1. Detention Center

In 2008, Nyo was taken to the detention center when he was wrongly accused of stealing his neighbor’s bike. Though he quickly accepted this fate, he explained that he was afraid every night because he could have been deported at any time. At the detention center, he had several visitors coming to see him every day, including the lawyer Watanabe-san. Thanks to his help, he was able to leave the detention center in 25 days, which is considered short given the prevalence of long-term, indefinite detention. Nyo also had enough savings from his previous job, where he worked for 17 years since he came to Japan in 1991, to pay the fee to get out of the detention center, which was 300,000 yen.

There are several reasons for a refugee to be put in a detention center. In most cases, it is when the immigration “has a reasonable cause to suspect that there are grounds for deportation,” such as illegal entry to the country or violation of the terms of their status of residence including overstaying. However, under international law, the detention center should be used as the last resort and is supposed to have a suitable reason to do so.

Note: English subtitles are available for all videos on this page.

Click here to see how to put on subtitles.

After Nyo’s 90-day visa had expired, and ultimately became an overstayer, he lived in constant fear. “There’s no promise that I will be back in my bed the next night,” says Nyo. Unfortunately, one night in 2008, he was suspected of stealing a bike by the police. He figured that he would be taken to the detention center, but was rather calm and just accepted it because according to him, that is what a man should do. Nyo is very strong-willed and is a positive thinker. Even when entering the detention center, he compared it with what a jail in Myanmar would look like and decided it was not as bad.

Usually, when someone is describing the detention center, it is often negative. Although Nyo’s experience there was not necessarily pleasant either, he did get along with other refugees there, and he still kept in touch with some of them over the Internet. According to him, he met several other refugees from Myanmar, in addition to other countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. On the 9th floor of the Shinagawa detention center, where everybody’s rooms were, Nyo spent his time with his roommates by playing cards. Since the refugees he met came from different parts of the world, and because most of them could not speak Japanese well, it would be typical to assume that communication was a problem. However, as Nyo explained, they took that issue to a positive one. In their free time, they studied Japanese together, played cards with rules from each of their homeland, and sometimes discussed rather serious topics like religion and politics. It is ironic that Nyo, who struggled with the language barrier when finally arriving in this country, has found a way to enjoy that obstacle in the worst place possible.

Nyo seemed quite popular as well. He explained that during his time in the detention center, he had multiple people come to visit him every single day while he was there. Nyo also believes that as more people he had meetings with every day, the immigration inspectors eventually grew trust in him that he is not a harmful human. Perhaps Nyo gained a lot more trust from the immigration officers than expected. The Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act allows those who have been issued a deportation order to be detained “until deportation is possible,” meaning they can be detained virtually indefinitely. Our other narrators, Sunday and Christopher, also experienced eight months of detention; in some cases, it can take up to several years. Nyo was able to leave after only 25 days, and his case was indeed, very lucky.

“It was only 25 days. I was the luckiest.”

A key way to leave the detention center is to hire a lawyer. Although the chances of actually getting one are low, and most of the time not possible, Nyo was lucky enough to meet Shogo Watanabe; according to Nyo, he is a very famous lawyer who has defended hundreds of refugee clients in the past. Surprisingly enough, Nyo had sent him a letter regarding his situation in Japan before being taken away to the detention center. Since he was an overstayer for about 13 years before getting caught, he explains that going to the detention center was only a matter of time. Watanabe was considerate of Nyo. He even became Nyo’s guarantor when paying for the 300,000 yen for this release, in addition to paying about 80,000 yen for it.

Nyo left the detention center under provisional release (karihoumen), which allows detainees to be temporarily released on grounds such as “health reasons” or “preparation for departure.” He clarified that getting a provisional release was better than being an overstayer. “When I was overstaying, there was no guarantee for coming home, but on karihoumen, I was not so scared at the sight of police anymore.” That being said, restrictions for refugees become much more strict. Some of these include one’s place of residence and the range of activities outside their stay. Under this system, he or she is also restricted from getting employed. Nyo shares the precarity he has faced by not being able to work, “I don’t have a visa, I have had zero work for three years. I am not given a single yen.” His status as karihoumen affects all aspects of his daily life. As he cannot obtain the official registry in the city of his residence known as jyuminhyo, he cannot even sign a mobile phone contract, let alone rent an apartment, under his name. He also could not see a doctor and get treatments for his existing conditions if it were not for the support of the Japan Association for Refugees (JAR). During the COVID-19 pandemic, he was excluded from financial assistance or vaccination, which was based on the mentioned registry system. “I was not treated like a human,” he recalls.

“I cannot do anything under my name. That is the simple example. There is nothing human about this.”

2. Refugees Seen Through Japanese Policy

2.1. Neglected Refugees

Referring back to some historical events and his experience, he passionately appealed to the wrongs of the way Japan has been treating refugees. Nyo is knowledgeable about politics, and he has a full understanding of why the system needs to change. Referring to the ratification of the Refugee Convention by Japan in 1981, Nyo emphasizes Japan “signed a contract to the world, not to itself” to accept refugees. Today, more than four decades later, the number of refugees accepted in Japan still remains a handful. Thousands of asylum seekers who were rejected are left with no choice but to invest more time and money in reapplying while living with minimal support or severe constraints by detention or the terms of provisional release (karihoumen). “They neglected us, politicians. Why? What do they mean?” Nyo asks in anguish.

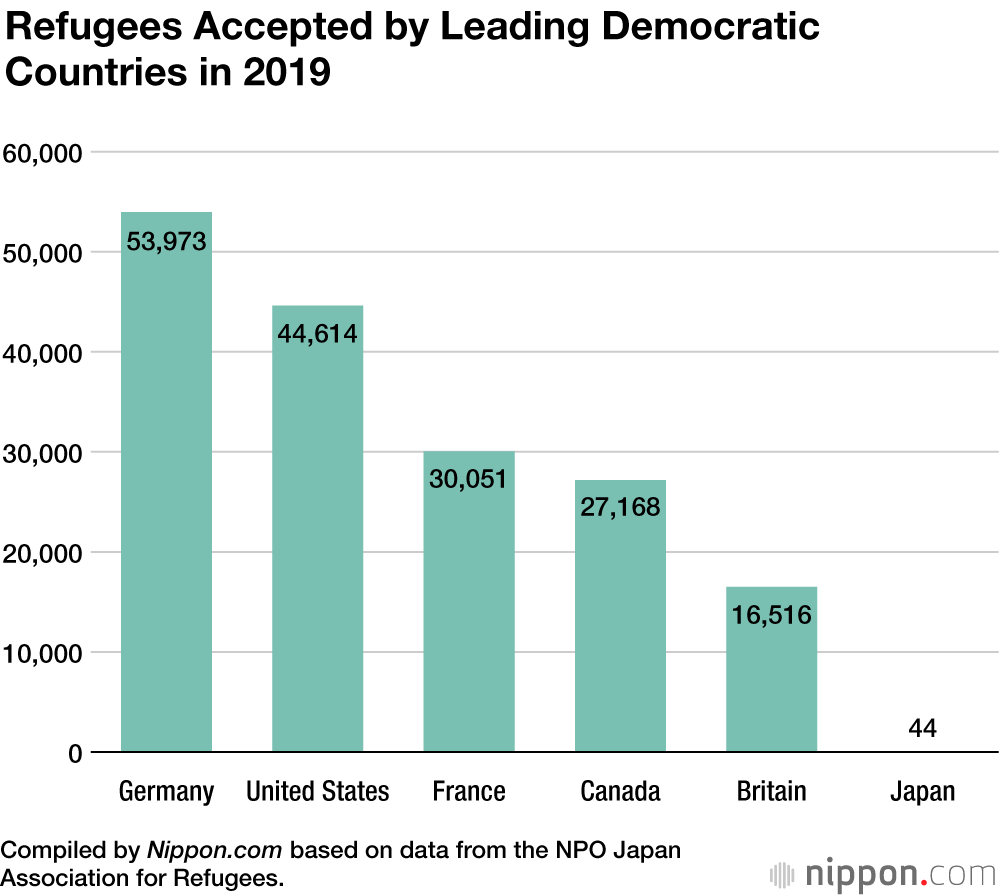

Japan has one of the lowest numbers of refugee recognition in the world. In 2019, for instance, Japan granted the status to 44 refugees while the other democratic nations with developed economies accepted a five-digit number as seen in the graph. Although Japan is beginning to accept more refugees, with the number of recognitions reaching 303 in 2023, Japan’s acceptance rate remains remarkably low from a global perspective; in fact, it has the lowest asylum intake ratio among developed countries.

In 1991, when he first arrived in Japan, the refugee recognition system was still being developed and there was barely any outreach from official or civil sectors, even after ten years of the ratification of the Refugee Convention. It thus did not even occur to him that he had the right and the opportunity to be recognized as a refugee until 2004. The four next years were spent in vain on his appeal against the rejection of his claim, all while not having a choice but to remain an unofficial resident. After getting detained by immigration in 2008, he was left on provisional release (karihoumen) for 13 years until he decided to reapply for refugee recognition in 2021. For 30 years, he lived a “painful” life of not being able to work, access basic health care, or leave home without knowing whether he could return that night. All those years, returning to his hometown and his loving wife in Myanmar was not an option either due to the risk to his safety.

“Neither I nor my family have a visa, so where should we go? You wouldn’t expect it to take 30 years, would you?”

At first, Nyo thought being on karihoumen was better than being an overstayer; at least he was not afraid of being taken off the street. With time, however, he began to see that karihoumen was an endless series of applications, appeals, court cases, lawyers, and paperwork. When asked how he has managed to get by, he answers, “I’ve considered Nyo dead since 1991. Dead people don’t miss their wives or kids. Otherwise, I would’ve gone mad.” To be a living dead – that is how he describes the current Japanese system of refugee recognition has made him feel. He is not the only one who has suffered from the prolonged exceedingly limited rights and freedom by being on karihoumen indefinitely. 4,671 people were on karihoumen at the end of 2022, many of whom are asylum seekers who have lost their right to stay in the country after having been rejected for their refugee recognition application. In Nyo’s eyes, many refugees are being abandoned in this in-between state of not legal but not quite illegal either, barely given any basic human rights.

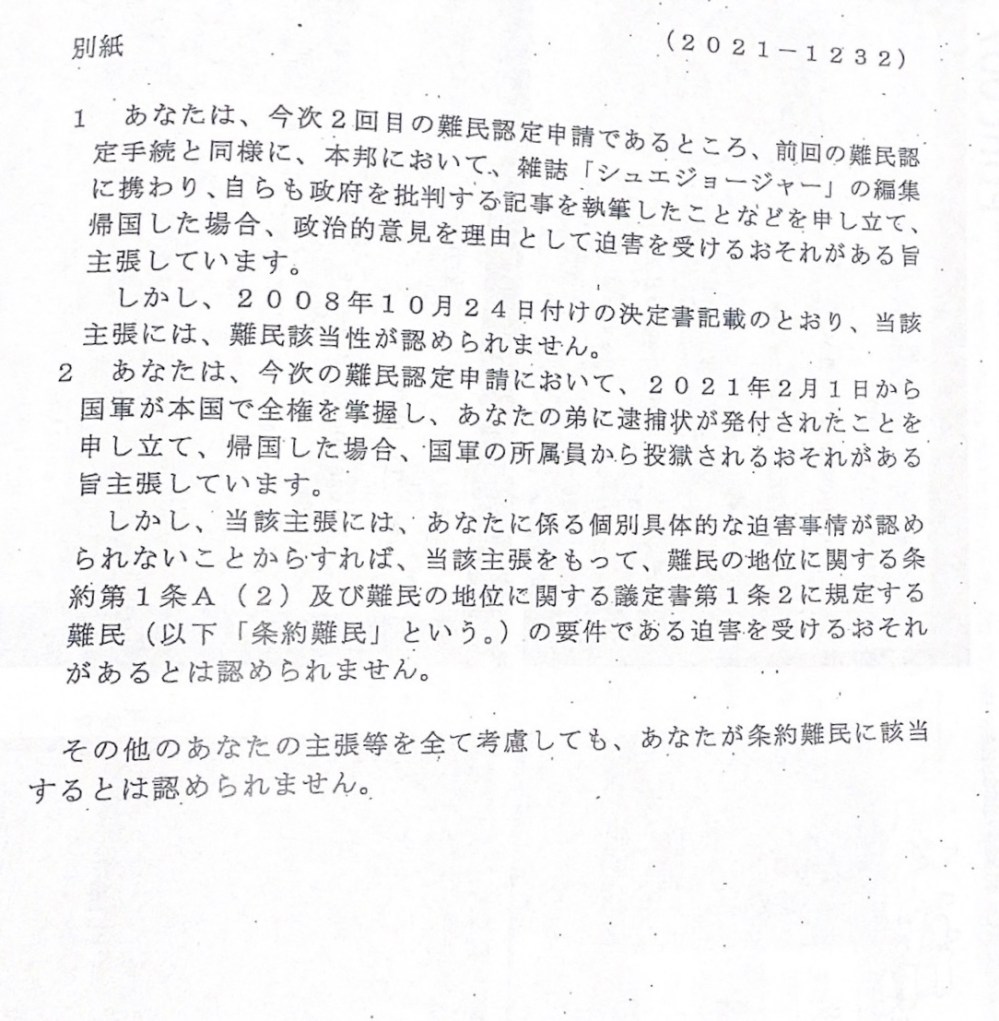

In July 2022, he received the result of his second application for refugee recognition. Much to his disappointment, he was rejected again. However, this time, he was finally given a visa that allowed him to stay and work in the country. Now, thanks to this visa, Nyo can pursue his studies or seek employment support from Hello Work, a government-run organization supporting employment for those who are struggling. Although he is certainly happy with the rights he was finally given, he cannot help but wonder how his life could have been better if this support existed 30 years ago from now. Even for those with legal status or refugee recognition, there are limited job opportunities and it can be challenging to break out of the vulnerable situation, especially with the lack of policies that accommodate non-Japanese citizens.

“I can study now because of Hello Work. Don’t you think it could have been better if it existed 30 years ago?”

2.2. Discriminated Refugees

While he struggled for over a decade to receive his visa, Japan accepted thousands of refugees from Ukraine fleeing the Russian invasion, promptly granting them the right to enter and stay. Nyo makes it clear that he does not have any negative feelings toward Ukrainians, as he understands their struggle of experiencing violent moments. Nevertheless, he points out the different treatment for the Burmese people, also fleeing the violent crackdown that followed the coup d’état in 2021.

To illustrate the difference in the acceptance of the Burmese and Ukrainian refugees in Japan, he first compares the visas they received. While the visa he was given after years of going through the procedures was only valid for six months and with a limit of 28 hours per week of work, the visas given immediately to Ukrainians were valid for a year and with an unrestricted work permit. Even now, Burmese refugees are required to meet certain conditions, such as having reached the end of their current visa or not being able to do so for a reason that is out of their control, to be given the same visa as their Ukrainian counterparts. Nyo was already in Japan when the coup happened in Myanmar in 2021. Nevertheless, that is not to say he is not fleeing the danger that is imposed on his home country; not being able to or even not willing to return due to the fear of safety is the fundamental element in the definition of a refugee. Having experienced a traumatic and oppressive life that is happening again in Myanmar, he believes that he should also be allowed to enjoy the same rights and freedom as Ukrainian refugees.

2.3. “Fake” Refugees

Nyo points out another underlying issue with Japanese immigration: the refusal to accept labor immigration. Back in the 1990s, at the height and the fall of the bubble economy, the labor shortage created a dependence on unofficial foreign workers. Nyo himself was one; he found a job shortly after his arrival to the country as a tourist in 1991, where he was hired to replace an 82-year-old man and the only thing they did was to make a copy of his passport. Recognized as a hard, good worker, Nyo kept working across departments in the company until he was detained by immigration in 2008.

Three decades later, the relevance of this situation remains. Nyo was not able to work for 14 years that he was on provisional release (karihoumen), but he says 99% of his fellow former detainees who are now on karihoumen are working despite the terms of the release, simply because “you cannot survive in Japan if you don’t work.” He further explains it is rare for such unofficial workers to be caught by police and that the employers turn a blind eye, using the Japanese saying “Uso mo hōben (嘘も方便)” – meaning that a lie is sometimes necessary, especially when the circumstance justifies the lie. “They need workers but they do not want to be held liable for knowingly hiring those who do not hold a working permit, so they pretend they don’t know,” he says. In fact, there have been cases where even the president of the company admitted to hiring a foreign worker knowing their lack of work permit due to a serious labor shortage.

In the discourse given to justify the low number and strict system of refugee acceptance by Japan, the term “fake refugees” often appears. It refers to the idea that there are individuals who apply for refugee recognition to enjoy the benefits even though they are not refugees. Particularly, the idea argues that some asylum seekers are economic migrants in disguise, “faking” as refugees as a way of obtaining work permits. The Japanese government has repeatedly issued a statement attributing the prolonged application review process and hindrance to protecting “genuine” refugees to the “abuse” of the system by the applicants “whose objective is to work” making claims “clearly unrelated” to being a refugee.

As Nyo points out, there is no “work visa” in Japan. Instead, visas given on the basis of work are specific to the type of work. There are currently 23 kinds given to varying but mostly skilled workers. Nyo argues that the so-called “fake refugees” only resort to applying for refugee recognition to work because there is no other way to work here legally. “Humans are animals too, so it is natural that we want to work in order to eat and to live,” Nyo says. In his view, “fake refugees” are thus created by the system that fails to acknowledge the labor shortage and provide an adequate framework for the tens of thousands of unofficial workers who have contributed to the society and economy of Japan.

The effect of the idea of “fake refugees” is tremendous. Asylum seekers such as Nyo, have faced more difficulty in getting their genuine claim to be recognized as refugees upheld due to this pre-conceived idea that a lot of the applicants are “fake.” A lot of them are then left in a precarious legal state that leaves them no choice but to seek work illegally to survive, which paradoxically feeds into the argument that they are “fake” refugees “whose objective is to work.”

3. 32 Years in Japan and Counting

Nyo has had a long journey of hardships. In his first 32 years in Myanmar, he witnessed the oppressive regime and feared for his safety when the hope for democracy brought by the 1988 Uprising was violently suppressed by the military junta which was to last the next 23 years. In his next 32 years in Japan where he fled to, seeking a life where he can support himself without risk to his physical and emotional well-being, he faced heavy restrictions on his everyday life and felt “neglected” by the government who has pledged to protect refugees like him.

Nevertheless, Nyo is happy with his decision to come to Japan. As a major reason, he lists the freedom of speech. Since soon after arriving in Japan, he has been passionate about compiling and spreading information through media for his fellow Burmese people in Japan. One of his early projects was a political magazine he frequently published with his friend. He would watch the Japanese news channel on TV, quickly jot down the key points in his notes, and translate the Japanese reports into Burmese with a dictionary ready in his hand. This was not an easy task for Nyo; his Japanese comprehension was limited, and printing hundreds of copies was expensive – “In 2001, it was costing more than 200,000 yen per month. I put all my monthly salary,” he remembers. However, he knew the value and importance of sharing information and considered it his duty to do so for the hard-working Burmese residents in Japan who did not speak Japanese or have spare time to catch up with news on TV.

“For my Burmese peers to understand information, I translate it into Burmese. In order to do so, I first had to understand the information myself. No matter what, it was a must for me to comprehend the full story.”

As social media emerged, he started using Facebook to carry on the task online. Compared with traditional media, including magazines that he would publish, he emphasizes just how rapidly information can be shared on social media. “When the Minister of Justice was fired, I posted it immediately. It was so effective,” he gives an example. Studying politics and circulating valuable information he saw on TV on social media is also what he thinks his “job” is in the movements against the military regime that took control after the 2021 coup. “I don’t know who, but I will be happy if my post could be useful,” he says.

“In Myanmar, no matter how smart you are or how famous a writer you become, you can’t write freely. I can’t do anything with my opinion in Myanmar. In Japan, I can. So I think it would be a waste if I didn’t use that opportunity.”

He has been taking part in this activity for 30 years. Indeed, Nyo himself likes to obtain new information and widen his knowledge. What was more important for him was “how” to better convey information to others and help them to be closer to events occurring in Japan. Reflecting on what he has disseminated in media or the criticism of the Japanese government he made while talking to us, he expresses what is great about living in Japan: “In Myanmar, we can’t speak freely, write freely, or publish magazines like mine. That’s fine in Japan. I think that’s my biggest lucky opportunity. I need to do in Japan what I can’t do in my country.” He clarifies writing only about the politics of Myanmar as an activist is not his goal. He says, instead, it is to learn and write about everything “because you can in Japan.”

Nyo has another dream or a mission that he sees for himself. “I want to build a temp agency for the Burmese orphans and teach them Japanese,” he describes. As he acutely sees the labor shortage and dependence on foreign workers in Japan, he believes many Japanese companies will expand their business in Myanmar when peace is brought again. He sees that there will be demand for Japanese-speaking Burmese workers then. “Even if it’s as simple as right or left, it would make a difference if drivers, who are responsible for the customers’ lives, could understand migi or hidari in Japanese,” he continues.

Having supported Burmese orphans in Japan for a long time, he believes this will be a perfect opportunity for such orphans who have no income. “The work that you would pay a Japanese worker 200,000 yen can be done by a Burmese worker for 70,000 yen in Myanmar. That will be heaven for the kids in the orphanage,” he explains the idea, referring again to the contribution of foreign workers to Japanese companies that he also experienced himself.

It was surely hard and challenging for him to start his new life here. However, instead of being concerned about his life hurdles, he always saw the positives in life and appreciated what he had around him. He is happy about how far he has come. “I do not regret coming here, this was my decision,” says Nyo. While he has clear ideas for continuing to spread information through media or teaching Burmese youth Japanese for more job opportunities, he explains he does not plan his future, referring to his Buddhist belief that no life is permanent. He says “I only think about doing my best for things that I have now,” which was the lesson he was taught from his father and the goal he has always set for himself. Citing another Japanese idiom “Inga ohou (因果応報),” Nyo firmly says he believes that the good he does will come back to him.