This was the main reason why Nyo’s mother was opposed to their relationship since she thought that the girlfriend was not an ideal partner for Nyo. Yet, young Nyo did not give up. The couple continued going out in secret for about a year despite the arguments coming from both families. “Love is love, and school is school. What’s the problem with having a girlfriend in college?” speaks Nyo emotionally. “I didn’t do anything wrong. What’s wrong with choosing my own path?”

Eventually, the couple eloped together and left all the quarrels behind. To Nyo, he did not choose his girlfriend over his mother but rather he made a decision that appeared most reasonable to himself at the moment; from a rational point of view, he genuinely thought that he was able to continue pursuing his college education while dating and saw nothing problematic with that. He firmly believed in his decision, and he was ready to take full responsibility for his decision. Coming back home, Nyo and his girlfriend announced their marriage in 1980. They had their first son four years later, officially marking an end to the two families’ dispute and the beginning of a new chapter in life.

This love story, which to some degree resembles the love story of “Romeo and Juliet,” between Nyo and his wife shows Nyo’s faithfulness and commitment towards his one-and-only life partner, whom he had not seen for the past 21 years. Fortunately, Nyo’s wife was able to make peace with Nyo’s mother after the birth of the first son, and their relationship has changed ever since. When Nyo’s mother was still alive, she treated Nyo’s wife as her own daughter, as she was the only person who was always by her side when she most needed it. Therefore, Nyo is grateful that his wife was able to stay beside his mother before she drew her last breath two years ago due to a sudden heart attack, and that was the only way he could repay his debts to his mother. In this sense, while living under the fear of being deported back to Myanmar and the uncertainty of life and death in Japan, Nyo sees his wife as an important mental support that encourages him to persevere despite the setbacks in life. Continuing until today, Nyo still works hard and tries to live fully before he can reunite with his wife, and that thought has never changed over his past 31 years in Japan.

2.4. Family, Responsibility, and Freedom

Nyo was only able to experience real fatherhood for seven years, as he left for Japan when his eldest son was 7 years old and his second son was 3 years old. While he could not witness his two sons growing up and fully participate in their childhood, he did set up a life principle for them: “taking responsibility in every choice you make”. Nyo has always hated to be rejected and turned down since he was a child; he hated it when he could not buy the toys he wanted from his grandmother and when his relationship was disapproved by his family. Therefore, Nyo hoped that his children could always choose freely while also taking responsibility for the choices they made, just like when he decided to leave Myanmar and embarked on an arduous journey in Japan to live in freedom.