Note: English subtitles are available for all videos on this page.

Click here to see how to put on subtitles.

Every refugee has his or her reason for leaving their country. As a consequence of Myanmar’s changing politics, Nyo made his decision to flee to Japan, not only to support his family through the nation’s economic instability but also because he strongly disagreed with the oppressive regime of Myanmar. In 1991, he left his country by himself in hopes of starting a new journey. However, his life as a refugee in Japan was much different than what he had expected.

“In Japan, you’re free to say what you want, and write what you want, and I love that. That’s why I won’t go back to Myanmar.”

1. Arrival to Japan

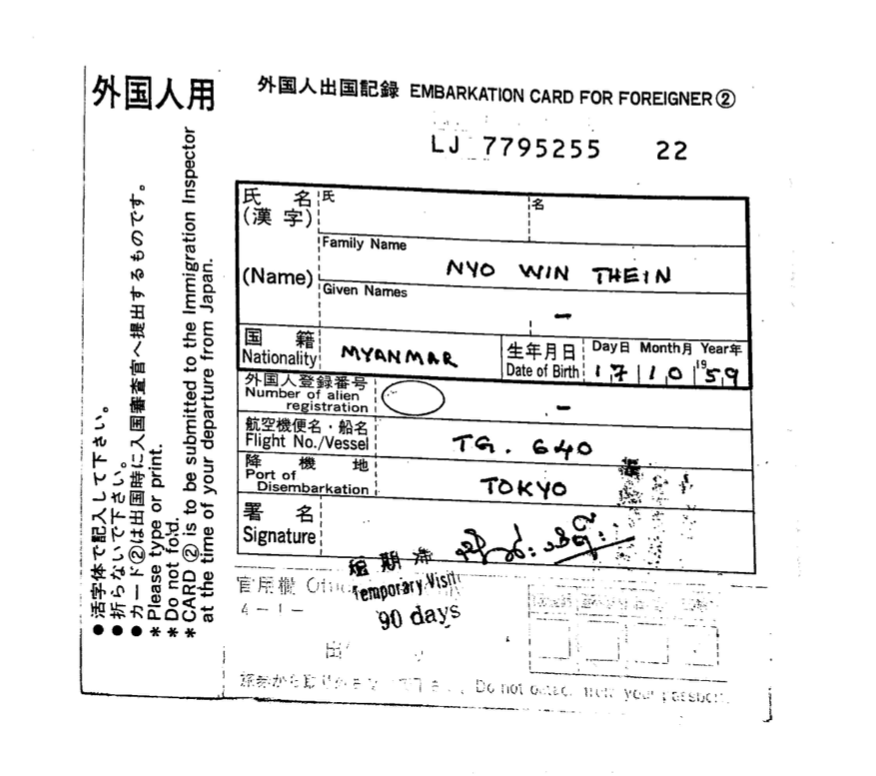

On December 12, 1991, everything started. After a long flight of nearly six hours from Bangkok, Nyo finally arrived in Japan to start a new chapter in his life. His first “trip” out of the country was surely impactful, but little did he know back then, that this would last for over three decades. Nyo left Myanmar alone, leaving his wife and kids behind. He left with the hope that someday Myanmar will restore democracy in its own political system. He decided not to bring his family along since he knew that his life in Japan would be too uncertain to take care of his loved ones. Neither Nyo himself nor his family members possessed a visa to live in Japan so it was not feasible for them to travel in the first place. He somehow managed to flee to Japan with the money that he and his parents saved.

Traveling to a different country was a new experience for Nyo. Moving once from Yangon (the capital of Myanmar at the time) to Bangkok, then taking a six-hour flight to finally reach Narita International Airport in Japan, Nyo’s journey was an exhausting start. However, his prime issue upon his arrival was the language barrier. Nyo could not speak Japanese, since it was not a prevalent language back in Myanmar, but none of English as well. The only word he was confident within both languages was “Yes.”

Due to his inability to communicate, Nyo aroused the police’s suspicion at the airport and ultimately stopped to answer several questions, some regarding his luggage and reasons for coming to Japan. When asked to show his documents regarding his visa status, Nyo repeatedly answered “Yes” or tried to make sentences by putting together any other words he knew in English to answer matters that he could not understand. The atmosphere of this situation was intense, for if he answered their questions wrong or made them skeptical about him in any way, Nyo could have been sent to the detention center immediately. However, to his surprise, this language barrier helped him avoid such an outcome. Nyo light-heartedly explained that the police eventually assumed he was harmless, and gave up on asking him further questions.

Nyo knew fleeing to a completely different country by himself was going to be tough. Upon his decision to leave Myanmar, he had to convince himself that he was starting a new life, as a new person, to work hard and someday reunite with his family. Nyo thought he was mentally prepared for anything that life would throw at him from that point. However, after leaving, he realized how much he missed his family. Although Nyo is not the type to get emotional, he cried on the night he arrived in Japan thinking about his mother; this was the first and last time he shed tears in Japan.

Truthfully, Nyo wanted to stay close to his family. Yet, with the severe regime that Myanmar was under, which he strongly disagreed with, he simply could not return to his homeland. Though conflicted between wanting to be with his family and wanting to seek new opportunities at a new location, Nyo was able to stay strong after remembering his “three-year” promise to his wife. In hopes that Myanmar’s government system would change for the better, he managed to endure the loneliness and work for his family.

2. Legal Crossroad

Nyo had a long journey waiting ahead of him. However, to start this new chapter in his life, he needed to make sure his preparation was perfect. To first leave his country, Nyo had to obtain a visa. Having a passport was one good factor, but it is not equivalent to having a visa. In particular, Myanmar’s passport still allows visa-free travel to a much more limited 92 countries, the smallest number in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), compared to 194 countries that the Japanese passport does. In the 1990s when Nyo came to Japan, Myanmar’s passport only permitted travel to five countries including Japan.

Since Nyo’s passport did not grant him visa-free access, he was required to submit a Letter of Invitation from someone in Japan to accommodate a place for the applicant to stay. To fulfill this requirement, Nyo received help from his uncle’s friend, Hamano. “Back then, it was very easy”, Nyo described. “I couldn’t read kanji, but the letter said something like, ‘Come visit Japan!’” Although Nyo did not personally know who Hamano was, nor had met him, he mentions that he was thankful for allowing him to take the first step needed for his journey.

As Nyo explained, receiving a tourist visa in Myanmar was easy. The real problem came after his arrival. Once his 90-day tourist visa was over, his next step would have been to seek other legal options that permit him to remain in the country. Japan has been a signatory to the Refugee Convention since 1982, meaning the state has committed to granting legal status to those who are recognized as refugees. Refugee status, as defined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is, “The legal or administrative process by which governments of UNHCR determine whether a person seeking international protection is considered a refugee under international, regional, or national law,” or in other words, anyone who is acknowledged as a refugee under the law. Those under this category are essentially treated the same way as a regular Japanese citizen.

Nyo is a refugee from Myanmar, who had to flee his home country due to the ongoing political oppression. However, he did not apply for refugee recognition at this point. Several factors help us understand this action of his. First and foremost, the important context here is that Japan was still at its very early stage of refugee recognition; it had only been 9 years since Japan started accepting refugees when Nyo arrived in Japan in 1991. In fact, the number of applicants that year was 48, out of which only one was granted refugee status. The premature structure for accepting refugees was also the case for civil society. Support from civil society organizations, which play an important role in the lives of asylum seekers who are given minimum support from the government, was lacking. The Japan Association for Refugees (JAR), the main organization supporting refugees in Japan today, did not exist until 1999, for instance. Unlike today, when the Internet has made instant access to a vast volume of information possible, it was much more difficult to obtain any information on refugee recognition in Japan on his own. Therefore, not only did he not know how but even had the idea of getting legally recognized as a refugee in Japan at that point.

“When the siren came wailing, I was all, ‘Did the grandmother next door call an ambulance? Was there a fire? Is the police coming?’ My heart would beat fast.”

Shortly after managing to find a job as a cleaner, he became an overstayer. Looking back, Nyo remembers his heart would beat fast every time he heard the siren of the emergency vehicles. Although he was able to get a job, he describes his life as “There was no guarantee for him to return to his bedroom at night.” Since he did not possess a legal immigration status, he was constantly at risk of being caught by a police officer. However, since Myanmar was still under the control of the military, it was not the place where he would want to return. He knew the risk of being caught. Nevertheless, unofficial foreign workers such as Nyo at the time were a significant part of the labor force that supported the Japanese economy during the great economic bubble from 1986 to 1991, known as the “Bubble Economy,” and the stagnation that followed after its burst.

3. Unrecognized Contribution Under the Bubble

“When you watch the NHK news channel on bubble economy, you see people enjoying wine that costs over 2 million yen. That’s what it was like in Japan.”

The burst of the bubble economy that had been going on since 1986 is generally considered to have started in 1991. However, when Nyo came to Japan that year, the bubble period was still effectively going on. He still remembers how surprised he was to see people drinking wine that cost two million yen a bottle on a program by NHK (public news channel) on TV. Having grown up in Myanmar amidst violence and suffering, everything about the full, rich, and peaceful life of the Japanese people felt new to him.

“So I worked for the 3D jobs. Just me.”

As the Japanese economy grew, Japanese workers were not eager to work for low-quality jobs which were categorized as “3D” (Dirty, Dangerous, and Demanding) jobs, or known as “3K” jobs (Kitanai, Kiken, Kitsui) in Japanese. While Japanese people were working for office jobs, Japan filled in many unofficial foreign workers to the 3D job vacancy, such as dishwashing tasks at the restaurant. Under the labor shortage during and after the bubble economy, desperate employers resorted to such foreign workers, documented or not, and the police turned a blind eye to the “cheap and disposable” labor.

(EE Times Japan)

In fact, 1991, the year Nyo arrived in Japan was at the peak of the number of those known to be unofficial foreign workers, tripled from the beginning of the bubble economy. Within the 90 days that his tourist visa was valid, he got a job as a cleaner. When asked how he found work so quickly and informally, Nyo answered it was easy, confirming that a lot of companies including the one he worked for were understaffed then due to the bubble economy. The employers simply made a copy of the front page of his passport, and he was ready to work. “I still remember,” he further accounts his first days: “This man trained me for three days and then he was gone. I asked where he went, and [it turns out] I was hired to replace him. He was 82.”

As Nyo takes pride in himself as having been the “best worker,” he put his very best in this job, establishing a great relationship with all of his supervisors. “Back then, Japanese people didn’t really know about visas. I swept, wiped, and cleaned thoroughly. They recognized my work and protected me,” he explains. His hard work was indeed acknowledged by the company, and just after a year, he landed jobs in the same company’s production department that he was more interested in. Nyo worked at the company for 17 years, and he spoke with gratitude as he remembers his time there, “I was taken care of.”

Nyo spent the ’90s as one of the unsung heroes behind the bubble economy and the severe recession that followed its burst. Despite his contribution, for more than a decade, he was not able to do anything in his name and feared every police siren as other legal options than overstaying did not seem available. As mentioned, it did not occur to him to apply for refugee status being in the underdeveloped legal and civil structure, and he already had found a job at a company in Saitama, near Tokyo, which provided him with a means of survival. For Nyo, whose priority was to make ends meet without being exposed to the risk of political persecution, his immediate action was keeping the job, staying low profile, and remaining the status quo.

However, a turning point came to his life in the early 2000s. He looks back at the time and explains, “Japan was filled with unofficial foreign workers in the 90s, but you know what happened on September 11, 2001, in New York in America? Then Japan thought it was dangerous to ignore all those overstayers that they did not even know who they were.” In fact, the Japanese government implemented stricter immigration control and deportation procedures as part of the plan to lower the number of undocumented migrants in 2004.

By the year 2004, refugee applicants had increased to 426, and 15 were accepted. Even though the recognition rate was still very low, the legal and civil framework had become more established. Amid the crackdown on unauthorized residents, Nyo became aware of the opportunity to be recognized as a refugee that he had always been and filed the application in 2004. However, his claim was rejected. He appealed against the decision and even took it to the Supreme Court, but it was never overturned. Not having any other choice, Nyo was to continue to live in precarity in Japan where he had long built a life, until one day in 2008, he finally caught the police’s attention which resulted in him being detained by immigration.